Doc Mod

defaults write com.apple.dock no-glass -boolean YES

killall Dock

defaults write com.apple.dock no-glass -boolean NO

killall Dock

This is the Mammalian Diving Reflex, a public report

Over the last 4 months, performance company Mammalian Diving Reflex has been to Mumbai, Lahore, New York, Dublin, Portland, Austria, Vancouver and Regina. We’ve walked through states of emergency, hung out in slums, met diplomats, had children cut our hair, got sick, had fights, offended powerful people and ate paan.

On Dec 21, at 7PM we’re presenting This is the Mammalian Diving Reflex, a public report. A presentation about who we are, what we do, why we do it, what we believe and where we’re going from here.

What: This is the Mammalian Diving Reflex, a public report.

Where: Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, 12 Alexander St, Toronto.

When: December 21, 2007, 7PM

How Much: PWYC

Mammalian Diving Reflex: Faisal Anwar, Stephanie Comilang, Natalie De Vito, Nick Murray, Darren O’Donnell and Rebecca Picherack.

More info: hello@mammalian.ca or 416 642 5772 – www.mammalian.ca

IDEAL ENTERTAINMENT FOR THE END OF THE WORLD

Site 1 (http://www.similarminds.com)

|

Main Type |

Overall Self |

|

|

|

Take Free Enneagram Personality Test

——————-

Site 2 (http://www.personalityonline.com/)

Enneagram – Your Results

Your Enneagram Type(s): Type 8

Eight’s need to be powerful to make their own way in life. They are motivated to maintain territorial control over anything that can influence their lives and by the desire to stay on top in any power struggle Of all the Enneagram types, they are the most openly aggressive. They are dominant figures both at work and at home.

They enjoy being strong and judge others according to whether those others are strong or weak. They also enjoy confronting others, and are even willing to take on the whole power structure if they feel a need for radical change. Eight’s are courageous and will crusade for what they believe in. They bring abundant energy to meeting challenges at work or elsewhere.

They are “natural leaders.” Their overwhelming self-confidence is contagious and can generate in others the energy that is necessary to accomplish monumental tasks.

You can get a full decription of the ‘type eight’ here.

From Goodreads 07w49:4

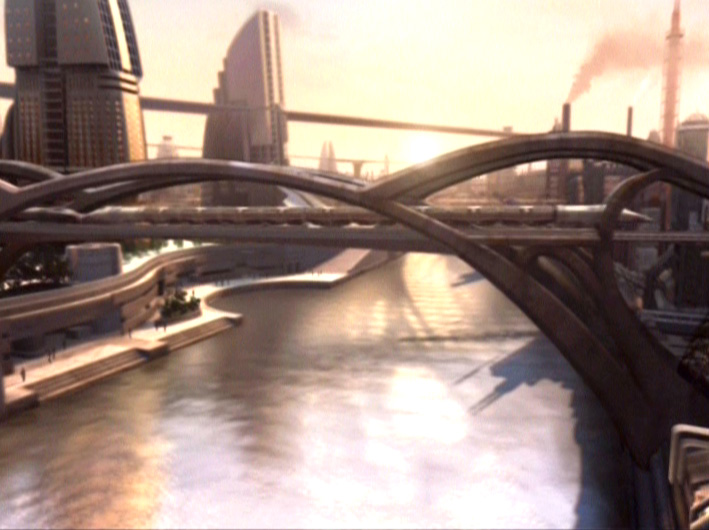

The 22nd Century is therefore marked by two cityscapes, one being that of Figure 1 the other being the following. These are meant to be Earth cities given the context of the time stream, but both shots are re-used production art from previous episodes. As I’ve mentioned, the cityscape below is from a Season 1 show (‘Dear Doctor’), while the bridge above is from an episode of Star Trek Voyager‘s last season (‘Workforce Part 1’).

With regard to Figure 3, because it is otherwise unlabeled and supposed to depict an Earth city in the 22nd Century, I thought it might as well be Toronto. We can imagine this stretch of waterfront as being a bit to the East, or a bit to the West, of the CN Tower thus accounting for its absence (or, I could just invite anyone to Photoshop it in). We can imagine the bridges are subway extensions to the island, and we see that a similar subway/covered LRT path runs right along the water.

This being an image originally from s-f, it reflects the current architectural trends of the beginning of the 21st Century, the postmodernist appreciation of angles, glass and concrete.

But I present this image to you thus as a reflection of what kind of city we’ll get if this century is to be one of starchitects. This is what another hundred years of Frank Gehry and Daneil Leibskinds will result in.

Does this city look like a place you’d want to live? We can spy green-space but it seems very sparse. And don’t give me the old, ‘who cares I’ll be dead’ routine, so common from the likes of the Baby Boomers. It’s precisely that type of attitude which has gotten us our present shit world, and I don’t want to encourage more of that. Given the extension of our lifespans over the past century, it’s not unreasonable to suggest that this could be the city of your elder years, so take the question seriously: is this where you want to hobble and feed pigeons? Further, are you so selfish as to be that uncaring about the type of environment our proverbial great-and-beyond-grandchildren will live in?

A much more dramatic depiction of the type of city we could end up with it that from Battlestar Galactica. Filmed in Vancouver, perhaps one could label this ‘Vancouver 2210 AD’ since it seems a bit more harsh than the aesthetic presented above, as if one needed another century to get both the flying cars and the brutal deadness of the civic space:

The real nightmare of urban development is this uniform cityscape of similar buildings, all equally unadorned, apparently utilitarian, with a neglected use of green space.

As spaces designed on computers to provide semiotic scenes meant to convey an advanced technological civilization, these reflect in turn the imagined futures of our own civilization. This is what we could end up with. But, in all likelihood, my guess is that the 22nd Century will not look like any of these images.

When Martin Rees published his book Our Final Hour in 2003, he famously gave our ‘civilization as we know it only a 50-50 chance of surviving the 21st century.’ (quote source) Now there’s some ambiguity there: others predict the potential extinction of humanity, which would certainly ruin our civilization, but it could also anticipate a sort of apocalyptic collapse into another form of Mad Max Dark Ages. But I have to point out the civilization known to the British in 1903 – and globally, that of every other nation and ethnic group on the planet (with the exception of those still living isolated tribal lifestyles) did not survive the 20th Century. The British Empire fell, the reliance on coal was replaced with that of processed crude oil, and the colonial projects of the era came to ignominious ends – the consequences of which we are still processing. Given how squanderous of natural resources our present civilization-as-we-know-it is, there’s no reason to want it to survive the 21st Century.

Which brings me to Prince Charles, who by the times spoken of here will be thought of as King Charles III. In the early 1980s, Charles was mocked by the media for his interest in organic farming, and he’s currently thought of as daft for his architectural interests, including his sponsorship of the community of Poundbury. Poundbury is the result of Charles’ interest in the work of Leon Krier and Christopher Alexander. As the Poundbury website records:

Poundbury is a mixed urban development of Town Houses, Cottages, Shops & Light Industry, designed for the Prince of Wales by Architect Leon Krier on the outskirts of the Dorset County Town of Dorchester. Prince Charles, The Duke of Cornwall, decided it was time to show how Traditional Architecture and Modern Town Planning could be used in making a thriving new community that people could live & work in close proximity. Poundbury has now become World Famous as a model of urban planning, with regular visits from Councillors and MPs. Welcome to the Poundbury Community Website!

Given how Charles has already displayed some prescience when it came to organic agriculture, anticipating both its sense and its popularity, my expectation is that he’s once again onto something with his interest in such small-scale, community oriented architecture. The end result will be cityscapes of the 22nd Century which will not reflect the imagined exaggerations of the present shown to us through easy digital mock-ups.

I return now to the city of the bridge. When I saw this in the Timestream montage, the lines of it brought to mind the position just stated: that by the 22nd Century, technological advance combined with a rejection of explicit postmodernist, angular, and Leibskind-like egotism will brings us a meld of the tradition and the technological. The bridged city seemed a place inspired by Lord of the Rings, a technological version of Rivendell.

Given a choice between Caprica, or the Toronto of 2110 suggested here, I’d take a Rivendell of any season, of any weather condition. Of course, I expect to be able to continue to use a high speed internet connection, use a cell-phone, browse in an Apple Store, and be able to have sushi. The point here is we can take much more control over our built environment, and expect more from our architects than glass and concrete. Letting current architectural fashion guide the next several generations will only result in a Caprica like monstrosity.- Timothy

Born in 1906, lived through the USSR.

John Ralston Saul, Voltaire’s Bastards (1992), pages: 503-504:

Buddhist societies are horrified by a great deal in the West, but the element which horrifies them most is our obsession with ourselves as a subject of unending interest. By their standards nothing could be unhealthier than a guilt-ridden1, self-obsessed, proselytizing white male or female, selling God or democracy or liberalism or capitalism with insistent superior modesty. It is clear to the Buddhist that this individual understands neither herself nor his place. He is ill at ease in his role; mal dans sa peau; a hypocrite taking out her frustrations on the world.

As for the contemporary liberated Westerner, who thinks of himself relaxed, friendly, open, in tune with himself and eager to be in tune with others – he comes across as even more revolting. He suffers from the same confused superiority as his guilt-ridden predecessor but has further confused himself by pretending that he doesn’t feel superior. While the Westerner does not see or consciously understand this, the outsider sees it immediately. The Westerner’s inability to mind his own business shows a lack of civilization. Among his most unacceptable characteristics is determination to reveal what he thinks of himself – his marriages, divorces and children; his feelings and loves. […] Any man or woman produced by the Judeo-Christian tradition is dying to confess – unasked, if necessary. What the Buddhist seeks in the individual is, first, that he understands he is part of a whole and therefore of limited interest as a part and, second, to the extant that he tries to deal with the problem of his personal existence, he does so in a private manner. The individual who appears to sail upon calm waters is a man of quality. Any storms he battles within are his own business.

Of what, then, does Western individualism consist? There was a vision, in the 19th Century, of the individualist as one who acted alone. He had to do so within the constrains of a well-organized society. Even the the most anti-restraint of thinkers – John Stuart Mill – put it that ‘the liberty of the individual must be thus far limited, he must no make himself a nuisance to other people’.2

But if the constraints of 19th Century Western civilization did put him in danger of causing a nuisance, he could simply go, or be sent to the frontiers of North and South America or to Australasia. […] Rimbaud fled Paris and poetry for an isolated Abyssinian trading post, where his chief business was rifles and slaves. This personal freedom killed him, as it did many others. […] Even without leaving the West, a man eager for individual action could find room for maneuver within the rough structures which stretched beyond the 19C middle-class society. In the slums, hospitals and factories, men from suffocating backgrounds could struggle against evil or good as if they were at war. By the 1920s, the worst of these rough patches were gone and the individual’s scope of action was seriously limited. In a stable, middle-class society, restraint was highly prized. Curiously enough, this meant that, with even the smallest unrestrained act, a man could make a nuisance of himself and thus appear to be an individual. 3

This is one explanation for the rise of artistic individualism – a form of existentialism which did not necessarily mean leaving your country, although it often did involve moving to the margins of society. The prototypes were Byron and Shelley, who fled in marital disorder across Europe, calling for political revolution along the way. Lermontov was another early model – exiled to the Caucasus, where he fought frontier wars, wrote against the central powers he hated and engaged in private duels. Victor Hugo was a later and grander example …4

Footnotes

1. In Greg Bear’s Queen of Angels the A.I. Jill’s analysis of punishment incorporates the thought that guilt is a result of our self-aware modeling, our recognition that we have failed somehow in the mind’s of Others. Jill thinks (p.417): ‘The self-aware individual in a judgment-society experiences guilt as a matter of course; to lack guilt, the individual must be poor at modeling and therefore inefficient in society, perhaps even criminal’. This line of argument is introduced on page 211, with the pseudo-author Bhuwani quote: ‘With self-awareness comes a sharper awareness of one’s place in society, and an awareness of transgression – that is, guilt.’

2. Consider how we live in a culture that makes a currency out of misery and problems, so that you end up talking about them in some social situation or another. How with someone you are likely to start gossiping about another person, their relationships and such, even though it’s none of your business. But, if you catch yourself doing this and want to take the high road and refuse to discuss what’s none of your business, you are more likely to hurt your conversant’s feelings. One needs to trade social information to maintain good relations. Similarly, one gets into discussing one’s problems for similar reasons. Trade your stories of misery so that we know you’re a member of the group, so that the others can feel good trying to help you and live with the illusion that they are either compassionate or not as bad off, and thus a little superior.

But, as above, becoming a nuisance to others by volunteering too much information about oneself is such a frequent occurrence nowadays. As Theodore Dalrymple as written, in this example describing an encounter with a dying man:

There had been no protest, no self-pity, no demand for special attention. He understood that I commiserated with him, though I said nothing except that I was sorry to see that he was unwell, but he understood also that my commiseration was of a degree commensurate with the degree of our acquaintance, and that demanded no extravagant and therefore dishonest expression. By controlling his emotion, and his grief at his own imminent death, so that he should not embarrass me, he maintained his dignity, and self-respect. He retained a sense of social obligation, a vital component of what used to be called character, until the very end of his life. I mention these people not because they were in any way extraordinary – a claim they would never have made for themselves – but because they were so ordinary. They were living up to a cultural ideal that, if not universal, was certainly very widespread (as my [foreign] wife would confirm). It is an ideal that I find admirable, because it entails a quasi-religious awareness of the metaphysical equality of mankind: that I am no more important than you. This was no mere intellectual or theoretical construct; it was an ideal that was lived. Unlike the claim to rights, which is often shrill and is almost so self-regarding that it makes the claimant the center of his own moral universe, the old cultural ideal was other-regarding and social in nature. It imposed demands upon the self, not upon others; it was a discipline rather than a benefit. Oddly enough, it led to a greater and deeper contentment, capacity for genuine personal achievement, and tolerance of eccentricity and nonconformity than our present, more egotistical ideals.

Dalrymple has said [in the CBC Ideas podcast, ‘The Ideas of Theodore Dalrymple’] that we treat emotion as type of pus that we feel must be released or else harm occurs. One ‘has to let one’s hair down’ etc; the abandonment of civilized restraint is popularly believed to be psychologically healthy.

3. Curiously enough, this meant that, with even the smallest unrestrained act, a man could make a nuisance of himself and thus appear to be an individual. Consider how at the 15th minute of Martin Scorsese’s Bob Dylan bio-documentary, No Direction Home (Part I) we get the interviews with Manchester’s 1966 youth, who are critical of Dylan’s turn to electric guitars and the apparent abandonment of his previous acoustic folk singing. The young men are thoughtful in their answers, but one says he thinks Dylan’s gone commercial, that he thinks ‘he’s prostituting himself’. ‘Prostituting himself’ is said as it comes to mind, said strongly into the camera’s lens, and when finished this boy smiles slightly, proud of his act of strong words. This is soon followed by a young man whose thoughts on it are equally considered but at 15:41 he says, ‘this I just can’t stick,’ and then catches himself with sudden upraised eyebrows and a muttered ‘excuse [me]’, as if we was expecting a whack upside the head from a schoolmaster for his indiscretion.

Of course, in today’s world, such young men (and women) would be inarticulate and full of (probably drunken) swagger, wearing some fucking t-shirt with a message printed across it and saying whatever came to mind, and if it needed bleeping, so be it.

4. Of the likes of Byron: the so called romantic figure, the romantic genius. Richard Rorty, (an excerpt from an audio interview, played on Australian ABC’s Philosopher’s Zone in their tribute program after his death) said:

I think individual romantic figures like Coleridge, Emerson, Whitman, Nietzsche, Derrida, are people who are engaged in romantic projects of self-creation, and this means, in the case of thinkers and poets, finding words that have never been spoken before, words that have no public currency, no public resonance, though they may become the literal meanings, the common coin of future generations.

And in an interview conducted for the RU Sirius program in August 2005, Rorty said,

Novels certainly suggest new ways of doing things. Revolutionary political manifestos, poems, religious prophecies, they all stimulate the youth to make themselves different from their parents and thus produce a human future different from the human past.

He had made similar points before, and this can be found in his 1989 book, Contigency, Irony, and Solidarity (on page 7):

What the Romantics expressed as the claim that imagination, rather than reason, is the central human faculty was the realization that a talent for speaking differently, rather than for arguing well, is the chief instrument of cultural change. What the political utopians since the French Revolution have sensed is not that an enduring, substratal human nature has been suppressed or repressed by ‘unnatural’ or ‘irrational’ social institutions but rather that changing languages and other social practices may produce beings of a sort that had never before existed.

The previous pages had this:

Europe did not decide to accept the idiom of Romantic poetry, or of socialist politics, or of Galilean mechanics. That sort of shift was no more an act of will than it was a result of argument. Rather, Europe lost the habit of using certain words and gradually acquired the habit of using others. As Kuhn argues in The Copernican Revolution, we did not decide on the basis of some telescopic observations … that the Earth was not the centre of the universe, that macroscopic behavior could be explained on the basis of microstructural motion, and that prediction and control should be the principal aim of scientific theorizing. Rather, after a hundred years of inconclusive muddle, the Europeans found themselves speaking in a way which took these interlocked theses for granted.

In other words, the contributions made by the 19th Century ‘romantic figures of self-creation’ was to add new, inspirational language to the discussion, through their novels, plays, and poems. In the case of Rimbaud, the package of consists in adding to the language and then the example of abandonment.

To be engaged in such a project, of discovering for oneself both a language and life, required defiance, and it created the contemporary social condition that John Ralston Saul describes in the chapter from which I took the excerpt above. JRS’ point is to say that the conditions of defiance in the 19th Century is far different from that of the late 20th and early 21st. This is because, as Rorty says on page 55 of the Contingency book:

The creation of a new form of cultural life, a new vocabulary, will have its utility explained only retrospectively. We cannot see Christianity or Newtonianism or the Romantic movement or political liberalism as a tool while we are still in the course of figuring out how to use it. For there are as yet no clearly formulatable ends to which it is a means. But once we figure out how to use the vocabularies of these movements, we can tell a story of progress, showing how the literalization of certain metaphors served the purpose of making possible all the good things that have recently happened. Further, we can now view all these good things as particular instances of some more general good, the overall end which the movement served. […] Christianity did not know that its purpose was the alleviation of cruelty, Newton did not know that his purpose was modern technology, the Romantic poets did not know that their purpose was to contribute to the development of an ethical consciousness suitable for the culture of political liberalism. But we now know these things, for we latecomers can tell the kind of story of progress which those who are actually making progress cannot. We can view these people as toolmakers rather than discoverers because we have a clear sense of the product which the use of those tools produced. The product is us – our conscience, our culture, our form of life. Those who made us possible could not have envisaged what they were making possible, and so could not have described the ends to which their work was a means. But we can.

JRS’ point in this chapter is to critique how our culture which supposedly privileges romantic rebellion, is in fact conformist. As he says, closing the section from which the excerpt is taken: ‘Today’s individualism can’t really be compared to all this existential activity. Is there a relationship between frontiersman and the self-pampering modern dentist? Between the French Legionnaire and the downhill-skiing Porsche driver? Between the responsible citizen of a secular democracy and the executive cocaine sniffer? All these people were and are engaged in a form of defiance. But there does not appear to be much room for comparison. The phenomena belong to separate worlds.’

The world that we belong to has been created by the example of the 19th Century Romantics, but we do not carry on their legacy. Rather (as a society) we’ve found new ways to conform, ways which we aren’t fully conscious, or understanding of. In the process, we have now generally become more obnoxious, since our defiance has become normalized. We’ve become nuisances to one another, without having experienced the peace of mind that comes from minding our own business. Within this circumstance their is still a need for individuals-who-wish-to-do-so to act out in ‘romantic projects of self-creation’ yet one hopes that they strive to create a new language, rather than learn to speak an already established one.

Therefore hipsters, shave your mustaches.

I’m still at the point where I can’t even imagine fifty-years. My equivalent of this photo (fifty years after graduating from high school) is the year 2043, by which time I hope the world will be unbelievably different in a good way. Bush and Co will long be dead, there will be peace in the mid east, the most of the Boomers will be cremated ash, except for those few trillionaires who insist on injecting themselves with all sorts of weird shit to stay alive for-ever (and they will probably have a whole television station devoted to the 1960s, Woodstock, Bob Dylan, fast machines, and the emotional aftermath of the Vietnam War, and the fact that they’re all still alive and how they’re ‘revolutionizing the centenarian years’).

Rebbecca Young had this in her Facebook, and I’ve decided to fill it out too:

Single or Taken: single

Happy about that: not really

Siblings: a sister

Eye color: brown

Height: 5’11

Can you make a dollar in change right now?: yes considering I’m at my desk and my change jar is to my right.

FAVORITES

Kind of pants: I don’t even know how to describe pants

Number: 15 comes to mind

Animal: nothing comes to mind. Oh wait, maybe bears. Also I currently have a thing for eagles but that’s only because of a recent read novel.

Drink (non alcoholic): water

Sports: none

Month: October

Juice: Orange

Favorite cartoon character: Bugs Bunny maybe. Cartman from South Park comes to mind too.

HAVE YOU EVER…..?

Given anyone a bath?: No

Bungee Jumped? : No

Made yourself throw-up?: No

Eaten a dog: Only hot dogs

Loved someone so much it made you cry?: yes if you mean from heartbreak

Played truth or dare?: yes

Been on a plane?: yes

Came close to dying?: not really

Been in a sauna?: I don’t think the ones at the community pool counts, so no, but yes if they do.

Been in a hotub?: yes

Swam in the ocean?: yes

Fallen asleep in school?: yes

Ran away?: no

Broken someone’s heart?: I really don’t think so. But maybe. I wouldn’t know.

Cried when someone died?: yes

Cried in school?: Yes. Elementary school sucked that fucking much.

Fell off your chair?: yes

Sat by the phone all night waiting for someone to call?: Maybe back in the mid-90s, but certainly not recently.

Saved MSN conversations?: Yes

Saved e-mails?: All the time

Used someone?: I would have to say yes.

Been cheated on?: I don’t think so.

WHAT IS…

your good luck charm?: I don’t have one.

your new favorite song?: ‘Music is my hot hot sex’ by Cansei de ser sexy

beside you?: tape dispenser, swiss army knife, desktop clutter to right. book shelves, printer, window to my left

last thing you ate?: apple muffins

What kind of shampoo/conditioner do you use?: anti-dandruff stuff

EVER HAD…

Chicken pox: yes

Sore Throat: yes

Stitches: yes

Broken a bone: no

DO YOU…

Believe in love at first sight?: yes

Have a Long distance relationship?: no

Like school?: no

Who was the last person that called you?: the girl from the agency

Who was the last person you slow danced with?: It’s been too many years for me to remember that.

Who makes you smile the most?: Danielle Williams

Who knows you the best?: Maybe Danielle? But I don’t feel well known by anyone at all.

Do you like filling these out: I’m doing it aren’t I?

Do you wear contact lenses or glasses?: both

Do you like yourself: yes

Do you get along with your family?: yes

ARE YOU…

Suicidal? : no

What did you do yesterday: not much. today was more productive

Gotten any awards?: yes

What car/truck do you wish to have?: none

Where do you want to get married?: I don’t really go for marriage stuff.

Good driver?: yes

Good Singer?: no

THIS OR THAT..

Scary or Funny Movies?: hate scary, funny: Big Leibowski comes to mind. There are others of course, but this is my favorite.

Chocolate or Vanilla? : chocolate

Root beer or Dr.Pepper? : root beer

Skiing or Boarding?: neither

Summer or Winter?: this year it’s winter

Silver or Gold? : sometimes silver, gold’s got something going on to, but for the most part I find the whole affection for such metals absurd.

Diamond or Pearl?: neither

Sprite or 7up? : they’re the fucking same

Coffee or Sweet tea? : coffee

Are you oldest, middle or youngest? : oldest

TODAY DID YOU…

Talk to someone you liked: no

Buy something: no

Get sick?: no

Talked to an ex? : no

miss someone?: no

LAST PERSON WHO…

Slept in your bed?: me

Saw/heard you cry?: no one

Made you cry? : i don’t really remember crying stuff. My Dad though comes to mind

Went to the movies with?: I think that must have been Ed, back in February.

Ever been in a fight with your pet?: no pets

Been to Mexico?: no

Been to Canada?: live there

Been to Florida? : no

RANDOM…

do you own a lava lamp?: no

How many remote controls are in your house?: More than I can think of

What was your last dream about?: Not sure about last night, but a couple of nights ago I dreamt I was getting arrested at a Guantanmo Bay conference.

What book are you reading now?: more than I want to list here

Best feeling in the world?: orgasm

Future KIDS names?: Coco if it’s a girl, boy undecided

Do you sleep with a stuffed animal?: no

What’s under your bed?: papers

Favorite sports to watch?: none

Favorite Locations?: nothing comes to mind, ‘cept maybe some parks

Piercing/Tattoos?: no

Who do you really hate?: Members of the Bush Administration but upon them I wish peace (props to the metta meditation training).

Do you have a job?: not presently

Have you ever liked someone you didn’t have a chance with?: all the time

Are you lonely right now?: yes

Song that’s stuck in your head right now?: maybe the Hot Hot Sex one above

Have you ever played strip poker? no

Have you ever been on radio/TV?: yes

Ever liked someone, but thought they’d never notice you?: all the fucking time. in fact, related to your last question, I like someone right now who was on tv today.

Whats the first things you notice about the opposite sex (visual)?: if I’m behind them its the ass, from the front face

Are you too shy to ask someone out?: not if I’ve been drinking

Butter, Plain or Salted popcorn?: butter and salted, but only when I indulge

Dogs or cats?: dogs

Favorite Flower?: hibiscus maybe?

Do you like to travel by plane as opposed to car?: no

How many pillows do you sleep with?: three

How long did it take you to do this survey?: I didn’t keep count

1982: The first edition of Blade Runner is released on 25 June.

1992: The second edition ‘Director’s Cut‘ is released on 11 July. At the time I’m a student of history and as a pet project I’m trying to write a history of Earth from the vantage point of the year 2400. In order to conceptualize the 22nd Century, I look to Blade Runner, and the images found in magazines, which are promoting the release of the Director’s Cut. But I live in rural Nova Scotia and I only know one person in my class who’s even heard of Blade Runner.

1993: I’m in Toronto that March, and look for a copy of the movie to buy. It’s not in stores anywhere.

Which is to say, it took me a few years before I got to see it for the first time. And once I did, it wasn’t the story-line that mattered so much as the sets; for years I’ve watched this movie as a series of montages in fantastic settings, the story-line connecting the scenes seemingly incidental and not even that interesting.

1999: I watch the Director’s Cut for the first time, and I find the extreme letter-boxing distracting to the extant that makes it almost unwatchable. I had the chance to see it on the big screen that spring but decided a now forgotten ’round-table’ conversation on art-something at the Khyber was more important.

So I can’t remember when I first saw Blade Runner, but it was probably one of the CityTv broadcasts that they ran on New Year’s Eve/Day at midnight through the 1990s. Ten years ago, January 1 1998 at 12am I recorded this broadcast and brought the VHS tape back to Halifax with me, where it quickly became wall-paper. Whenever it rained that year I would on returning to my small one bedroom basement apartment at the end of the day put in this copy and let in play in the background as I went about my work.

Later I found the Director’s Cut in the video store and rented it. I think that was the last time I watched the film straight through, sometime after its release in February 1999, and with memories of the voice over in mind, I had an its interpretive slant on the images. I found the Director’s Cut version was superior in its subtlety. This film, without Harrison Ford telling you what to think, invited you to consider it on your own terms.

At the time, Blade Runner was part of my extra curricular studies which also included the novels of William Gibson. For a time I was confused and thought I’d read somewhere that Blade Runner had influenced the writing of Neuromancer, (and later read that Gibson had actually been far more influenced by Alien, and imagined Neuromancer as a bit of background to that world). Given that the 21st Century was looming on us all in the late 90s, and my excitement at seeing that s-f time become real, Blade Runner and Gibson’s Sprawl Trilogy were part of a process of understanding what kind of world I’d spend the rest of my life in.

Walking up Spring Garden Road in 1999, and seeing the recently installed refurbished pay phones, I recognized their design as something ‘futuristic’ (a term that I hear less and less often these days) and something that would have looked fine in Blade Runner. There seemed to be an attempt to update our world to match the set design of 1980s s-f films, and given how such films then as now use the experimental work of industrial designers, this all made perfect sense. In that way, s-f films function as marketing for new designs. It seems to me that things like Blackberries and iPods are so successful since they were preceded by lengthy marketing campaigns in the form of s-f novels and films, so that when they arrived, we knew what they were, and had a good idea of what we could do with them.

Watching Blade Runner and reading Gibson’s Sprawl Trilogy was a way of prepping myself for the life I expected in Toronto, where I knew I’d end up. In fact, Gibson’s descriptions of the Sprawl always reminded me of Scarborough, so at first, experiencing mini-mall urban decay and franchise restaurants had the excitement of visiting a film-set from the future.

(I had the same experience when I visited Ottawa in early October 2000, just after Trudeau’s funeral, and the city reminded me of San Fransisco as seen in the Star Trek Voyager episode ‘Non Sequitur‘. Ottawa had not only cleaned itself up for the new century, but it was also a giant film set, constantly on our television screens hosting those actors of Parliamentary debate. Meeting someone by the Peace Flame, I looked down at the roses laid in honour of Trudeau’s memory, the flag above the Peace Tower at half-mast, as I’d seen in on television in the days before).

So to see Deckard eating noodles in 2007 is a different experience than seeing the same in Halifax in 1998, where chopstick joints were few and far between as they say. There was a Japanese restaurant on Argyle St but I was still too much of hick to understand the menu. Of course, after these years in the Toronto, Blade Runner just seems like a rainy night on Spadina, only more congested with archaic neon logos. Our bars aren’t filled with smoke and clay pipes, and while it probably will cost $1.25 to use a pay-phone in twelve years, the real Deckards by then are much more likely to use an old fourth generation iPhone.

As Gibson was saying over this past summer’s book-tour, even imagining a future in the first half of the 1980s was an act of optimism. I’m old enough to remember television stories about the Cold War and talk of Nuclear Winter. Blade Runner too offered a vision of the future, not quite post-apocalyptic but close, based loosely on Dick’s novel, which had projected a post-nuclear envirocide where ‘real’ animals were all but extinct. The novel’s Deckard dreamed of buying a ‘real’ goat as that society’s status symbol (as I recall, but I read the novel fifteen years ago). Now the movie has eclipsed the novel and the focus on artificial animals seems out of context, and we have a different understanding of artificiality. There’s enough GMO stuff around already that doesn’t seem any less ‘real’ to us, and the idea behind the Replicants is equally strange. Today it’s comprehensible as ‘Oh, there just genetically engineered humans with a four year life-span,’ which is a different play on 1982’s confusing ‘are they robots or something? How are they fake?’ And as we approach November 2019, it’s one time cyberpunk has become steampunk. Maybe our computers will accept voice commands by then, but we won’t have CRT-television set-top scanners at work printing out Polaroids of our 600+dpi zoom.

And it’s such scanning tech which has enabled this final cut version to come out. The original print was scanned at such an extremely high resolution that watching this version of Blade Runner is a new enough experience in itself – such clarity of image and level of detail was never seen before. This ‘restoration’ reminded me of that done on Michelangelo’s Sistine Ceiling – we live in an era of restoration, the grand updating to reflect cinema’s recorded vision, our imaginations inhabited by visions focused through Carl Zeiss lenses. Some critics then complained that the ‘brightening’ that occurred with the Michelangelo restoration destroyed the experience, while others welcomed the return to the ‘original’ condition.

Which is to say that the 21st Century experience of Michelangelo’s ceiling is different from that of the 19th, when the paintings were obscured by three centuries of candle-smoke and the like. And so with Blade Runner: in twelve years time, when it’s actually November 2019. undoubtedly this version of the film will be playing in theatres, and I most likely will find myself in front of the big screen once again, remembering both the time in 2007 when I saw it and the Halifax of twenty one years before. And if the film then still has any currency with the twenty-somethings of that world, what will their experience be of a quaint steam-punk movie depicting questionable dating practices (a forty something throwing a 20 year old girl up against the wall and telling her to say ‘kiss me’, followed the next day with a ‘do you love me?’ question), congested public spaces filled with cigarette smoke, and a level of visual detail lost on the earliest versions of the movie? Will copies of the original voice-over narrated film still be watched, or as ignored as the as murky as the reproductions of the Sistine Ceiling made in the 1960s? Treated, if anything, as historical curiosities, but not invitations to historical experience.

My sense is that Blade Runner is one of those rare works of art which is a master piece despite everything. One feels watching this that no one involved in the actual production had any idea they were making a masterpiece, and watching in straight through as I did, with the scenes visually clarified to highlight how they work together gives one the sense that the plot is kind of weak, in some places (as mentioned above with the romantic scenes) nonsensical, and that this film continues to work for the special effects alone. (It’s a silent movie originally provided with two voice-overs and now only one remains. Blade Runner is probably worth watching with Vangelis’ soundtrack alone). As a masterpiece it gets away from all intentions of its creators and that is one of the reasons it rewards viewing. No one knew what the fuck was going on with it or why, but it just works.

I’m reminded here of Malcolm Gladwell’s ‘story telling problem‘: that when we are confronted with something new we may not have ready-at-hand language to describe how we think about it or how it makes us feel. This in turn can cause us to make simplistic decisions rather than go with more ambiguous and complicated ones. This is how I understand the motivation for the first version’s voice-over narration. It was felt that the film needed some language to orient the viewer. But because this movie is so much about it’s visuals, it should be thought of as a form of animated narrative painting, for which language is not necessary.

So why then record my thoughts on it as I have? Because when I come home from seeing it on the big screen again in November 2019, I’ll want to read this record of what I thought of seeing it in 2007. And for that matter, I might as well share.

Blade Runner: The Final Cut will be released on DVD (in a 2-disc or 5 disc set) on December 18th.

Worth quoting in full (after all, it is a press release) with emph mine:

What’s in a name? Initials linked to success, study shows (Link)

Do you like your name and initials? Most people do and, as past research has shown, sometimes we like them enough to influence other important behaviors. For example, Jack is more likely to move to Jacksonville and marry Jackie than is Philip who is more likely to move to Philadelphia and marry Phyllis. Scientists call this phenomenon the “name-letter effect” and argue that it is influential enough to encourage the pursuit of name-resembling life outcomes and partners.

However, if you like your name too much, you might be in trouble. Leif Nelson at the University of California, San Diego and colleague Joseph Simmons from Yale University, found that liking your own name sabotages success for people whose initials match negative performance labels.

In their first study, Nelson and Simmons investigated the effect of name resemblance on batters’ strikeouts. In baseball, strikeouts are recorded using the letter ‘K.’ After analyzing Major League Baseball players’ performance spanning 93 years, the researchers found that batters whose names began with ‘K’ struck out at a higher rate than the remaining batters. “Even Karl ‘Koley’ Kolseth would find a strikeout aversive, but he might find it a little less aversive than players who do not share his initials, and therefore he might avoid striking out less enthusiastically,” write the authors.

In a second study, the researchers investigated the phenomenon in academia. Letter grades are commonly used to measure students’ performance, with the letters ‘A,’ ‘B,’ ‘C’ and ‘D’ denoting different levels of performance. Nelson and Simmons reviewed 15 years of grade point averages (GPAs) for M.B.A. students graduating from a large private American university.

Students whose names began with ‘C’ or ‘D’ earned lower GPAs than students whose names began with ‘A’ or ‘B.’ Students with the initial ‘C’ or ‘D,’ presumably because of an unconscious fondness for these letters, were slightly less successful at achieving their conscious academic goals.

Interestingly, students with the initial ‘A’ or ‘B’ did not perform better than students whose initials were grade irrelevant. Therefore, having initials that match hard-to-achieve positive outcomes, like acing a test, may not necessarily cause an increase in performance. However, after analyzing law schools, the researchers found that as the quality of schools declined, so did the proportion of lawyers with name initials ‘A’ and ‘B.’

The researchers confirmed these findings in the laboratory with an anagram test. The result of the test confirmed that when people’s initials match negative performance outcomes, performance suffers. These results, appearing in the December issue of Psychological Science, provide striking evidence that unconscious wants can insidiously undermine conscious pursuits.

###

Author Contact: Leif Nelson ldnelson@ucsd.edu

Psychological Science is ranked among the top 10 general psychology journals for impact by the Institute for Scientific Information. For a copy of the article “Moniker Maladies: When Names Sabotage Success” and access to other Psychological Science research findings, please contact Catherine West at (202) 783-2077 or cwest@psychologicalscience.org.

The Rady School of Management at UC San Diego educates global leaders for innovation-driven organizations. A professional school within one of the top-ranked institutions in the U.S. for higher education and research, the Rady School offers a Full-Time MBA program, a FlexMBA program for working professionals, undergraduate and executive education courses. Our lineage includes 16 Nobel Laureates (former and current faculty) and eight MacArthur Foundation award recipients. The Rady School at UC San Diego transforms innovators into business leaders.

Comments: I’m thankful that the author of this press-release took the time to explain letter grades to me, and thought it was interesting that students with initials ‘a’ and ‘b’ did not perform better than students with grade-irrelevant initials, which is only the entire rest of the alphabet. This alone seems to make such a correlation absurd.

The only reason I’d understand having the scale explained is to account for the international audience, but then again, this is written in English, so it’s not like there are a ton of Chinese out there who suddenly know about how North American grading works. For the Europeans, I imagine they’ve watched enough American movies and television to already be familiar with the system.

Is the argument then that the increased ’slightly less’ performance of the world’s Cynthia Donaldsons, Charles Davies’, Duncan Camerons is based partially on their names? So you’re saying that the reason Albert Burns got an 80, whereas David Connors got a 78 is because of their names?! Is this is why Cory Doctorow believes in ‘anti-copyright policies’!?

And this from a school that considers itself an educator of global leaders! No wonder the world is so fucked up. For one thing, such a study takes for granted a measurement of success which is itself a social construction dating back a century and out-of-step with the needs of present society. For example I imagine that to graduate with top marks from an MBA school you’d need to do rather poorly in the ethics department, especially environmental ethics. Failing the Humanities would also help, since at no point should you consider your employees as human beings desiring to live full lives. They must be refered to as ‘human resources’ (which would have served as a perfectly adequate term for slavery). Their natural desire to be as richly compensated as your gang at the top of the hierarchy must be kept in check and exploited for ’superior job performance’.

The fact that they felt the need to explain to us the letter-grade system seems to be evidence of an inability to imagine another, from which the ethical disasters of capitalism naturally follow. Further, the awarding of the marks leading to grades is mostly arbitrary, and dependent on many factors, including the fact that teachers are as biased as any other human being. So Connor gets 77 while James gets 80 because the teacher likes James more and gave a slightly higher mark to his answers over Connor, who doesn’t say a lot in class.

This study is trying to suggest that Connor, Cory, Charles, Cynthia, Duncan, David, etc, have an ‘unconscious attachment’ to their initials and are thus sabotaging their ’success’ in order to see it written on their tests as a reward counterbalancing the anguish of feeling like a failure. Not to mention the subsequent mockery from the class’ ’successful’ students (a mockery which is ‘unconsciously’ endorsed by the teacher since schools are supposed to help establish the pecking order, so that the authors of this press-release and study get sorted by high grades into university; then onto Masters and PHD programs and are then able to conduct such stupid studies open to such easy mockery).

As for the quoted baseball example, it is equally absurd and subject to the same critique offered above.

In my arbitrary grading system, based on my measurements of success, this study gets an F. Or, no, no, I’ll make the system so that L and N are the lowest grades, and J isn’t much higher, to make it fit with Leif Nelson’s and Joseph Simmons’ thesis.

Cento, 17 October 1786. Evening

I am writing from Guercino’s home town and in a better mood than I was in yesterday. Cento is a small, clean, friendly town of about five thousand inhabitants. As usual, the first thing I did was to climb the tower. I saw a sea of populars among which were small farms, each surrounded by its own field. It was an autumn evening such as our summer rarely grants us. The sky, which had been overcast all day, was clearing as the cloud masses moved northward and southward in the direction of the mountains. I expect a fine day tomorrow.

I also got my first glimpse of the Apennines, which I am approaching. Here the winter is confined to December and January; April is the rainy month, and for the rest of the year they have fair, seasonable weather. It never rains for long. This year September was better and warmer than August. I welcomed the sight of the Apennines in the south, for I have had quite enough of flat country. Tomorrow I shall write from their feet.

Guercino loved his native town as most Italians do, for they make a cult of local patriotism. This admirable sentiment has been responsible for many excellent institutions and, incidentally, for teh large number of local saints. Under the master’s direction, an academy of painting was founded here, and he left the town several pictures which are appreciated by the citizens to this day, and rightly so.

I liked very much one painting of his which represents the risen Christ appearing to His mother. She is kneeling at His feet, looking up at Him with indescribable tenderness. Her left hand is touching His side just below the wound, which is horrible and spoils the whole picture. He had His arm around her neck and is bending backward slightly so as to see her better. The picture is, I will not say unnatural, but a little strange. He looks at her with a quiet, sad expression as if the memory of His suffering and hers had not yet been healed by His resurrection, but was still present in His noble soul. Strange has made an engraving of this picture and I should be happy if my friends could at least see that. […]

As a painter, Guercino is healthy and masculine without being crude. His work has great moral beauty and charm, and a personal manner which makes it immediately recognizable, once one’s eye has been trained to look for it. His brush work is amazing. For the garments of his figures he employs particularly beautiful shades of reddish-brown which harmonize very well with the blue e is so found of using. The subjects of his other paintings are not so happy. This fine artist tortured himself to paint what was a waste of his imagination and skill. I am very glad to have seen the work of this important school of painting, though such a hasty look is insufficient for proper enjoyment.

Today of course, people are like ‘Hey, check out my Flickr account!’

It’s not so simple as saying we have something called computers which are connected to a network of wires. They’d be like, what? Our intuitive understanding of the Internet comes from our understanding of things like photographs, phones, and television.

So, Galileo walks into a bar…

First, we learned of a way to preserve the image projected by a lens.

Then we discovered that many such images, seen quickly in succession, would appear to move.

Then we harnessed the power of lightning. We learned it was a type of liquid which we could transmit things through, like the way sound can travel great distances in bodies of water. Just as water can become a part of the air through boiling, so too could the liquid of lightning become part of the air, and we found a way to take our images, which when strung together and looked at quickly would appear to move, and we turned them into air, so that people with boxes all over the world could see these moving images. These boxes were really just fat framed piece of glass, all the parts making it work residing inside. It would just run through the images we had beamed through the air using electricity. We also found a way to document sound, and so when we synced up the sounds to the moving images, it looked like the people were as alive as they appear to us now.

This was about seventy years after we learned of a way to transmit voices using the power of lightning through wires which we strung between cities and homes in a vast fisherman’s web of connections.

(// Q: But why explain TV?

A: Because you need to get them to imagine things moving on glass screens.)

So, we’d found a way to make things move on pieces of glass, using the power of lightning. And we had this network of lines through which we could talk to one another. It took some work but we found a way to hook up the two, and so in the eventually we had these pieces of framed super-glass hooked up to this network, and the glass displays whatever we want on it – printing type, paintings, our mechanic images so described above (which we call ‘photographs’ which is just a pretentious was of saying ‘light drawing’). They are like windows only we can chose what to see through them.

From Goodreads 07w45:3:

November in Canada is a season of two contradictory impulses. The first is the Massey Lectures, a series of five one hour lectures delivered on CBC Ideas for a work-week sometime during this month. The Massey Lectures to me represent some of the better characteristics of our species: the desire to not only grow in knowledge, but to communicate it as well. This lecture series invites the so called expert to break down the professional linguistic barriers that too often separates them from a broad audience.

The Massey Lectures used to invite scholars and writers of international habitation, but since the mid-nineties have focused on Canadian speakers, highlighting how much excellent thinking is being done by Canadians. My own excessive fondness for the work of John Ralston Saul stems from his delivery of the 1995 Massey Lectures, and my support of Michael Ignatieff’s quest for the Liberal leadership (and the subsequent eventual likelihood of Prime Ministership) comes from his 2000 Lectures (and in that case, it wasn’t so much the content of his talks, which was on human rights, but the fact that Canada deserves to have a Prime Minster who’s intelligent enough to have delivered the talks in the first place). Other past notables of the Massey Lectures include Charles Taylor (who delivered the 1991 Lectures) and Northrop Frye (in 1962; the series The Educated Imagination I consider to be essential reading).

Prior to the can-con, Noam Chomsky taught us about the media-as-propaganda model in 1988, and Dorris Lessing taught us about ‘the prisons we live inside’ in 1985. Lessing’s lectures were re-published by the House of Anansi Press last year, just in time for this year’s Nobel win to spike sales, and I picked up my copy the other day.

This brings me to the other side of Canadian November, and that’s the poppy. This is the impulse which contradicts our desire for knowledge (that desire to grow as individuals and as a species) and that is the desire for barbaric violence. The poppy sentimentalizes what should be considered simply shameful. How can its motto of ‘lest we forget’ still be said after 90 years of more war after that ‘war to end all wars’? It’s shame should be apparent in this embarrassment.

This year I’ve decided to boycott this emblem of remembrance, because I’m tired of war, I’ve had an ear and eyeful from the news all year and I want nothing to do with it. I don’t support the troops, I think Western governance has gone on a patriarchal war-is-glory bender and whatever threats exist are only exaggerated to promote the real agenda, which is an ancient Roman ideal of glory in death, destruction, and the vanquishing of enemies. Fuck all of that.

In her first lecture twenty-two years ago, Lessing brought up the unspoken facet of violence and war which she had witnessed in her lifetime, and that was that war was for many people fun. She opens her talks with a tale of a farmer who’s expensively imported bull had killed the boy who took care of it, and that this farmer decided to kill the bull because in his mind it had done wrong. She also tells of the post-WW II symbolic trial and ‘execution’ of a tree that had been associated with General Petain. Lessing points out that the farmer’s actions, and the villagers who destroyed a tree, were irrational, acting out of symbolism but not sense. As she says, ‘I often think about these incidents: they represent those happenings that seem to give up more meaning as time goes on. Whenever things seem to be going along quite smoothly – and I am talking about human affairs in general – then it is as if suddenly some awful primitivism surges up and people revert to barbaric behavior.’ Later, she writes:

To return to the farmer and his bull. It may be argued that the farmer’s sudden regression to primitivism affected no one but himself and his family, and was a very small incident on the stage of human affairs. But exactly the same can be seen in large events, affecting hundreds or even millions of people. For instance, when British and Italian soccer fans recently rioted in Brussels, they became, as onlookers and commentators continually reiterated, nothing but animals. The British louts, it seems, were urinating on the corpses of people they had killed. To use the word ‘animal’ here seems to me unhelpful. This may be animal behavior, I don’t know, but it is certainly human behavior, when humans allow themselves to revert to barbarism. […] In times of war, as everyone knows who has lived through one, or talked to soldiers when they are allowing themselves to remember the truth, and not the sentimentalities with which we all shield ourselves from the horrors of which we are capable … in times of war we revert, as a species, to the past, and are permitted to be brutal and cruel. It is for this reason, and of course there are others, that a great many people enjoy war. But this is one of the facts about war that I think is not often talked about. (p.15-16)

It is my sense, as noted above, that the Western world has not grown out of the immaturity of its violent, Imperial and Roman past. It used to be the comparison between the United States and Rome was a metaphor, and it has now become an analogy. It can be argued that since the Renaissance the Western project has been the resurrection of the Roman political state.

There is a reason why Roman dramas are part of our televisiual schedules, and that the actors speak with English accents, and that reason is simply that to a contemporary audience at mid-20th Century, when these dramas began to be made, the English accent was associated with Empire, but we still have not shifted to Roman dramas of American accents. Perhaps that wouldn’t be ‘exotic’ enough. Perhaps because American Empire is Robert Duval saying he loves the smell of napalm in the morning, or a cowboy falling on a nuclear weapon, or Nicholson telling us we can’t handle the truth. A Roman drama with American accents wouldn’t work because we associate American Empire with a vulgar New World technological advantage and Ancient Rome still sounds better in an Old World voice.

Cue Dante. This is written as an introduction to the link below, a discussion on Dante’s Paradiso, a recent translation of which has just been published. I’ve tried to read the Paradiso more than once over the past few years and always find it extremely boring, and that’s part of my point. There is a reason why the dark, violent, Hell-Vision of Dante is more often translated, more often talked about, more often borrowed for a cinematic vision. Because we are still barbarians. Resurrecting Rome while still caught in a Dark Ages mind-set that likes all this violent shit. (Beowulf anyone?).

And yet, seven hundred years ago, in the midst of that Middle Age between the light of Empires, a man imagined Heaven. It has been said that this alone should be heralded, as a supreme accomplishment of the human imagination. And that is why I’ve tried to read and appreciate it. Because it represents something other than violence and darkness, and if we find it boring, it’s because we still allow ourselves to be thrilled by cruelty and brutality. We still pay money to see digital humans ripped apart by monsters, fake blood flying everywhere. The Romans had least had the balls to do it for real, they didn’t try to hide behind our ’special effects’ which somehow is supposed to do two things: maintain a moral vision of human worth (which is continually contradicted by the cruelties in the news) and prevent us from seeing the dubious morality of being entertained by violence.

And so, a conversation on Dante during the season of Ideas and poppies. – Timothy

I upgraded WordPress yesterday and ran into some problems today with the .htaccess rewrite rules, which I’ve just fixed. I’m sharing these rules below. This is for people who are looking to write .htaccess rules for their WordPress setup and need some idea of how to go about doing that.

Note: this is for a custom-structure setting of /%post_id%/. Modify your’s accordingly.

For Months:

RewriteRule ^blog/date/199([0-9]+)/([a-zA-Z0-9]+)$ /blog/?m=199$1$2 [L]

RewriteRule ^blog/date/199([0-9]+)/([a-zA-Z0-9]+)/$ /blog/?m=199$1$2 [L]

RewriteRule ^blog/date/200([0-9]+)/([a-zA-Z0-9]+)$ /blog/?m=200$1$2 [L]

RewriteRule ^blog/date/200([0-9]+)/([a-zA-Z0-9]+)/$ /blog/?m=200$1$2 [L]These are doubled to account for an absent trailing slash.

For Months that are broken into pages (again doubled for a missing slash, and here I’m not taking into account any postings from the 1990s):

RewriteRule ^blog/date/200([0-9]+)/([a-zA-Z0-9]+)/page/([a-zA-Z0-9]+)/$ /blog/?m=200$1$2&paged=$3 [L]

RewriteRule ^blog/date/200([0-9]+)/([a-zA-Z0-9]+)/page/([a-zA-Z0-9]+)$ /blog/?m=200$1$2&paged=$3 [L]For basic entries:

RewriteRule ^/blog/?p=([a-zA-Z0-9]+)$ /blog/$1 [L,R=301]

RewriteRule ^blog/([a-zA-Z0-9]+)/$ /blog/?p=$1 [L]

RewriteRule ^blog/([a-zA-Z0-9]+)$ /blog/?p=$1 [L]The first rule above takes into account anyone’s old links to your pages using the default format. The second rule assumes a trailing slash, and the third rule assumes a forgotten slash.

For pages:

This example uses my About page, which under the default url-setting has an id of 2. Again doubled for slashes:

RewriteRule ^blog/about/$ /blog/?page_id=2 [L]

RewriteRule ^blog/about$ /blog/?page_id=2 [L]Categories are similar:

RewriteRule ^blog/category/uncategorized/$ /blog/?cat=1 [L]

RewriteRule ^blog/category/zeitgeist/$ /blog/?cat=9 [L]With Categories you need to set up the rules to match the category name with its id number. Although as of the latest iterations of WordPress, categories have been replaced with tags, and I haven’t fully crossed-over to that yet, so I’m not sure what’s involved there.

Andrew Sullivan writes about Barack Obama (via Richard Florida’s blog):

Consider this hypothetical. It’s November 2008. A young Pakistani Muslim is watching television and sees that this man—Barack Hussein Obama—is the new face of America. In one simple image, America’s soft power has been ratcheted up not a notch, but a logarithm. A brown-skinned man whose father was an African, who grew up in Indonesia and Hawaii, who attended a majority-Muslim school as a boy, is now the alleged enemy. If you wanted the crudest but most effective weapon against the demonization of America that fuels Islamist ideology, Obama’s face gets close. It proves them wrong about what America is in ways no words can.

THEN

A slight young man who was considered a god king 3329 years ago when he died. With a long narrow skull which some people make out to be part of an ancient alien-worship cult, but that’s another story. He lies in his box for those thirty centuries while the world slowly turns into airplanes, nuclear weapons and the idiocies of television. Three thousand two hundred and forty-four years after his death, English colonials raid the tomb and use hot knives to remove the famous golden mask, glued to his face. Media frenzy ensues. A boy-king legend in born. King Tut enters the vernacular.

NOW

The USA is collapsing. Is this like the USSR circa 1988?

Event InfoName:FORUM – Paradise Lost: Romanticism’s Return

Tagline: with Max Allen, GB Jones, Katherine Lochnan & John Potvin

Host: The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery

Type: Music/Arts – Performance

Time and PlaceDate: Thursday, November 1, 2007

Time: 7:00pm – 9:00pm

Location: The Power Plant

Street: 231 Queens Quay West

City/Town: Toronto, ON

View Map

Contact InfoPhone: 416.973.4949

Email: thepowerplant@harbourfrontcentre.com

Description

From the glam rock band Scissor Sisters to Sophia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette, contemporary culture is infatuated with ecstatic, anguished decadence. Responding to Paul P.’s interests in the dandyism of writer Marcel Proust and painter James McNeill Whistler, this forum considers the resurgence of romanticism, touching on issues of artist relationships and personae, 19th Century portraiture, pornography’s infiltration of visual culture, and images of desire and loss.

Chaired by Max Allen, producer/host of CBC’s IDEAS, speakers include GB Jones, artist/musician whose work appeared with Paul P.’s on the cover for The Hidden Camera’s The arms of his ‘ill’; Katherine Lochnan, Senior Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Art Gallery of Ontario and curator of ‘Turner, Whistler, Monet’ which toured to Tate Britain and Musée d’Orsay; and John Potvin, author of Bachelors of a Different Sort whose research concerns the male body and intimacy in Victorian and Edwardian culture.

Take the emphasis on professional sports. It sounds harmless but it really isn’t. Professional sports are a way of building up jingoist fanaticism. You’re supposed to cheer for your home team. Just to mention something from personal experience – I remember, very well, when I was I guess, a high school student – a sudden revelation when I asked myself why am I cheering for my high school football team. I don’t know anybody on it, if I met anybody on it we’d probably hate each other. You know, why do I care if they win or if some guy a couple blocks away wins? And then you can say the same thing about the baseball team or whatever else it is. This idea of cheering for your home team -which you mentioned before – that’s a way of building into people irrational submissiveness to power. And it’s a very dangerous thing. And I think it’s one of the reasons it gets such a huge play. Or . . . let’s move to something else. The indoctrination that’s done by T.V. and so on is not trying to pile up evidence and give arguments and so on. It’s trying to inculcate attitudes. I mentioned a couple of cases but there are a lot more. Let’s take, say, the bombing of Libya. Why did the American public support the bombing of Libya? Well, the reason is that there had been a very effective, and careful, and intense inculcation of racist attitudes about Arabs. Anti-Arab racism is the one form of racism in the United States that’s considered legitimate. I mean, plenty of people are racist, but you don’t like to admit it. On the other hand, with regard to anti-Arab racism you admit it openly. You read a journal like, say, The New Republic, and the kinds of things that they say about Arabs . . . if anyone said them about Jews you’d think you were reading (Der Stern). I’m not joking. And nobody notices it because anti-Arab racism is so profound. There are novels that have a form of anti-Arab racism that’s hair-raising. The same is true of television shows and so on and so forth. An image has been created – the media are part of this, not all – of the Arab terrorist lurking out there ready to kill us. And against that background you could bomb Libya and people would cheer. Recall how effective that was, remember what was happening in 1986, there are a lot of measures of how effective this is. Remember that in 1986 when this happened the tourism industry in Europe was virtually wiped out because Americans were afraid to go to Europe, where incidentally, objectively, they would be about a hundred times as safe as in any American city. That’s no joke. But they were afraid to go to Europe because they got these Arab terrorists out there trying to kill us. Now, that was not from New York Times editorials, that was from a whole array of television and novels and soap operas and a mass of symbolism and so on and so forth and that’s effective. The anticommunist hysteria is developed that way too. The communists are out there ready to kill us – who are the communists? – I don’t know, they’re out there ready to kill us. This is introduced by the kinds of symbolism that T.V. is good at, and cheap novels are good at and so on and that’s important. These are critical means of indoctrination it’s just that I wasn’t talking about them. I was talking about the more intellectual side.

(source)

From The End of Virtuous Albion, (on the British National Character), by Theodore Dalrymple (originally published in the New Criterion, 1 September 2005):

On walking through the hospital in which I formerly practiced, I came across the husband of a patient of mine who had always accompanied her to her appointments. He was sitting down and waiting to be called for an examination. He was much thinner than I had seen him before, and he was so jaundiced that he was almost orange in color. At his age, this could mean only one thing: hepatic secondaries in the liver, and fast-approaching death.

I passed the time of day with him, and wished him and his wife well, though I knew that he was dying, he knew that he was dying, and he knew that I knew that he was dying.

“We’ll just have to do the best we can” he said.

Indeed, he died two weeks later. There had been no protest, no self-pity, no demand for special attention. He understood that I commiserated with him, though I said nothing except that I was sorry to see that he was unwell, but he understood also that my commiseration was of a degree commensurate with the degree of our acquaintance, and that demanded no extravagant and therefore dishonest expression. By controlling his emotion, and his grief at his own imminent death, so that he should not embarrass me, he maintained his dignity, and self-respect. He retained a sense of social obligation, a vital component of what used to be called character, until the very end of his life.

I mention these people not because they were in any way extraordinary–a claim they would never have made for themselves–but because they were so ordinary. They were living up to a cultural ideal that, if not universal, was certainly very widespread (as my wife would confirm). It is an ideal that I find admirable, because it entails a quasi-religious awareness of the metaphysical equality of mankind: that I am no more important than you. This was no mere intellectual or theoretical construct; it was an ideal that was lived. Unlike the claim to rights, which is often shrill and is almost so self-regarding that it makes the claimant the center of his own moral universe, the old cultural ideal was other-regarding and social in nature. It imposed demands upon the self, not upon others; it was a discipline rather than a benefit. Oddly enough, it led to a greater and deeper contentment, capacity for genuine personal achievement, and tolerance of eccentricity and nonconformity than our present, more egotistical ideals.

While Kate Blanchette in armour and on horseback, with long red hair flowing from her wigged scalp, looking a good twenty years younger than her supposed age of 55 (which in 16th Century terms is a miracle) is visually resplendent, it captures nothing of the woman who wrote Monsieur’s Departure.

I grieve and dare not show my discontent,

I love and yet am forced to seem to hate,

I do, yet dare not say I ever meant,

I seem stark mute but inwardly to prate.

I am and not, I freeze and yet am burned.

Since from myself another self I turned.

My care is like my shadow in the sun,

Follows me flying, flies when I pursue it,

Stands and lies by me, doth what I have done.

His too familiar care doth make me rue it.

No means I find to rid him from my breast,

Till by the end of things it be supprest.

Some gentler passion slide into my mind,

For I am soft and made of melting snow;

Or be more cruel, love, and so be kind.

Let me or float or sink, be high or low.

Or let me live with some more sweet content,

Or die and so forget what love ere meant.

– Queen Elizabeth I

_____________

“Monsieur” is identified in two MSS as the duke of Anjou, who withdrew from marriage negotiations in 1582, and in one MS as Robert Devereaux, earl of Essex, whose long-lived affection for Elizabeth ended in a rebellion that resulted in his execution on a warrant signed by Elizabeth. (source)

Goodreads | 2007 week 42 number 6 (Doris Lessing Selection)

From Doris Lessing’s introduction to The Golden Notebook (June 1971):

To get the subject of Women’s Liberation over with – I support it, of course, because women are second-class citizens, as they are saying energetically and competently in many countries. It can be said that they are succeeding, if only to the extent they are being seriously listened to. All kinds of people previously hostile or indifferent say: ‘I support their aims but I don’t like their shrill voices and their nasty ill-mannered ways.’ This is an inevitable and easily recognizable stage in every revolutionary movement: reformers must expect to be disowned by this who are only too happy to enjoy what has been won for them. I don’t think Women’s Liberation will change much though – not because there is anything wrong with its aims, but because it is already clear that the whole world is being shaken into a new pattern by the cataclysms we are living through: probably by the time we are through, if we do get through at all, the aims of Women’s Liberation will look very small and quaint.

But this novel [The Golden Notebook] was not a trumpet for Women’s Liberation. It described many female emotions of aggression, hostility, resentment. It put them into print. Apparently what many women were thinking, feeling, experiencing, came as a great surprise. Instantly a lot of very ancient weapons were unleashed, the main ones, as usual, being the theme of ‘She is unfeminine’, ‘She is a man-hater’. This particular reflex seems indestructible. Men – and many women, said that the suffragettes were de-feminized, masculine, brutalized. There is no record I have read of any society anywhere when women demanded more than nature offers them that does not also describe this reaction from men – and some women. A lot of women were angry about The Golden Notebook. What women will say to other women, grumbling in their kitchens and complaining and gossiping or what they make clear in their masochism, is often the last thing they will say aloud – a man may overhear. Women are the cowards they are because they have been semi-slaves for so long. The number of women prepared to stand up for what they really think, feel, experience with a man they are in love with is still small. Most women will still run like little dogs with stones thrown at them when a man says: You are unfeminine, aggressive, you are unmanning me. It is my belief that any woman who marries, or takes seriously in any way at all, a man who uses this threat, deserves everything she gets. For such a man is a bully, does to know anything about the world he lives in, or about its history…

[…]

This business of seeing what I was trying to do – it brings me to the critics, and the danger of evoking a yawn. This sad bickering between writers and critics, playwrights and critics: the public have got so used to it they think, as of quarreling children: ‘Ah yes, dear little things, they are at it again.’ Or: ‘You writers get all the praise, or if not praise, at least all that attention- so why are you so perennially wounded?’ And the public are quite right. For reasons I won’t go into here, early and valuable experiences in my writing life gave me a sense of perspective about critics and reviewers … It is that writers are looking in the critics for an alter ego, that other self more intelligent than oneself who has seen what one is reaching for, and who judges you only by whether you have matched up to your aim or not. I have never yet met a writer who, faced at last with that rare being, a real critic, doesn’t lose all paranoia and become gratefully attentive – he has found what he thinks he needs. But what he, the writer, is asking is impossible. Why should he expect this extraordinary being, the perfect critic (who does occasionally exist), why should there be anyone else who comprehends what he is trying to do? After all, there is only one person spinning that particular cocoon, only one person whose business it is to spin it.

It is not possible for reviewers and critics to provide what they purport to provide – and for which writers so ridiculously and childishly yearn.

This is because the critics are not educated for it; their training is in the opposite direction.

It starts when the child is as young as five or six, when he arrives at school. It starts with marks, rewards, ‘places’, ‘streams’, stars – and still in many places, stripes. This horse-race mentality, the victor and loser way of thinking, leads to ‘Writer X is, is not, a few paces ahead of Writer Y. Writer Y has fallen behind. In his last book Writer Z had shown himself as better than Writer A.’ From the very beginning the child is trained to think in this way: always in terms of comparison, of success, and of failure. It is a weeding-out system: the weaker get discouraged and fall out; a system designed to produce a few winners who are always in competition with each other. It is my belief – though this is not the place to develop this – and the talents every child has, regardless of his official ‘IQ’, could stay with him through life, to enrich him and everybody else, if these talents were not regarded as commodities with a value in the success-stakes.