Archive for 2005

I’m borderline bored today. Read some of Sources of the Self but there’s too much talk of God. Read about how he thinks we may be in a watershed time (written though in the late 1980s) and spoke of how we have a hard time imagining old ideas like the divine right of kings. I’m at the point where I have a hard time imagining God ideas – although I remember faith, I’m working with a memory of an experience, which is different than actually feeling it as real today. It’s like my thoughts last week on myth – as something we’ve overcome, or something which served us and does no longer.I must say I’m particularly animated by the idea that I live in a complicated and technologically sophisticated civilisation. This is something Firefly helped bring to my awareness, through their contextualization of humans spread out across a new solar system, having packed up everything and moved it off world, where they felt free to begin the process of ecological destruction to build complicated early 21st Century cities all over again since there was now many worlds of resources at their disposal. And how Joss Whedon talked of wanting a show that was about ‘us’ – early 21st Century Americans (including Canadians) and revisiting the Western. And so you have a future five hundred years away in which everyone is using things we’re familiar with, like keyboards (no mysterious interfaces like on Star Trek and printed tee-shirts, and everything very familiar to us, as if we have in many ways plateaued, similarly to the way the candle and travel by horse was familiar to people across the centuries before the lightbulb.

So, the idea that I’m living in an emerging global civilization, which is so complex, but which enables me to do almost anything, I find interesting and exciting. To be here when it’s all new and fresh. And what this all means opposed to the Old World, and old world art and culture.

As an artist, I’ve struggled to find my voice and my place within the culture. I’ve also been caught up in the myopia of industry – to participate in the segregation, to go to openings, to party with fellow cultural workers, to read the poorly written and poorly thought documents, all the while not seeing the forest for the trees, and all the while looking in a rear-view mirror as it were: things from the past, and cultural movements better seen through hindsight. Getting lost in what it all means.

We are cut off in the end, from the experience of our lives, what it means to be alive now and to be comfortable with our selves. I sense a great trembling before uncertainty in this regard – the Buddhists who tell us we can be happy now and who want to enlighten us, wake us up to the wonder already here in our lives, but simply getting us to pay attention to our minds and our thinking – this is all seen with a sense of skepticism, but also, I think, there is a deep nostalgia for misery. So used to complaining and to being entertained through moving picture stories, we fear the length of our lives and the prospect of being bored.

Northrop Frye’s article on boredom vs. leisure summarizes the cultural wars I’ve witnessed in my still young life, and in the end lays it all on education … which broadens our perspectives to take in more than what the narrow view offers, the narrow view being by definition limited and quickly exhausted, so we find ourselves bored. The leisured, on the other hand, move through life being productive, pursuing their interests and by default contributing to society and civilization.

But what does any of this mean? What is it to contribute to humanity or civilization or to society? Those ideas were dissected by the post-structuralists which encouraged what Waggar called credicide, draining from our lives the sense of meaning which animated our imaginations and hence our lives – gave us that sense of certainty we seem to desire.

Perhaps our need for certainty is genetic, stemming from the days when uncertainty about yonder hill could get one eaten by a leopard. If that’s the case, we need a technology to deal with it. However, like our obesity problem, we’ve fallen victim to ancient biologies – comfort foods being comforting because of their fat content, which was very useful in scavenging days, but no longer. We now know this through science, and the concept of calories can help us control what we eat, in addition we know that to burn extra calories we need to exercise. But do we have similar knowledge to help us live with uncertainty? Is Buddhism such a technology?

The question is not one of who to make art for – fellow artists and further for collectors. But how to make something so that for the next thousand years, anyone (or at least, some) can see it or read it or whatever, and know that I was a human being just like they are, that I felt as they do sometimes, and in so doing, help bridge the gap of time, help them feel like they are part of the bigger story of civilization. So today, in 2005, I can read St. Augustine’ Confessions and recognize a fellow human being, and learn something of the context of those times. Again, people are still reading Tolstoy’s War & Peace which is set two hundred years ago, and in the process are learning a greater context.

If myth has died out in our age, one sees how that narrative culture we live in has replaced it. The past century was one resembling the wipe of a movie – the fade in or the fade out, how briefly the two images are combined in one still. The Old World of horses and carriages, inkwells and candles; of killing whales for oil, was replaced by a world where we dug oil out of the ground, to fuel our combustible engines for what was at first called a horseless carriage, and inkwells disappeared into speciality shops and art supply stores. Myth died and was replaced by the novel and movie, either projected in two to three hour stories on a large screen (replacing live theatre) or was divided up into half hour to an hour segments for the television machine of living rooms. Poetry, which was exulted for so long in so many cultures, disappeared too into specialty markets, replaced by the lyrics of pop music. Firefly suggests this new world will be with us for another five hundred years.

Picking up on the rear-view-mirror comment: one thinks of the side mirrors, and this past week I was trying to imagine what vision for a rabbit must be like, with it’s eyes on the side of it’s head, forward and backward in their periphery. How would their brains assemble the picture? Our eyes both face forward, overlapping, giving us and animals like us (apes and cats and so forth) binocular vision. I imagine something of what a rabbit experiences could be seen by placing two side view mirrors in front of us, at the angle so that we see the sweep behind, and are blinded near what we experience as front.

If hindsight then, is 20/20, one should further argue that this is the case for animals. The whole point of our lives since the beginning has seemed to be better than the animals. To be human is to see what’s in front of you clearly, and to be blind to what’s behind.

From my journal at the time, where I’d copied and translated it. From my Grade 10 French Class fifteen years ago, dated December 8 1990:

Where is Santa Claus?Where is Santa Claus? To discover the answer to this question, I set about asking children. I asked nearly fifteen children when one told me where he lived really!All the others has said that Santa lived in the North Pole, but after all these answers, one walked into my interview room.

He had big red shoes on his feet and green pants, with a big yellow shirt. He had black hair and big ears.

I asked him his name. ‘Nerwin Tisslefoot,’ he answered. Then he told me…

‘I heard you were asking kids where Santa Claus lived. I’m 7 years old and I know. All the other children think he lives at the North Pole, but it isn’t true. Santa Claus (his real name in Filbert) lives everywhere in the world. In the winter, he lives in Siberia, where he catches his reindeer.

‘There (the name of the place is Northpolliqr) is a huge post office, where Filbert receives the merchandise orders and money from parents all over the world, who buy all the toys from him. On the 20 of December, he puts these great big 767 engines on the feet of his reindeer, Prancer, Dancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Donner, Blitzen and Rudolph. And on Rudolph, he puts a big red flashlight on his nose. On the 21st of December, he takes off from Northpolliqr, and he flies all over the world, delivering his merchandise to the parents who bought it. He buys all the VCRs, televisions, and toys in Siberia, even if everybody thinks Siberia is poor, but that idea, that is propaganda. It is really rich like the States, or Canada.

‘Anyhow, Filbert is in North America on the 24th – every year straight, never misses – and on the 25th, he flies back to Siberia. He de-hitches the 767 engines, gives his reindeer over to an old lady who looks after them during the year, and he catches the next flight to China.

‘At the beginning of January, Filbert enters his Buddhist monastery, and becomes a Buddhist monk until April, then he goes to Iraq.

You know, in Iraq, it’s the Islam religion, and they celebrate the birthday of Muhammad, like we celebrate the birthday of Jesus Christ. And, like we give presents on Christ’s birthday, they give presents on Muhammad’s birthday. This year, Filbert gave Saddam Hussein Kuwait! That’s why Saddam doesn’t want to get out! He doesn’t want to give up his present!

‘After Filbert’s done in Iraq, he goes to Florida for the fall, to party down with the old timers down there.

‘After that, he’s in Siberia again, and the cycle begins anew. In fact, he’s there at this instant!’

Nerwin Tisslefoot finished his story. I said ‘Thank you Nerwin,’ and he left. I followed, wanting to go home, take about 20,000 aspirin for the migraine he’d given me, and go to bed.

Fini

The cultivation of the mind rather than cultivating the body

Yet there are many who do not cultivate either

So they are the ones who are told that so and so was gay, left handed, autistic, dyslexic – had whatever other condition

To make them ‘special’ so that you and I remain not special, when in reality, we cultivate neither our minds nor our bodies, and wallow in lumpen video game mediocrity, believing we cannot be taught, cannot achieve, and that one must be pathological in order to contribute.

There’s an interview with Slavoj Zizek from the Guardian which pretty much confirms my suspicions as to why I shouldn’t take him seriously – I first heard of him a couple of years ago through a friend who was briefly infatuated with his writing; then looking into it I found it unintelligible, and then further it became Lacan inspired nonsense, and now James Harkins has laid it all out for us, in an interview subtlety designed to impress those with my prejudices, which he perhaps shares.

My highlights:

A one-man heavy industry of cultural criticism, the 58-year-old Zizek has authored more than 50 books, which have been translated into more than 20 languages, on subjects as diverse as Hitchcock, Lenin, and the terrorist attacks of September 11. His brand of social theory – a peculiar amalgam of Karl Marx, the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan and the trash can of contemporary popular culture – has long afforded him a cult following among fashionable young academics.

Comment: Marx and Lacan are two examples of pseudo-science, and refering to the trash can of pop culture is to say that as trash perhaps it’s not something worth dealing with. Zizek appeals to ‘fashionable young’ academics – which is to say the naive, impressionable, and shallow. Would it not be true that to build arguments out of things not really worth considering is to build an argument itself not worth considering, the equivalent of fantasy?

If I were as fame hungry and vain as Zizek, I might want to start interpreting everything through the lens of Brothers Grimm fairy tales.

No longer tethered to a single institution, Zizek spends his time roving between speaking engagements at institutions all over the world. He is leaving London first thing tomorrow, he tells me, for Paris to be profiled by the newspaper Libèration. Then he is off to headline a Design Congress in Copenhagen (“??7,500,” he shouts to me, still under the photographer’s cosh, “first-class everything, and all that for 40 minutes selling them some old stuff”) and then it is back to Slovenia.

Comment: First class everything, eh? Not bad for a Revolutionary Marxist. The type that overthrows exploitative aristocracy to become aristocracy themselves. Some animals are more equal than others.

On April 1 this year (“a great day to get married”), he married a 27-year-old Argentinian former lingerie model and now spends one third of his time in Slovenia looking after his young son from a former marriage, a third of his time with his new wife in Buenos Aires, and the rest of his time on the road.

Comment: Here we have the degradation of men, especially of older men, who are represented as commitment phobic and chasing after women young enough to be their daughters. Here we have Zizek knocking up a ‘former lingerie model’ which is to say, she had nice tits and an exemplary body, and probably cannot converse at Zizek’s level when it comes to ideas. Zizek has a child from a former marriage, which is also to imply that the lingerie model is a home-wrecker. Zizek, being the ethical fellow we know him to be (“Come on,” he says. “I don’t have any problem violating my own insights in practice.”) could not resist the temptation offered by his new wife. In the end, one is left with thinking: what a fucking bastard.

And not to mention the whole thing about him resembling Jesus.

Geesus.

Northrop Frye, from The Educated Imagination (1962):

So you may ask, what is the use of studying a world of imagination where anything is possible and anything can be assumed, where there are no rights or wrongs and all arguments are equally good? One of the most obvious uses, I think, is its encouragement of tolerance. In the imagination our own beliefs are also only possibilities, but we can also see the possibilities in the beliefs of others. Bigots and fanatics seldom have any use for the arts, because they’re so preoccupied with their beliefs and actions that they can’t see them as also possibilities. It’s possible to go the other extreme, to be a dilettante so bemused by possibilities that one has no convictions or power to act at all. But such people are much less common than bigots, and in our world much less dangerous.

What produces the tolerance is the power of detachment in the imagination, where things are removed just out of reach of belief and action. Experience is nearly always commonplace; the present is not romantic in the way that the past is, and ideals and great visions have a way of becoming shoddy and squalid in practical life. Literature reverses this process. When experience is removed from us a bit, as the experience of the Napoleonic was is in Tolstoy’s War and Peace, there’s a tremendous increase of dignity and exhilaration. I mention Tolstoy because he’d be the last writer to try and glamorize the war itself, or pretend that its horror wasn’t horrible. There is an element of illusion even in War and Peace, but the illusion gives us a reality that isn’t in the actual experience of the war itself: the reality of proportion and perspective, of seeing what it’s all about, that only detachment can give. Literature helps to give us that detachment, and so do history and philosophy and science and everything else worth studying. But literature has something more to give peculiarly its own: something as absurd and impossible as the primitive magic is so closely resembles.

Earlier this year I had the misfortune of attending an abysmal presentation by a visiting academic at one of Toronto’s universities. Afterward, over drinks with my companion, we talked about my dislike for what we had experienced. I wasn’t too fond of the theorizing, having come to see psychoanalysts and their spawn (Lacan and his followers) as practitioners of a pseudo-science, and their theory disconnected from anything I’ve ever considered real. My friend spoke of refinement, that participating and discussing ideas at that level was form of distinction, and sophistication. Her arguments immediately made me think of this by John Ralston Saul, which I’d recently read. I think he convinced me when he threw in the bit about the shoes.

White Bread Post-modern urban individuals, who spend their days in offices , have taken to insisting that she or he is primarily a physical being equipped with the muscles of a work-horse and the clothes of a cowboy. The rejection of white bread in favor of loaves compacted with the sort of coarse, scarcely ground grains once consumed solely by the poor follows quite naturally.

White bread is the sophisticated product of a civilization taken to its ideological conclusion: essential goods originally limited by their use in daily life have been continually refined until all utility has been removed. Utility is vulgar. In this particular case, nutrition and fibre were the principal enemies of progress. With the disappearance of utility what remains is form, the highest quality of high civilizations.

And whenever form presides, it replaces ordinary content with logic and artifice. The North American loaf may be tasteless but remains eternally fresh thanks to the efficient use of chemicals. The French baguette turns into solidified sawdust within two hours of being baked, which creates the social excitement of having to eat it the moment it comes out of the oven. The Italians have introduced an intriguing mixture of tastes – hands towels on the inside and cardboard in the crust. The Spanish managed to give the impression of having replaced natural fibre with baked sand. There are dozens of other variations. The Greek. The Dutch. Even the world of international hotels has developed its own white roll.

In each case, to refine flour beyond utility is to become refined. This phenomenon is by no means limited to bread or even food. Our society is filled with success stories of high culture, from men’s ties to women’s shoes.

(From The Doubter’s Companion, 1994)

In his book on Northrop Frye1, Jonathan Hart describes Roland Barthes as attacking the myths of ‘the bourgeoisie’ and stating that for Barthes, the problem with what is often translated as ‘middle class’ was its inability to imagine the other. Thus, I go through artschool being informed and taught these Marxist ideas, and for a time immediately after graduating am prone to denounce middle-class values as bourgeois.

Then I read Steven Pinker’s account of the middle class (in The Blank Slate, p.416, in his chapter on art), which I had to agree with:

As for sneering at the boureoisie, it is a sophomoric grab at status with no claim to moral or political virtue. The fact is that the values of the middle class – personal responsilbilty, devotion to family and neighborhood, avoidance of macho violence, respect for liberal democracy – are good things, not bad things. Most of the world wants to join the bourgeoisie, and most artists are members of good standing who adopted a few bohemian affectations. Given the history of the 20th Century, the reluctance of the bourgeoisie to join mass utopian uprisings can hardly be held against them. And if they want to hang a painting of a red barn or a weeping clown above their couch, it’s none of our damn business.

The problem of imagining the other is still with us, but like everything has been updated to a new century’s context. ( I’m inclined to say it’s generational in one regard – my parents certainly have this problem, but my parents are also political and social conservatives).

The problem of imagining the other was clear to me in the article I read yesterday by Anthony Harrigan, called ‘History, the Past, and Inner Life’ (PDF) which seemed interesting at first but then became intolerable. He seems to argue that while in the past there has been a connection between a technically advanced society and barbaric behavior (the Nazis) he seems to imply that one cause the other, which is nonsense. He says this of the culture of the United States:

One has only to look at the ‘entertainment’ industry media in the United States. The technology of the electronic media is unparalleled in the world, but much of the comment is hostile to the values of our inherited civilization. The tide of pornography is rising, flooding the internet, exposing the average user to the most vile images.

Which was the first thing to make me suspicious. Then he goes on to write:

Dr. McClay has pointed out that an increasing number of academic historians strive to ‘demonstrate that all our inherited institutions, beliefs, conventions, and normative values are arbitrary ???social construction in the service of power???and therefore without legitimacy or authority.’

An argument to which I’m sympathetic, since I don’t have such a negative view of humanity to see them as all power greedy, preferring the Buddhist view that all beings desire happiness. His point though is raised in order to say the following:

We see this process at work in the effort to de-legitimize the institution of marriage established as a religiously ordained estate between a man and a woman. Judicial validation of ‘civil unions’ between homosexuals undermines the most fundamental institution of our society, monogamous marriage. It opens the door to polygamy and every sort of perverted sexual activity, including bestiality.

Which is of course bullshit, and our first clear example of this fellow being unable to imagine the other. And yet, when reading this yesterday, Marxist terms filtered through French semiology did not pop into my mind; instead I had the realization that I was reading the right-wing point of view.

One reads on, to find this gem of intolerance (the emphasis within is mine):

In this era in which leftist social doctrines prevail, it isn???t surprising that great emphasis is placed on multiculturalism in schools and colleges. The aim in promoting multiculturalism is to downgrade or disavow the culture of our nation and civilization. In many educational institutions, for instance, students are launched into the culture of India before they study the culture of the United States and the Western world. This is a deliberate process designed to underscore the point that our American and Western history and values do not have primacy. Multiculturalism leaves those exposed to it morally disoriented and rootless. Students are supposed to learn that there is nothing special about our traditions; no one is to regard them as having authority in life. A mishmash of culture is ladled out so that young people are without authoritative guidance in adopting values. Those who want to downgrade our traditions and values have what the writer Joan Didion has referred to as ???preferred narratives.??? These narratives have as their central theme that the United States has an oppressive society and has been that way from the start. They regard the Constitution of the United States as a conspiracy against the powerless. They choose to depict minorities as victims regardless of the particular circumstances.

Here I see the power of freedom of speech and thought, to be able to read something I find offensive but which gives me a privileged glismpe into answering the question we express nowadays with ‘WTF?’

What the fuck they are thinking is that multiculturalism is to degrade one’s own culture? How about the idea that we take our congenital cultures for granted – that we don’t need to appreciate them since we are living within it, and see The Other as offering us different perspectives. One thing that Mr. Harrigan does throughout is to talk of ‘our culture, and our civilization’, dividing the world into haves and have nots, closing the door to ‘guests’ in a sense. One detects a distinctive lack of welcome in his use of words.

How does one claim a culture with such certainty? And I think it needs to be asked, why should anyone be so proud of the parochial, patriarchal American culture, so sure of itself, that it doesn’t require the perspectives of other experiences? As Kurt Vonnegut brought up in his recent appearance on The Daily Show in a sarcastic defense of the situation in Iraq, a new democracy takes 100 years to free its slaves, and 150 years to give women the vote, and that at the beginning of democracy, quite a bit of genocide and ethnic cleansing is quite ok.

Why is it about the Right that seems to require this sense of certainty? The argument here seems to be that Mr. Harrigan is so weak-minded that being exposed to the Kama Sutra will cause him to indulge in hedonistic pleasures of which he never dreamed, instead of simply saying, ‘that’s not for me’? You encounter this weak-mindedness with their talk on God and morality – that without God existing, there’d be no reason for moral rules, and than what do you do? How about continue to treat others well because, as it’s been said by many a previous Christian, ‘a good deed is its own reward’?

My ultimate point here though is to say that talk of ‘the bourgeoisie’ is outdated, and that to be able to make the same points being made 50 years ago by the likes of Roland Barthes, one talks of ‘the right wing’ or ‘conservatives’. Which is a little unfortunate – a conservative streak in society that builds museums, ‘to conserve’ is welcome and necessary, but one that fails to imagine other cultures and appreciate their differences and the perspectives those differences offer is simply toxic.

1. Northrop Frye: The Theoretical Imagination ISBN 0415075378

So, according to my sister’s boyfriend, who witnessed it, there was a nude jumper this morning on the DVP. He jumped off one of the overpasses near the BMW facility (either Queen St or Eastern Ave). Of course, they didn’t bother to tell us that on the evening news. Instead, Global gave us a report of increased cycle-cops around schools to intimidate the 16 year old out on bail (whose face was graciously blurred).

Now, I understand that there’s something like at least one suicide a week on the TTC, but they don’t want to make the actual numbers public. It would seem they prefer the accuracy of innuendo and rumour. The same is true for people like this morning’s fellow, who (if successful) chose to leave the earth as buck naked as when he arrived. I’ll credit him with some performance art originality.

But why the silence? Why do news editors everywhere think we should care about the car wrecks and murders? I haven’t been murdered lately, I don’t plan to be anytime soon. But what business is it of yours if I am? The same goes for the car accident. If anything, that’ll be between the insurance companies. I’ll concede it’s everyone’s business inasmuch as it ties up traffic, but beyond that I don’t want or need to know. Isn’t it true that murders are rarely random, but usually are the culmination of some dispute?

We may live in a time when Dr. Phil thinks the whole of the United States and Canada needs to witness the tawdry details of some family’s anguish (today’s episode on incest for christ’s sakes) which completely disregards the reasons for confidentially in the first place.

Let’s be clear here: there are some things of which it is none of our business. I don’t want to know the problems of some abused family, unless I’m in the position of needing to help. But I’m not a priest, a counselor, a psychiatric worker, a bail officer, etc. And if I was, I’d be under strict gag laws. Confidentiality exists as much for the benefit of society as it does for the relevant parties. I for one felt I didn’t need to know the details of Dr. Phil’s incestuous family, and quickly changed the channel in disgust. (For those of you who advertise during his time slot, why not start sending that money to the Red Cross?)

The arrest of the local pedophile, the murder of an abused wife, or the coke habit of the local hoodlum, the grow-op of our neighbors … all this is brought out to be part of the public record. This news is supposed to do what? If anything, it makes us feel less safe, but Toronto remains one of the safest cities in the world, and what crime exists just seems part of life. And given that seems a large portion of this crime is all drug related, it makes me think the only reason we keep our stupid drug laws in place is to ensure the police job security.

Anyway, I for one want to know how many people think Toronto is too awful to live in. I would like to have some understanding of the suicide rate. Because all the regular crime gets reported, I’m able to sit here and think it’s relatively low, compared with other places. I get to formulate what understanding I bring to the issue, and feel rather safe in the metropolis. But I can’t say the same for the depressed, the scared, the anguished, the people who need help but haven’t gotten it, for those for whom society has failed.

I’m reminded of Charles Taylor‘s thoughts now. Taylor, a philosopher originally from McGill (and doing the scholar circuit the last few years – he was at U of T a year ago) argues that while the Modernist philosophical tradition begins with Descartes’ introspection, our reality is really one comprised of dialogue. You might think that you are, but Decartes began the line of telling the rest of us. You cannot exist alone. Our lives are comprised of conversations, and even this writing is part of a conversation frozen into our alphabet’s symbols. The comments section below are there for your side, your contribution.

It is because we are social creatures that the news exists – all these reporters on the street talking to some box on someone’s shoulder would be absurd if they didn’t see themselves are part of a larger stream involving the unanimous and anonymous audience. They talk and therefore they are.

And as social creatures, we want to understand our place in society, so we have a tendency to gossip. So the news thinks we might be interested in the painful stories of people who can’t get along, and instead of being useful and warning us that there’s some psycho out there, instead we only get the news after they’ve been arrested (and hence, this is why I don’t really care about this type of news, it always comes after the crimes have been committed in the first place).

But suicides are a death built around the Cartesian model of introspection. I think I’m depressed and therefore I am. I think I can’t go on and therefore I can’t. They represent failures of our society to reach out the necessary hand, to bring someone into a relationship, to involve someone in a dialogue. Murders are crimes of passion, they involve at least two people, one of which is cruel. A suicide is an act of loneliness, involving only one person, whom people in general don’t care enough about. We extend our hard heartedness to not even mentioning their deaths on the news.

Is it because it’s shameful to kill oneself? Is it a left-over from Christianity, when suicides wouldn’t even be given a funeral? Is the TTC’s reluctance to talk about the people who kill themselves on its tracks because they think it’s morbid? The same must be said for the Go Trains, who regularly have ‘accidents’ involving pedestrians. With such a rate of ‘accidents’ that they show, it’s a wonder they haven’t been shut down has a safety hazard.

Morbidity doesn’t usually stop the news – how much more morbid is it to show us pictures of blown up buses in Israel? I clipped a few over the past couple of years, fascinated in that morbid way by the scenes of bodies frozen in death.

And even over the past week, with the catastrophe in New Orleans, the news is showing us anonymous rotting black bodies, which bring a grunt of awfulness from me, but also help me understand just how bad things are down there.

My point here is that the news has no problem feeding morbid curiosity. So why not go that step further and tell us about suicides?

Regarding the argument of selfishness and shame – when Kurt Cobain killed himself, all the fans were like, ‘what an asshole’ and bitched about his selfishness. That always seemed stupid to me. Are you saying then, that your selfishness is such that you’d prefer he stuck around suffering just so that you can go on buying Nirvana CDs? That was my argument at the time.

It’s not shameful to kill oneself. It’s an act of desperation, or if you’re a terrorist, of idiocy. If you’re so past caring about this world to want to live in it, what do you care about shame? And why should we as a society, continue to take their actions personally?

If you’re of the school that it’s a condemnation of our company, then I suppose I can see where you’re coming from, but I’d like to think we’re bigger than denying them identity out of a petty sense of insult. I mean, our world is pretty screwed up, and those that leave it voluntarily are probably saving themselves a lot of grief. But at the same time, I’d like to understand their motivations, their criticisms, in order to help improve the situation.

The news wants us to believe we live in a cruel world, full of crime and the winners of sports where one person or group defeats another in glorious competition. By denying us the reports of the losers, who validate its cruelty, they aren’t allowing us the chance to think about what’s wrong with the picture, and how it could change.

To the naked jumper: rest in peace wherever you are.

image: from Wikipedia

From this:

“The criticism is all the sharper because the President did nothing to alter his holiday schedule for 48 hours. Vice-President Dick Cheney remains on holiday in Wyoming. Condoleezza Rice, the Secretary of State, returned to Washington after being seen shopping for $7,000 shoes in Manhattan as New Orleans went under.”

Reminds me of another callous bitch who once suggested they should just eat cake. For fucks sakes, I’m glad these s-o-b’s aren’t my government.

I spent a week in Maine at the end of July, mostly reading fat books but every now and then giving my mind a rest with some channel surfing. The impression I got from my sampling of pure American television was that their reputation for being not to bright seemed well deserved. In that broadcast environment, even PBS looked dopey. I found myself really missing TVO and the CBC.

But, having come to see how great the CBC is, and how important it is to our television recipes, I can’t say I very much care about the current lockout. Because it’s been August, and I see it as part of the vacation – the usual cancon channels on radio and TV are whacked and so what? I can handle it. It’ll be over eventually. In addition, I do have lots of books to read and TV is mostly a waste of time, especially in the summer. I also have a new gig which means I’m not doing my regular home-office hours anymore, with CBC Newsworld on it the kitchen to give me something to listen to – I’m out and about and ignoring daytime TV.

Perhaps I’m just not facing the reality that it could go on and on like that hockey thing. I hear though that it could go on for at least 7 weeks – oh well. I mean, Peter Mansbridge didn’t get to fly to New Orleans to report from the scene, and who really cares? (Wasn’t it kind of disturbing the way all the reporters took the Boxing Day tsunami as an excuse to get out of the frigid continent for a few days … ?) I’ve had CNN on the past couple of days for those hours when I am ‘in the office’ because I have to orient myself to the reality that Louisiana now has more in common with Bangladesh than it does Ontario. Disasters do have a certain fascination and inspire a kind of awe, but it almost seems a good thing that I’m not getting a Canadian perspective on this story.

Anyway, with that nod to current events out of the way, I want to talk about the bigger picture of this CBC dispute. I think I dreamt about it last night, having some conversation about it, where I said that it being a lockout means that the CBC in effect fired their entire staff. In the first week, lots of people joked that the CBC is actually better now than the big egos have been temporarily put out to sidewalk. This sort of division in power – management versus the personalities and support staff, suggests the CBC is a creature with two heads and can function just fine with one. That’s a little disconcerting since it suggests massive and expensive redundancy. But redundancy is a good thing, so that’s not really worth complaining about nor should it be eliminated.

Let’s say this then: we are less than 6 months away from 2006, when we will undoubtedly be living ‘in the future’. The past six years have had a sort of legendary character -first we ‘partied like it was 1999’, than we were living ‘in the year 2000’ and then we re-watched Stanley Kubrick’s ‘2001’, enjoyed the palindromic character of 2002, and the past three years, (’03, ’04, ’05) have still seemed like an extension of the 1990s.

But now, everything is beginning to be different. While the belief amongst marketers is that ‘one should never launch a new product in August’ this past month has laid the foundations for the next ten to twenty years of common perception (at least in Canada) – a time frame which makes up the first quarter of the 21st Century.

The American nightly newscasters are all gone (Rather, Brokaw, Jennings), there’ve now been two natural disasters which remind us of our impotence in the face of natural forces, and Hollywood ain’t what it used to be, as the summer receipts show. Michael Ignatieff has gone from being an esoteric academic to being touted as the next Prime Minister (returning from Harvard to take up a post at U of T) – and if pigs fly in the next five years and that comes to pass, he’ll do so under Governor General Michaelle Jean. And the CBC has had a labour disruption, which threatens the broadcast schedule of new season of an updated version of hockey.

Like the guns of August 1914, it seems easy enough to ignore these developments at the moment, not yet conscious of the bigger picture, but let’s consider the following:

René Lévesque used to be a CBC personality in Quebec in the 1950s, until the 1959 68 day (two month) strike. The fact that the French CBC strike was allowed to go for so long embittered Lévesque toward Ottawa. He later said something to the effect that the English CBC would not have been allowed a two-month strike, and would have been forced to and end much sooner. The lengthy disruption in Quebec, in his opinion, showed how little English-dominated Ottawa cared about what happened in la belle province. And so Levesque went into politics ….

(As it is, only Jack Layton is demanding an immediate return of Parliament, and that’s to deal with this softwood-lumber, death of NAFTA thing. All those anti-globalization protests of the late 90s now seem like so much, ‘we told you so’. Ottawa clearly does not yet care about the CBC. Nor do I as I’ve mentioned do I – I mean, does anybody miss George Stroumboulopoulos’s show? … I can’t even remember what it’s called as I type this. So much for their efforts to win over my demographic).

So, point one – this lockout might have significant consequences. And in one way, it already has, since it’s forced podcasting to a new level. I’m not really on the podcasting bandwagon – I find it all rather pretentious. Everyone faking up a radio-like sounding thing and treating it as this new and great thing, and it’s only a trendy way to talk about an mp3 file, which have been around for what, eight years now?

I guess the difference is that mp3s have tipped past bootleg music because almost everyone in an urban core seems to have a fairly sophisticated computer and a high speed connection (and if they have a job they can afford an iPod to listen to their mp3 collection with).

You have radio stations like 102.1 CFNY The Edge offering Allan Cross’s The Ongoing History of New Music podcasts, and no, they aren’t the archived shows (which would be awesome), but some 1 minute clip, effectively acting as teaser advertising for the radio show. That is not worth a trend. Jumping on a downloading bandwagon and offering your readers/listeners irrelevant shit I find tries my patience – especially since one had to wait for the download to complete before being disappointed.

Via Tod Maffin’s site, cbcunplugged.com, we get to listen to phone messages. Oh boy. Nevertheless, this cat is out of the bag. While the content is rather lame, I’m excited by the fact that the employs have embraced the possibilities of this type of broadcasting. The upcoming CBC Unlocked will be something worth checking out.

It shows creative thinking that the management seems to lack, and it also seems like the type of thing which is allowed to happen because it’s unfiltered by office politics and bureaucracy and the like. Whatever happens at the CBC after this is all over, I hope they bring this back the mother corp.

(Which raises another thing: according to iTunes, the CBC3 podcast is number 1 in terms of popularity. It seems to be unaffected by the labour dispute. Why?)

Last week I listened to a couple of mp3 files from Australian radio of my favorite thinker, Mr. John R. Saul. He was on he tour promoting his globalization book, and he brought up his point that the economics of the past 25 years reminds him of 18th Century mercantilism. And so perhaps it follows that the bloging reminds me of the type of pamphleteering that helped spark the American and French Revolution. In those days, you wrote something, you went to a printer, and it was on the street in an hour. In the two centuries since, the middlemen of editors and marketers filled the offices of the publishing houses until reject letters became a writer’s rite of passage.

In his previous books, Saul likened the explosion of instant publishing in the 18th Century with a trend where a public of common people began trying to make themselves heard over the dominant voice of those in power. Post-modernism, inasmuch as it was the academic expression of trying to express what had remained unexpressed (because it had been put down by a dominant voice, in this case, the Modernist aesthetic and philosophical ideology) is nothing more than the first wave of people expressing themselves to those in power. (Ironic then how pomo has become noxious power itself). First radio and then television gave voice to the whole other segment of society which had been discriminated against by those who thought they were better than average. Jerry Springer’s infamous show isn’t so much a parade of ‘trash’ as it is a reminder of human variety, and especially of the need for adequate social and education programs.

Blogs and podcasting are continuations of this trend. As Saul wrote it, when things get too literary and language becomes too controlled by certain experts (whether post-modernist writers who can’t string a proper sentence together, or the rise in corporate ways of speaking so that every idea becomes inarticulate) there is a backlash, a corresponding balancing rise in the speech of everyday.

Humans are creatures of sound – and it is only with training that we become creatures of print. The rhythms of everyday speech will always seem more natural and be more effective at communicating than any purple prose from some show-off snob.

So I think blogs are great for that since their style is one that lends itself to being written as if it were spoken. I certainly think this way when I write – I’m confident enough in my ability to write well that I see no need to show off and am thankful to avoid the embarrassment of academic writing.

And now that a medium has come along which allows both text and voice files to be easily broadcast – we’re witnessing some kind of media utopia, and I remind you that utopia means ‘no place’ and the internet certainly has no place, and like the universe, having no centre, it is everywhere. Naming his perfect place utopia was a way of Thomas More to say that perfection is impossible, but perhaps that is true only when talking about material, human things, and not immaterial shadows of electricity.

For now we have a medium by which a locked-out staff at a national broadcaster can continue writing and speaking, and we now choose to download it and listen to it when we want. We are no longer forced to wait until their re-broadcast time or pay $20 if we want to hear it again. For one thing it’s shameful that the CBC last year stopped providing mp3 files of their shows; let’s hope this populism amongst their worker bees will break their outdated media models once and for all once everything gets back to normal.

And so, the last four months of the mid-decade year will be interesting times, as we watch a new status quo begin to develop. While the CBC lockout seems insignificant, it is part of a bigger picture that includes new hockey, new politics, new ways of speaking and listening to the masses, and new disasters that remind us of bigger pictures and long-term consequences. Whether or not the egos at the CBC return to their soapboxes anytime soon, our lives are way more interesting going into this autumn than they were a year ago. Hollywood may be complaining about a summer slump, and no wonder. It’s far more entertaining and engaging to simply pay attention to events.

Signs of the Times: the CBC lockout, podcasting, and the future

I spent a week in Maine at the end of July, mostly reading fat books but breaking from that with some channel surfing now and then. The impression I got from my sampling of pure American television was that it is no wonder the Americans are seen to be stupid all over the world (even PBS looked dopey) and that I really missed both TVO and the CBC.

But, having come to see how great the CBC is, and how important it is to our television recipes, I can’t say I very much care about the current lockout. Because it’s August, and I see it as part of the vacation – the usual channels on radio and TV are whacked and so what? I can handle it. It’ll be over eventually.

I guess I’m just not facing the reality that it could go on and on like that hockey thing. Something has told me from the start that it has a 3 week timeline. This is week two – there’s another week to go and then I’ll get annoyed.

It’s been a while since I posted … been a busy summer and such. And my art grumpiness has reached the level of ‘why bother?’ and so I’ve avoided a lot of shows in favour of reading biographies of Goethe. But on Friday night, I went out to the opening at Zsa Zsa, since it was the last show there ever.

After seven years, Andrew Harwood is giving up his gallery and moving out of the back. Zsa Zsa has been both a home and a business, but the business side never dominated his commitment to giving people an opportunity to show. In the past, he’s advertised the gallery as showing ‘the best and the worst of Toronto’ which brought a laugh out of me, since my show there in February of 2003 followed what I thought was something abysmal. As a rental gallery, Zsa Zsa was one of those open venues by which people could seek immediate reaction and criticism from an audience – and if anything sold, Andrew didn’t take a cut.

Harwood took over the space from Myfanwy Ashmore, Shannon Cochrane, and Keith Manship who pre-Zsa Zsa called the space the In/Attendant Gallery. Now, with Harwood’s departure, Paul Petro is taking over the space and so-far is planning on using it to exhibit some of his multiple collection.

For the final month, Andrew put together a couple of shows, the first of which opened on August 5th, and was dedicated to the theme of pot. I was away for that one but I heard it was quite a party, with 300+ people showing up. The second show opened last Friday night, dedicated to magic, or as Harwood wrote in his PR: ‘[it] is a simple show that celebrates the sweet magic of being lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time with the right people. This show lauds those folks and that place. Sweetness, magic and light’. Featuring Christina Zeidler, R.M. Vaughan, Will Munro, Maryanne Barkhouse, Fastwürms, Allyson Mitchell, Michael Belmore and Andrew Harwood, Bedknobs & Broomsticks is a nice little show which seemed to open on the right day – with that days thunderstorms reeking havoc across the city, the magic and withcraftery fit right in.

Now, there’s something going on in this city with regard to knitted wool. And in the way that strands of wool can come together to form a blanket or a sweater via a network, there is a network of relationships operating on those two blocks and expressing itself in the material of which sweaters are made of.

Andrew is one of Paul Petro’s artists, as are Will Munro, Allyson Mitchell, and Fastwurms. So it makes since that these artists are in this final show, as much as it does that it is Petro who is taking over the space. In as much as the artist community of Toronto is fractal – that is, divided up into ever smaller communities until only power couples and those with an overdose of self-esteem are left – the community in which Harwood finds himself is one that has been actively working out an ‘afghan aesthetic’ over the past couple of years. Allyson Mitchell and Will Munro have both used appropriated afghan blankets in their recent work, and while Cecilia Berkovic is not one of Petro’s artists, she has brought this to her work with Instant Coffee and especially to the room she designed for the Gladstone Hotel (viewable here).

Allyson Mitchell’s piece in this show is one of her collaged images based on shag carpeting, in this case that of a sasquatch terrorizing something. My conversation with her that night got into my recent trip to my hometown in Nova Scotia. I was telling her about how one of my friends there had a stuffed bear head on his wall, and from there we talked about taxidermy, as her piece uses taxidermy glass eyes and a bear nose.

Will Munro has a wonderful piece which I really liked, consisting of four axes tied together with loops of coloured yarn, using a 70s colour scheme of orange and brown. While axes are supposed to be dangerous objects, their shiny newness and their interaction with the yarn make this piece seem pleasurable and safe. This wool based aesthetic I find really comforting in a way, and given that it’s presence in this show follows the show dedicated to pot, I’m reminded of what someone once told me about what it feels like to be high – ‘you know when you’re a kid and you get up early on a Sunday morning, and it’s chilly, and you come downstairs and wrap yourself in an nice blanket, and how cozy that is? That’s what it feels like to be high’. Yes, comfort and coziness are as associated in my mind with afghan blankets as they were in my stoner friend’s, and thus I welcome this development in the Toronto scene, and it’s reflection in this last show at a gallery which helped foster it’s development through friendships.

But not all the pieces reflect the afghan school. The space is dominated by Maryanne Barkhouse’s piece, which many people thought was a dance floor, and asked if they could step on it. Consisting of a grid of images within a metal frame, and standing up about 6 inches from the floor, the images tell a beaver’s story.

RM Vaughan’s video continues in his theme (present at least in his video works) of self-disappointment. This time, he’s speaking of his belief that 40 year old gay men do not have mid-life crisis’s – rather, they go on tourist vacations, to tourist landmarks like the Eiffel Tower or the Pyramids. Richard is best known as a writer, and as such his monologue, playing through the headphones attached to the monitor, is worth listening to – which I write since so often I at least would rather not put headphones on to watch a video.

The window is dominated by the work of the Fastwürms – mushrooms and fake cakes, it is one of the most ‘magical’ pieces of all. The Wurms (which I’m supposed to write FASTWÜRMS -all caps with an umlaut) work consists of what they have called at various times ‘witch drag’ and so this piece and some of the others in the show fit in with this stream of work. While I don’t share the FASTWÜRMS’ love of witchcraft and magic, I do appreciate there work an awful lot, since they’re an example that something finely made and considered is always more interesting than some kind of crap that tries to get away with the heroics of ‘I can do that with my eyes closed’ sloppiness which artists glorify with the term ‘loose’. While virtuosity has its place, so does craftsmanship, and Fastwürms’ finely made things are force me to pay attention to take what they’re doing seriously.

Anyway, this last ever show closes to walk-ins on the 28th, but can be still seen by appointment until the 30th (which would require a phone call to 416-537-3814).

Bedknobs & Broomsticks

Until August 30th at

Zsa Zsa Gallery

962 Queen Street West

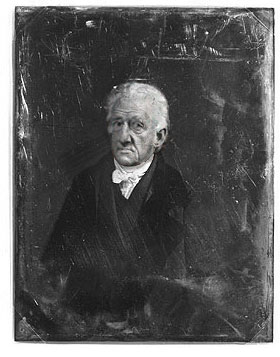

During the summer I’ve been reading up on Johann von Goethe. Somewhere someone noted that when Goethe died the first photographs had been taken, but this having happened in 1832, he never had a chance to sit for a portrait. Nevertheless, I tried to imagine his features (known from drawings and paintings and widely available via the web) in the grayscale of a 19th Century photograph.

Given that with a computer one can do almost anything, last night I sat down to see if I could make something. Imagine then that photography had been invented 20 years earlier, and that the famous Johann Wolfgang von Goethe had sat for a portrait in 1828. Of the two images I worked on last night, this one is the most successful.

Subject:London Terror

From: Timothy Comeau

Date: Thu, 21 Jul 2005 12:24:29 -0400

To: today@cbc.ca

Admittedly, as soon as I heard about this on this morning’s radio I turned on the television to, for lack of a better phrase, ‘witness the spectacle’. Given how two weeks ago you (CBC) suddenly dropped the Karla Homolka story in favor of a full day’s coverage to the events, and how you seem about to be doing the same thing today, it occurs to me that you are complicit in the terrorism by giving these jerks all the attention they want. Would they be so quick to set off bombs and kill and maim if they knew the media would ignore it in favour of Tom Cruise’s love-struck antics? I saw on the ticker that 15 people died in Iraq today, but you’re quite comfortable in burying that story. Breaking News story spectacles are part of the problem, and are never informative. Why not wait until you can actually inform me of something, and give me news I can use, not water cooler gossip?

Timothy Comeau

Craig Francis Power has written me a couple of letters from St. John’s, the latest deals with the latest controversy with The Rooms and Gordon Laurin’s firing.

Now, while the news channels today are creaming themselves about being able to devote another full day to the crumbs fed to them by the London police, we should remember that in the long run, visual culture and literature is where a society’s memory lies, and certainly not at the news desks of CBC and CNN, where, they tell us that today’s bombing occurred two weeks after the first round. No shit. I wasn’t born yesterday.

Goodreads began partially because of what I read by John Taylor Gatto in an autumn issue of Harper’s magazine a couple of years back:

After a long life, and thirty years in the public school trenches, I’ve concluded that genius is as common as dirt. We suppress our genius only because we haven’t yet figured out how to manage a population of educated men and women. The solution, I think, is simple and glorious. Let them manage themselves.

And that stayed with me. Then, last winter’s readings of John Ralston Saul drove the point home:

“There is no reason to believe that large parts of any population wish to reject learning or those who are learned. People want the best for their society and themselves. The extent to which a populace falls back on superstition or violence can be traced to the ignorance in which their elites have managed to keep them, the ill-treatment they have suffered and the despair into which a combination of ignorance and suffering have driven them. […] It’s not that everyone must understand everything; but those who are not experts must see that they are being dealt with openly and honestly; that they are part of the process of an integrated civilization. They will understand and participate to the best of their ability. If excluded they will treat the elites with an equal contempt”.

London Bombings

Bombers in London are suffering from a lack of imagination, by which they can’t relate to society at large. I’m reminded of something Mark Kingwell wrote ten years ago discussing crime statistics in the U.S. and noting that for some the conditions of poverty were so severe that going to jail was a step up, guaranteeing shelter and three meals a day. (Such motivations have also led many people into the military over the past couple of centuries as well).

One then begins to see that these suicide bombers are trying to escape their lives. And, as the media would like us to think – they all appear normal, aren’t in dire poverty. They always come across as a middle-class, albeit in some cases, lower middle class. Instead, we have a situation analogous to the suicides of Canada’s north, where the Inuit children, after years of sniffing gasoline for cheap and brain-destructive highs, are hanging or shooting themselves. We have a pretty good idea as to why those kids are self-destructive, and that is because ‘they have no culture’, the story being that the misguided intentions of a century ago to assimilate the native populations did terrible damage to their sense of self as a culture, and in effect, destroyed their imaginations. The imagination of themselves and their place in the world, in the grand scheme of things.

And so, I want to say that suicide bombers are suffering from a lack of imagination. That they are choosing to die, and to escape into the paradisiacal world (the only thing, one imagines, that has preoccupied their imagination for years) rather than continuing to live their dreary, industrialized, modernist, post-modernist, (or whatever other name we throw at it) lives.

Those of us who despise reality television and other aspects of pop culture choose do so because we feel that we have better things to occupy our imagination – great books, the art of contemporary galleries – ‘cinema’ as opposed to Hollywood blockbusters…. but if you’re a child of immigrants, and don’t identify either with your parents or fully with your peers, and instead your imagination is stimulated by religion …. it doesn’t seem to be so mysterious now does it, why these kids would do what they do.

We imagine ourselves, develop ambitions, or at least have plans for the future – next vacation and so forth. Imagining ourselves and our place in the world is terribly important in helping give us a sense of context, and in carrying out our daily activities. Our love for stories feeds this sense of imagination – and we feel more alive when our life is echoed in the imagination – it is a resonance chamber by which we build symphonies of meaning.

The Rooms

The tension in St. John’s is one of two imaginative visions: an elite version (which I suppose would be Laurin’s camp) and one down-home version (the CEO’s camp). Now, admittedly, I’m not in St. John’s and am only working with what I’ve read (today’s links) but let’s look at it according to Saul’s take on elitism. I believe, as does Saul, that people want what’s best. That only seems like common sense. Yes, the elites, and especially art-elites, do form a sort of tribe which treats people outside of it with an element of contempt. They think they are engaged in what’s best. They think that the lobster-trap craft folk are uneducated and misguided and have the blinders on towards ‘what’s best’. Hence, tension.

Ok, that being said, it does seem to me that Craig Power has a point where he writes, “Newfoundlanders have a reputation for being stupid, inbred and drunk. With the events of the past week and a half, is there any reason to wonder why?” having set it up by saying, “Wanda Mooney, a career government administrator, has been installed as interim director. … I don’t know what this woman’s knowledge of art history or contemporary art practice is, but I do know that if you Google her name, you find out that she used to be the woman you called if you wanted to rent space or book a reception at the old provincial gallery. How this qualifies her to run the gallery on even an interim basis, I don’t know, but I can hardly wait to see this visionary at work.”

Perhaps that’s unfair. But the point here is that according to the attitude among artists in St. John’s, the Board of Directors and CEO are suffering from a lack of imagination, one that in itself is contemptuous of the public at large. One that assumes tourists want to travel to foggy and cold St. John’s to see a bunch of folk-art crap, when they could be treated to the best of what contemporary culture has to offer.

But, the point I’m trying to make by bringing up London and my thoughts therein are that treating The Rooms with the contempt with which it has been treated, first by the Provincial Government, which kept it closed for a year, and now with Laurin’s dismissal, is stunting the imagination of Newfoundlanders, a place which so far has imagined itself as backward and victimized, and been rewarded by doing so by a Kevin Spacey movie. Laurin’s purported vision to give the citizens of St. John’s the quality of culture they deserve (that is, the best) and to resist mediocre crap, is admirable, and it’s unfortunate that another Maritime art scandal has resulted in the process. But here we also seem to be dealing with the backlash of ‘the excluded’ toward the elites (who have excluded by obscurantist writing and snotty attitudes for a century now) by treating them with ‘an equal contempt’.

Let’s just say that nobody has a monopoly on the imagination, but London also illustrates that it’s important to foster the best imaginations society has to offer.

-Timothy

I still think it’s safe to ride the subway.

I’m tempted to say ‘get a grip’ but it seems that the only people freaking out about the potential for terrorism in Canada, and in Toronto for that matter, are the news editors at the traditional outlets. I mean, remember a week ago, under these sweltering blue skies, when talk was on how crappy the Live 8 was and how the biggest threat to Canada was Karla Homolka, that psychopathic windbag who threatened to blow and blow and blow until our whole civil society came crashing down?

And then, Thursday morning, in London England, some bombs go off. Suddenly, Canada’s provincial sense of inferiority is nowhere to be found. Suddenly, all of our insecurities about not being able to play with the big boys are gone, because ‘oh my god, we’re next!’

Now, all we need is one or more nut-jobs to render what I’m saying here obsolete fast. But let’s not be superstitious about it. Let’s not think that just because I’m saying it ain’t gonna happen here means I’m jinxing it or something else. Granted, we should be vigilant. Granted, we certainly hope it won’t happen here. But I want to say this. I don’t think it’s going to happen here.

I say this with a sense of self-confidence, me, a pipsqueak citizen. The same self-confidence that our Ministers seem to lack in order to reassure the public. The same sense of self-confidence I use whenever I drive onto the 401. Sure, I could get killed, but why today? I know what I’m doing and I have to assume the other driving along do as well.

It would seem that our leadership doesn’t know what it’s doing. Let’s go over some points.

1. Ann McLellan sucks

I think back to October 2001 when suddenly she was the Iron Lady who was going to clamp down on our civil liberties and make sure that Canada wasn’t the so called terrorist haven that CBC documentaries would make it seem to be. Now she’s saying Canadians aren’t psychologically prepared for terrorism, which is a big help. Wonderful leadership. And what, pray tell, would be evidence that we are ready? And, with our history of bloodshed, why the hell should we be?

I’ll tell you about my psychological preparation for terrorism: after Sept 11, ‘life is short’ entered my vocabulary. Further, I developed an impatience described as ‘life is too short to put up with this bullshit’. Who wants to go to work one morning unprepared to become a skydiver and think of all the time we wasted listening to know-nothings and bastards? We all deserve better than the mediocre crap we are asked to put up with, and we deserve better than a Public Safety Minister like Ms. McLellan.

Prior to 9/11, I was dealing with a bout of hypochondria. Worried about this ache and that itch, suddenly the prospect of not seeing the end of a day that began with stupid anxiety was brought to my attention on repeat and with colourful graphics and passionate voiceovers. I learned on that day that one could go at any time, and I, in my practically atheistic way, said, ‘My life is in God’s hands’. We only have so much control over our lives, and let’s focus on what we can manage, and if our fate is to die because some jerk is trying to prove a point then well, what can you do?

2. John Bull’s Eye

London England – 2000 years old, long history of violence. Mobs there used to cart heads around on the end of pikes, but we’ve forgotten that. The news keeps talking about the Blitz, and something about the IRA (remember them)? London, England, home of the British Empire, which has been condemned by every politically correct academic for the past 40 years. London, where, in the months since September 2001, we have regular reports talking of terrorist drills, broken up rings, arrests made, and incidents quashed. Home to 7.5 million people. That’s a full 1/4th of Canada’s population right there. (All of Canada = 4 Londons).

Now, I raise this to say, of all the places in the world, after New York, it makes sense for bombs to go off in London.

History of violence and terrorism on a scale of 1 to 10: 10.

History of violence and terrorism in Toronto:1

(I’ll give it a 1 since there’s at least one shooting every weekend, and I don’t think we’ve had mob violence since the 1830s.)

3. Al Qaeda is a Phantom Menace

The best explanation of what’s happened over the past 4 years I’ve encountered has been Adam Curtis’s, The Power of Nightmares. This was broadcast on CBC Newsworld last spring, and was available on the Internet. The video has been take offline, but here you find a transcript of the episode I’m talking about. Now, The Power of Nightmares is a pretty straightforward account of the rise of both fundamentalist thinking in the States (in terms of the Religious Right, and the Neo-Con hawks) and of the Mid East. And here, we are told that Al Qaeda (essentially) doesn’t really exist. The story goes that in the aftermath of the 1998 Kenyan bombings, when the United States put one of the people they caught on trial in New York, they wanted to try Bin Laden in absentia. To do this, they needed to be able to claim/prove that he was part of an organized crime ring – these laws were developed to fight the Mafia. So, they get this fellow to tell a story about something called Al Qaeda, which is Arabic for ‘the Base’. Here, I might as well quote it:

“JASON BURKE , AUTHOR, AL QAEDA During the investigation of the 1998 bombings, there is a walk-in source, Jamal al-Fadl, who is a Sudanese militant who was with bin Laden in the early 90s, who has been passed around a whole series of Middle East secret services, none of whom want much to do with him, and who ends up in America and is taken on by-uh-the American government, effectively, as a key prosecution witness and is given a huge amount of American taxpayers’ money at the same time. And his account is used as raw material to build up a picture of Al Qaeda. The picture that the FBI want to build up is one that will fit the existing laws that they will have to use to prosecute those responsible for the bombing. Now, those laws were drawn up to counteract organised crime: the Mafia, drugs crime, crimes where people being a member of an organisation is extremely important. You have to have an organisation to get a prosecution. And you have al-Fadl and a number of other witness, a number of other sources, who are happy to feed into this. You’ve got material that, looked at in a certain way, can be seen to show this organisation’s existence. You put the two together and you get what is the first bin Laden myth – the first Al Qaeda myth. And because it’s one of the first, it’s extremely influential.”

The idea of global network of sleeper cells financed by Bin Laden is built up in the days after 9/11 by the NeoCons who want more money for the military-industrial complex. One of the main theses in The Power of Nightmares was that the core of NeoCons – Wolfowitz, Rummy, and the two Dicks (Cheney and Perle) had a long history of over-demonizing America’s enemy – whether it be USSR, or Ayatollah Khomeini (which lead to their support to Saddam Hussein in the 80s), to Saddam himself, and finally, prior to Bin Laden, Bill Clinton.

An arms race of nuclear weapons or a blow job – it was all the same to those jerks cause it got play on CNN and created an anti-Liberal culture unified by a common threat.

Al Qaeda then, would seem to be an elaborate fantasy. And perhaps this knowledge is worth spreading around. Funny though how traditional media haven’t really gotten into it.

The point I want to make here though is that when our city is marred, as it is from time to time, by hate graffiti against whatever ethnic group, CBC isn’t blaming it on an elaborate network of the Aryan Brotherhood. No, we assume it’s a bunch of punks. A bunch of local grown assholes, perhaps inspired by some underground hate-lit or vid. I’m thinking terrorism is working the same way today. Bin Laden might be the hate-pamphleteer, the author of the video Mein Kamp’s that supposedly make the rounds from mosque to mosque, attracting young romantic Islamists to training camps. But we’re dealing with a bunch of independent groups I think, local grown assholes. (And it should be pointed out that we aren’t even sure that Islamists were behind it yet).

London, apparently, had them. Does Toronto? That’s the question. If they do, then…

4. CSIS is incompetent?

John Ralston Saul’s anger toward the word ‘inevitable’ when used by economists and politicians to describe ‘globalizing forces’ over the past 30 years has sharpened me to being angry with the likes of McLellan and all these other so called experts. For them to sit there, on TV, and say, ‘oh, it’s gonna happen here …’ is an admittance of incompetence. It’s like they’re saying, ‘yeah, there are terrorist cells in Canada, we know that, and yeah, they’re probably planning something, but we can’t do anything about it.’ Are they still investigating Jadhi Singh I suppose? Going after the Raging Granies? Or, are they just covering their do-nothing asses by saying it’ll happen here in case something actually does and they were too busy eating donuts?

Basically, scare mongering isn’t going to help anyone. Further, I don’t see why Canada could be seriously considered a target for someone like Bin Laden. For impressionable young bastards from Markham …. who knows? But they’d have to build their bombs first, which would involve the procurement of materials and probably the access of certain websites. CTV and CBC would still rather tell us about the arrests of the local kiddie porn pervert than report such news. What does CSIS know? What aren’t we being told? But is it possible that in effect, there is nothing really to tell?

5. Vigilance

‘Report anything suspicious’. Right. One time I was on the Go Train and there was what I thought a suspicious package there. This was last winter or something. I have to parse this in light of all the paranoia. I think, ‘do I really want to bring the entire Go System to a complete stop just because some careless person forgot something?’ I decided to switch cars. I watched a Go employee walk right past it.

2nd story – CBC reports that VIA rail is investigating a security breach after a CBC employee boarded a train, entered the baggage area, and wasn’t checked for a ticket. I remember in 1995, riding from Moncton to Halifax, and talking with a girl who was careful to not run into the employees cause she was riding without a ticket. She made it sound bohemian and romantic. And I bring that up to say – I bet people ride VIA all the time without tickets. Perhaps this is Canada’s dirty little secret. Do you know someone who freeloaded a VIA ride?

And while we’re on the subject, I’ll bring up that I hate this type of reporter vigilantism. Remember how the Globe and Mail’s Jan Wong, in the months after 9/11, boarded a plane with what was then contraband – box cutter or the like? And then she writes about it as if things are so awful. The same woman who once spent an hour and half looking for kiddie porn in order to prove that it takes that long to find? Why aren’t these people arrested? If I was recruiting terrorists, I’d consider seducing reporters. It would seem a Press Pass is more valuable than a security clearance badge at the airport. You can get away with anything!

Reporter antics do not prove that security is lax. It might prove that these people, whose pictures often accompany their articles, or are seen on tv, are in effect ‘known’ by security. Jan Wong for example – shows up at the airport, has a knife in her purse, and is waived through because it’s known that she’s a just a reporter, and the thought is, ‘why would she do anything?’

The problem with vigilance, when talking about transportation systems, or in whatever other context, is that people are going to be preoccupied with what to them will be significant concerns. ‘I just want to get home,’ ‘I have to make this appointment’. ‘I don’t want to cause a scene…’

Do you remember the fellow in an American airport, who was seen running down an up-escalator? This was in November 2001. Anyway, because he ran down an escalator that was going up, because he was running late, he freaked out security, caused a scene, shut down the airport, and was arrested. He went to jail.

So, you shut down the subway system, inconvenience thousands including yourself, because someone forgot their umbrella, you won’t be called a hero, or congratulated for being vigilant in an era of paranoia. You’ll be vilified.

Now, I’m not saying this to discourage vigilance, or to say it doesn’t matter – I am though, simply trying to articulate what I think most of us would think when considering to hit the alarm strip. The TTC and Go Transit needs to do more to reassure us that we are allowed to do so because otherwise, ‘misuse can lead to fine or imprisonment’.

End the mixed messages and the scarmongering please. And I’ll see you on the subway.

Toronto is NOT next

I’ll make this short for once, because there’s not a lot to say beyond this: if you want to check out a year’s worth of Queen West shows in one weekend, make your way over to City Hall between Friday and Sunday to see all the art-stars and wannabes on display. I always find the stuff the art students are doing (who tend to be relegated to their own marginal section) to be worth checking out. Here’s the PR:

——————–

Toronto Outdoor Art Exhibition

July 8, 9, 10, 2005

Nathan Phillips Square, Toronto City Hall

Free Admission * Rain or Shine

Hours: July 8, 10am-8pm; July 9, 10am-7pm; and July 10, 10am-6pm.

Find paintings, drawings, sculptures, fibre works, jewelry, watercolours, metal works, original prints, ceramics, glass, wood works, mixed media works, and photographs by 530 artists and craftspeople!

Preview the artists’ work at www.torontooutdoorart.org

Win a $500 Art Shopping Spree! Tickets are $5 each. Buy them at the TOAE office or at the Main Information Booth at Nathan Phillips Square during the show.

For more information: 416.408.2754 or toae@torontooutdoorart.org

img: Scott Waters, Domestic: Cardinal, 2004, oil on wallpaper

In the future, people will consult machines, which will publish ‘you are’ books. Having analyzed you inside and out, through remarkably in depth ways – you will be presented with a canon of yourself. Thus defined you will either take comfort or squirm.

From the Tuesday’s

Hansard:

Hon. Jack Layton (Toronto-Danforth, NDP):

Mr. Speaker, it is a real privilege for me to stand in the House at this important and significant moment in Canadian history in the ongoing evolution and development of equality rights in our country. This issue is about families and it is about equal families. When we think of families, we immediately think of love.I would like first of all to salute a group which goes by the acronym of PFLAG, Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays. It might not seem that remarkable today that there would be an organization called Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, but many years ago when this organization came into being, not only was it difficult for a lesbian or a gay person to come out to his or her family, but it was very difficult for a family member to acknowledge to their broader community that their child was a lesbian, or a gay man. In fact, this is what precipitated the enormous feeling of loneliness which is the singlemost common sentiment that I have heard over the many years that I have been associated with the gay and lesbian community. They have a feeling of being alone with nobody understanding. In a sense they are fearful of what would happen if who they really were became public knowledge, became known to their family, to their friends, to their community.

There was justification for those fears. Far from a loving environment in the early days, certainly of my awareness of the community, the atmosphere within which gays and lesbians had to live in our country was one filled with hate. That hate was illustrated.