Archive for April 2008

Warren Wagar, A Short History of the Future, page 244:

…sharp witted, yet outgoing and cooperative, the young members of Homo Sapiens altior fashioned a new model of human behavior ideally suited for life in autonomous communities. They were less inclined than the old human type to take advantage of others and too intelligent to be taken advantage of themselves. Their extraordinary powers of mind and heart were another form of wealth, shielding them, as ample personal incomes and education helped to shield everyone, from the age-old tendency of most of Homo sapiens to fall victim to predators.

As integration deepens, the generation whose identity was created by separation can feel left behind, betrayed, and lash out … at other members of the minority.

– Andrew Sullivan, parsing Wright, Sharpton, and Obama

You’ve suggested that there might be certain functions of the mind, certain aspects of consciousness, that don’t have a material foundation.

Yes.

Advanced contemplatives in the Buddhist tradition have talked about tapping into something called the “substrate consciousness.” What is that?

Just for a clarification of terms, I’ve demarcated three whole dimensions of consciousness. There’s the psyche. It’s the human mind — the functioning of memory, attention, emotions and so forth. The psyche is contingent upon the brain, the nervous system, and our various sensory faculties. It starts sometime at or following conception, certainly during gestation, and it ends at death. So the psyche has pretty clear bookends. This is what cognitive neuroscientists and psychologists study. They don’t study anything more. And they quite reasonably assume that that’s all there is to it. But as long as you study the mind only by way of brain states and behavior, you’re never going to know whether there’s any other dimension because of the limitations of your own methodologies. So here’s a hypothesis: The psyche does not emerge from the brain. Mental phenomena do not actually emerge from neuronal configurations. Nobody’s ever seen that they do.

So your hypothesis is just the reverse from what all the neuroscientists think.

Precisely. The psyche is not emerging from the brain, conditioned by the environment. The human psyche is in fact emerging from an individual continuum of consciousness that is conjoined with the brain during the development of the fetus. It can be very hampered if the brain malfunctions or becomes damaged.

But you’re saying there are also two other aspects of consciousness?

Yeah. All I’m presenting here is the Buddhist hypothesis. There’s another dimension of consciousness, which is called the substrate consciousness. This is not mystical. It’s not transcendent in the sense of being divine. The human psyche is emerging from an ongoing continuum of consciousness — the substrate consciousness — which kind of looks like a soul. But in the Buddhist view, it is more like an ongoing vacuum state of consciousness. Or here’s a good metaphor: Just as we speak of a stem cell, which is not differentiated until it comes into the liver and becomes a liver cell, or into bone marrow and becomes a bone marrow cell, the substrate consciousness is stem consciousness. And at death, the human psyche dissolves back into this continuum.

So this consciousness is not made of any stuff. It’s not matter. Is it just unattached and floating through the universe?

Well, this raises such interesting questions about the nature of matter. In the 19th century, you could think of matter as something good and chunky out there. You could count on it as having location and specific momentum and mass and all of that. Frankly, I think the backdrop of this whole conversation has to be 21st century physics, not 19th century physics. And virtually all of neuroscience and all of psychology is based on 19th century physics, which is about as up-to-date as the horse and buggy.

(source)

John Adams: Spring 1772

Government is nothing more than the combined force of society, or the united power of the multitude, for the peace, order, safety, good, and happiness of the people … There is no king or queen bee distinguished from all others, by size or figure of beauty and variety of colors, in the human hive. No man has yet produced any revelation from heaven in his favour, any divine communication to govern his fellow men. Nature throws us al into the world equal and alike … (source)

***

The preservation of liberty depends upon the intellectual and moral character of the people. As long as knowledge and virtue are diffused among the body of a nation, it is impossible they should be enslaved …

(source)

***

Ambition is one of the more ungovernable passions of the human heart. The love of power is insatiable and uncontrollable…

There is danger from all men. The only maxim of a free government ought to be to trust no man living with power to endanger the public liberty. (source)

***

Better that many guilty persons escape unpunished than one innocent person should be punished. “The reason is, because it’s of more importance to community, that innocence should be protected, than it is, that guilt should be punished.” (pg 68) -Quoted from The Legal Papers of John Adams, Vol III, 242

In writing this book, I have made a host of spelling “mistakes”, but have paid them no heed. Each has been signaled clearly by a red line that my computer’s U.S. text system inserts beneath the offending word. The mistakes aren’t really mine, though; they are Macdonald’s. He had an order-in-council passed directing that the government’s papers be written in the British style, as with “labour” rather than “labor”.

(p66) In 19C Canada, the observation that all politics is local would have been treated not as insight but as a banality. With occasional exception, such as the campaign to achieve Responsible Government by Population, almost all politics was about local issues. Debates that engaged the general public were almost always those inspired by sectarianism – French vs English, Catholic vs Protestant, and sometime Protestant vs Protestant, as between Anglicans and Methodists. Just about the only non-religious exception to the rule was the issue of Anti-Americanism; it was both widespread and, as was truly rare, a political conviction that promoted national unity because it was held as strongly by the French and by the English.

Almost all politics was local for the simple reason that almost everyone in Canada was a local: at least 80% of Canadians were farmers or independent fishermen. Moreover, they were self-sufficient farmers. They built their own houses. They carved out most of their implements and equipment. They grew almost all their own food (tea and sugar excepted) or raised it on the hoof. They made most of their own clothes. They made their own candles and soap. Among the few products they sold into commercial markets were grain and potash. Few sent their children to school. They were unprotected by policemen (even in the towns in Upper Canada, police forces dates only from the 1840s). For lack of ministers and priests, marriages were often performed by the people themselves. Even the term ‘local’ conveys a false impression of community: roads were so bad and farms spaced so far apart that social contact was limited principally to ‘bees’ – barn and house raising, stump clearing and later, more fancifully, quilting.

Government’s reach in Canada was markedly more stunted than in England. While there had been a Poor Law there from 1597, the first statute of the Legislature of Upper Canada provided specifically that ‘Nothing in this Act … shall introduce any of the laws of England concerning the maintenance of the poor’. (The Maritimes, then quite separate colonies, had both Poor Laws and Poor Houses). The churches were responsible for charity, and in some areas for education (The first legislation in British North America to establish free education was in Prince Edward Island in 1852. Nova Scotia followed in 1864, and Ontario only after Confederation). It was the same for that other form of social activism, the Temperance Societies, commonly brought into being by the Methodist, Presbyterian and Baptist churches. The unemployed were ‘the idle poor,’ and no government had any notion that it should be responsible for their succor. Governments collected taxes (almost exclusively customs and excise duties) and were responsible for law and order, maintaing the militia, and running the jails, where the idea of rehabilitation as opposed to punishment was unknown. But without income tax, there was comparatively little the government could do even if it wished. Consequently, the total spending on public charities, social programs and education amounted to just 9% of any government’s revenues. To most Canadians in the middle of the 19C, government was irrelevant to their day to day lives as it is today to the Mennonites, Hutterites and Amish.

[…] In mid to late 19C Canada, conservatism was as widely held a political attitude as liberalism would become a century later. It took a long while for things to change. In one post-Confederation debated, in 1876, held during an economic depression, a Liberal MP argued that the government should assist the poor. Another MP rounded on him to declare “The moment a Government is asked to take charge and feed the poor you strike a blow to their self-respect and independence that is fatal to our existence as a people.’ The shocked intervenor was also a Liberal, as was the government of the day.

Amid this emphasis on the local, there was, nevertheless, one broad national dimension. Governments were remarkably ready to go into debt – proportionally more deeply than today – to build up the nation itself. Here, Conservatives were actually greater risk-takers than the Reformers. Bishop Joseph Strachan, a leading member of the arch-conservative Family Compact, held that ‘the existence of a national debt may be perfectly consistent with the interests and prosperity of the Country’. In the early and middle part of the century, mostly Conservative governments bankrolled major public projects – first canals, such as the Welland, the Lachine and the Rideau – and then a spiderweb of railways, nearly all of them money-losing. The Conservatives were, of course, undertaking projects that benefited their supporters, but they were also building the country. [… p 69]

p. 89 A great many Canadians have come to assume that their country began on July 1 1867, not least because we celebrate each year the anniversary of Confederation. But Confederation wasn’t the starting point of all that we no have and are. It developed from its own past, and that past, even if now far distant from us, still materially affects our present and our future.

The most explicit description of the continuity of Canadian politics across the centuries is made by historian Gordon Stewart in his book The Origins of Canadian Politics. There he writes, “The key to understanding the main features of Canadian national political culture after 1867 lies in the political world of Upper and Lower Canada between 1790s and the 1860s.” His argument, one shared fully by the author, is that all Canadian politics, even those in our postmodern, high-tech, 21st Century present, have been influenced substantively by events and attitudes in the horse-and-buggy Canada of our dim past.

[…]

The catalyst of fundamental change in pre-Confederation politics were the rebellions in 1837-38 by the Patriotes in Lower Canada led by Louis-Joseph Papineau, which was a serious uprising, and by the rebels in Upper Canada led by William Lyon Mackenzie, which was more of a tragicomedy. Both uprisings provided a warning to London that, as had gone the American colonies a half-century earlier, so the colonies of British North America might also go. To deal with the crisis, the Imperial government sent out one of its best and brightest.

John George Lambton, Earl of Durham, arrived accompanied by an orchestra, several race horses, a full complement of silver and a cluster of brainy aides, one of whom had achieved celebrity status by running off with a teenage heiress and serving time briefly in jail. Still in his early forties, ‘Radical Jack’ was cerebral, cold, acerbic and arrogant. After just five months in the colony, he left in a rage after a decision of his – to exile many of the Patriotes to Bermuda without the bother of a trial – was countermanded by the Colonial Office. Back home, he completed, in 1839, a report that was perhaps the single most important public document in all Canadian history. Lord Durham himself died of TB a year later.

Parts of Durham’s report were brilliant; parts were brutal. The effects of each were identical: they both had an extraordinarily creative effect on Canada and Canadians. The brutal parts of Durham’s diagnosis are, as almost always happens, much the better known. He had found here, he declared, “two nations warring in the bosom of a single state … a struggle, not to principles, but of races (Durham’s use of the word ‘race’ will strike contemporary [readers] as odd. It was used then to describe people now usually referred to as ‘ethnic groups’.) The French Canadians, les Canadiens, had to lose – for their own sake. They were ‘a people destitute of all that could constitute a nationality … brood[ing] in sullen silence over the memory of their fallen countrymen, of their burnt villages, of their ruined property, of their extinguished ascendancy.’

In fact, Durham was almost as hard about the English in Canada. They were ‘hardly better off than the French for their means of education for their children.’ They were almost as indolent: ‘On the American side, all is activity and hustle … On the British side of the line, except for a few favoured spots, all seems waste and desolate.’ He dismissed the powerful Family Compact as ‘these wretches’. Still, he took it for granted that Anglo-Saxons would dominate the French majority in their own Lower Canada. ‘The entire wholesale and a large portion of the retail trade of the Province, with the most profitable and flourishing farms, are now in the hands of this dominant minority.’ All French Canadians could do was ‘look upon their rivals with alarm, with jealousy, and finally with hatred.’

The only way to end this perpetual clash between the ‘races’ Durham concluded, was there to be just one race in Canada. The two separate, ethnically defined provinces of Upper Canada and Lower Canada should be combined into the United Province of Canada. As immigrants poured in from the British Isles, the French would inevitably become a minority. To quicken the pace of assimilation, the use of French should cease in the new, single legislature and government. To minimize the political weight of Lower Canada 650,000 people, compared with Upper Canada’s 450,000 each former province, now reduced to a ‘section’ should have an equal number of members in the new legislature. (Officially, Upper Canada now became Canada West, and Lower Canada became Canada East. In fact, almost everyone continued to refer to the new sections by their old titles … In fact, the legislature re-legalized the use of the old Upper and Lower Canada terms in 1849).

Durham’s formula worked – but backwards. Quebec’s commitment to la survivance dates less from Wolfe’s victory over Montcalm [in 17x] (after which the Canadiens’ religions and system of low were protected by British decree) than from 1839, when Durham told French Canadians they were finished. The consequences of this collective death sentence was an incredible flowering of a national will to remain alive. (A parallel exists with the publication in 1965 of George Grant’s Lament for a Nation predicting Canada’s inevitable absorption by America. In response, English-Canadian nationalists suddenly stood on guard for their country).

[…]

Few in Upper Canada noticed [the flowering of French-Canadian self-awareness]. Their attention was focused on the other part of Durham’s report, one calling for a totally different kind of Parliament. It was to be a responsible Parliament, with a cabinet composed of member of the majority party rather than chose at the pleasure of the governor general. In a phrase of almost breathtaking boldness, Durham wrote, ‘The British people of the North American Colonies are a a people on whom we may safely rely, and to whom we must not grudge power.’

– Richard Gwyn, John A. Macdonald Vol I 2007

The prevalence of pedantry at Rome was quickly followed by a decline of true taste, by a contempt of simplicity and nature, and by the substitution of false and affected beauties. Before the close of Augustus’s reign, a certain effeminacy of style insinuated itself at court; and the malignant criticisms of Asinius Pollio, and of his son Asinius Gellius, on the language and compositions of Cicero, greatly conduced to wean the Romans, as Denina expresses it, from that great fountain of Latin oratory. Eloquence was no longer to be seen in an elegant undress, but was always tricked, and flounced, and highly decorated with the studied graces of novelty, or the attractive glitter of points, of witticism, allusions, and conceits. The want of real dignity was supplied by a pompous strut; and artificial flowers were profusely scattered to conceal the decay of Nature’s sweetest blooms.

–The British Cicero: Or, a Selection of the Most Admired Speeches in the English Language; By Thomas Browne, 1808

***

It was the custom of those Roman Nobles, to spend their leisure, not in vicious pleasures, or trifling diversions, contrived, as we truly call it, to kill the time; but in conversing with the celebrated Wits and Scholars of the age: in encouraging other people’s learning, and improving their own: and here Your Lordship imitates them with success….

Conyers Middleton, Dedication to Lord Hervey / ‘The History and the Life of Marcus Tullius Cicero, 1755 viii

Despite Canada’s status as one of the larger donors, it has failed to meet a commitment to donate 0.7 per cent of its gross domestic product to the Millennium Project, despite a resource boom over the past few years that generated considerable economic wealth. Mr. Sachs said he was told on one occasion by a cabinet minister that Ottawa couldn’t boost its aid to meet this target because it would threaten the country’s budget surplus.

– Jeffery Sachs in today’s Globe & Mail: Canada deaf to growing hunger crisis, UN aide says by Sinclair Stewart and Paul Waldie

Norman Mailer: ‘One of the reasons Franklin Delano Roosevelt was so beloved one of the reason Jack Kennedy was so mourned is they were two of the rare examples of presidents trying to make the country more intelligent. They didn’t jump the easy conclusions all the time. When Roosevelt said ‘the only thing to fear is fear itself,’ he was introducing a concept into the public mind. He trusted the public to the extent that you could talk to them that way. Jimmy Carter tried but didn’t succeed. Remember he used that word ‘malaise’; ‘the country’s suffering from a malaise’ and of course that bombed. Well, Jimmy Carter had very good instincts up to a point but he didn’t have a sense of how to deal with the public. It’s a peculiar ability to raise the intelligence of the public and still know how to talk to them. [emp mine]

Norman Mailer, speaking in March 2006 (Mp3; 17:39):

NM: A democracy is a most delicate form of government, the most delicate, that’s why it took so long to arrive in history. It depends on the language of the people becoming more artful and richer, and more elevated if you will, over the decades and the centuries. And it depends upon more and more creativity and substantiality and fine institutions and high development. And Bush is a negative force against that because he reduces language. He’s an abominable speaker. He hide behind his … I won’t get into what he hides behind.

Dotson Rader: You’re making what are essentially aesthetic objections to Bush, which to the American people, the great unwashed performing seals out there they see as elitist. You’re not making political objections. You understand what I’m saying? You’re talking about ‘he’s debasing the language’ – well, advertising debases the language. The whole culture of America is one vast debasement of language.

NM: I will insist on one thing. A democracy is dependent on wonderful language, upon the language improving not deteriorating. This country was fabulous in the days of Franklin Delano Roosevelt because he spoke so well. The small taste we had of Jack Kennedy gave us the huge sense of will he felt … here was this intelligent man who obviously was indicating in subtle ways that he also wanted to improve the level of intelligence in politics and in America. Democracies are delicate. The opposite end of a democracy is fascism, always. Fascism is much more implanted in our nervous system than democracy. When we’re children, when we’re one, two, three, four years old, willy-nilly with the kindest parents in the world we’re nonetheless living in a fascistic environment if you will, a totalitarian environment, which is ‘do as you’re told’ we say to a child with all the art in the world, the child grows up knowing in some part of themselves that obeying orders is not the worst thing in the world.

DR: Well, I would say it’s a structured environment, I wouldn’t say it’s a fascistic environment.

NM: Well, the word is unpleasant and causes … but I want to underline and exaggerate it for a very direct reason. Which is democracies are always in danger of becoming fascistic, if they they turn corupt, if the people don’t become more and more intelligent and illumined, as they go along, through history, then they tend to deteriorate. I’ve said this over and over: one of the reasons the English did not collapse and go to pieces given all their reversals in the 20C is Shakespeare; just as the Irish, without Joyce, would have been much less. Now I’m not saying this just and only because I’m a semi-talented novelist. I’m saying it because language is immensely important, immensely important and Bush destroys it every time he opens his mouth.

~Earlier the same day:Norman Mailer on the Leonard Lopate Show (Mp3; 25:20), 2 March 2006

Norman Mailer: A democracy in my mind depends, absolutely depends upon the populace becoming more and more intelligent and sensitive and aware and nuanced over the decades. When a democracy becomes more stupid it’s in danger of becoming fascistic. It’s the duty I would say of a president to make a nation more intelligent. One of the reasons Franklin Delano Roosevelt was so beloved one of the reason Jack Kennedy was so mourned is they were two of the rare examples of presidents trying to make the country more intelligent. They didn’t jump the easy conclusions all the time. When Roosevelt said ‘the only thing to fear is fear itself,’ he was introducing a concept into the public mind. He trusted the public to the extent that you could talk to them that way. Jimmy Carter tried but didn’t succeed. Remember he used that word ‘malaise’; ‘the country’s suffering from a malaise’ and of course that bombed. Well, Jimmy Carter had very good instincts up to a point but he didn’t have a sense of how to deal with the public. It’s a peculiar ability to raise the intelligence of the public and still know how to talk to them.

From Bad Writing’s Back by Mark Bauerlein :

Still, despite the mannered presentation, Just Being Difficult? and previous pro-theory statements do forward responses that deserve a hearing. Theorists devote long paragraphs to them, but they can be distilled into blank assertions and treated as hypotheses. They are:

[…]

Scientists have their jargon—why can’t theorists have theirs?

Again, this is a valid question with a simple pragmatic answer. The public tolerates scientific jargon and not theory jargon because it believes that scientists need jargon to extend their researches and produce practical knowledge that benefits all. Only when scientists appear to abandon the common good does their language come under attack (for example, Swift’s portrait of mathematicians in Book III of Gulliver’s Travels, or contemporary ridicule of sociologese and psychobabble). Come the day when the theorists are able to demonstrate that their jargon enhances human life, and isn’t just pretension and science-envy, public mistrust of them will end. Constantly claiming to foment social justice isn’t sufficient.

[…]

The United States is an anti-intellectual nation, and its national publications follow the trend.

Most theorists take American anti-intellectualism for granted, and Brooks suggests that cultural journals have adopted the Right-wing view, although “there is perhaps no point in lamenting the decadence of the serious cultural journals since journals of any sort mainly go unread at present”. This is silly academic parochialism as its most cocksure. Theorists who lament the absence of serious criticism in the magazines and newspapers should limit their point to the fact that their version of criticism has no public venue. In truth, learned criticism appears in magazines and newspapers all the time. The New Republic (circulation 100,000 a week) publishes lengthy review-essays on scholarly subjects by humanities professors (e.g., David Bromwich, David Freedberg, and Lawrence Lipking), as does the New York Review of Books. The Nation publishes art criticism by Arthur Danto and literary essays by Morris Dickstein; and reviews in Atlantic Monthly by Benjamin Schwarz and others meet high intellectual standards. Wall Street Journal editor Erich Eichman allows academic reviewers 800 words on university press books covering unusual subjects, and the Los Angeles Times and Boston Globe have deliberately raised the content of their weekly reviews. Moreover, although Commentary and The New Criterion haven’t the subscriptions of the others, like the now-closed Partisan Review in earlier times, their influence reaches to politicians and public intellectuals. Dutton’s own webpage, Arts and Letters Daily, receives over two million page views per month. I could go on, but suffice it to say that the notion that public discourse in the U.S. is vulgar and decadent is an absurdity that academics should give up immediately.

[…]

With Hulme, creative artists break down the “standardised perception,” then “induce us to make the same effort ourselves and make us see what they see.” He doesn’t consider the case of the artist who works alone, forever estranged from the crowd. Adorno doesn’t talk about social success in the same way, but we can judge his effect simply by naming the people he influenced. These include not only contemporary theorists but also mid-century mass culture critics Dwight Macdonald, Clement Greenberg, Irving Howe, and others centered around Partisan Review—an audience skeptical and dogged enough to verify his brilliance.

We should apply the pragmatic test to today’s theorists. What if in the end nobody abandons common sense and adopts the theory habit? Butler aims to “provoke new ways of looking” and Culler repeats Emerson’s dictum, “Truly speaking, it is not instruction but provocation that I can receive from another soul,” but what if nobody is provoked? This is not quite the same verdict that Leftist critics of bad writing such as Katha Pollitt, draw, namely, that the theorists’ recondite language cuts them off from real politics. Rather, it recalls the simple truth that, as a matter of historical record, only certain disruptions thwart common sense and alter the world. In a word, the “anti-styles” only work if they create as well as destroy. If ordinary language is a repository of naturalized values, then the artist/critic’s counter-language must supply other values in infectious, admissible ways: one common sense world collapses only if another takes its place. If you propose to explode certain attitudes and beliefs, and to do so by disrupting their proper idiom, then you must compose a language compelling, powerful, memorable, witty, striking, or poignant enough to supplant it. Your language must be an attractive substitute, or else nobody will echo it.

Needless to say, the theorists haven’t achieved that and never will. A genuine displacement comes about through an original and stunning expression containing arresting thoughts and feelings, not through the collective idiom of an academic clique smoothly imitated by a throng of aspiring theorists. [emph mine] The writings of Pound, Mallarmé, Faulkner, and H.D. each form a unique signature and inspire theorists to daring interrogations, but few idioms are as conventionalized as 1990s critical theory. In her op-ed, Butler mentions slavery as a common-sense notion that had to go (Warner echoes the self-inflating comparison), but none of the abolitionists followed the “difficult writing” strategy. Frederick Douglass was a dazzling rhetorician, and Warner’s example, Thoreau, composed epigrams honored for their pithy brilliance. By comparison, theory prose is a clunker. Its success in the academy lies not in surprising conversions of common-sense minds, but in quick and easy replication by AbDs. If critics assume a duty to undermine common sense, very well, but they need to devise a different counter-speech, not insist on the value of their current one.

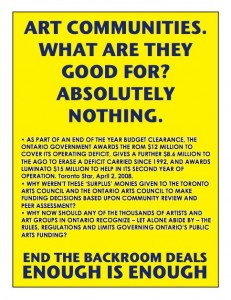

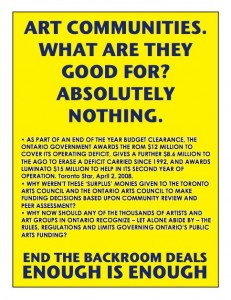

Marni Soupcoff called for the elimination of the artist grant system earlier this week and there’s been an expected response.

There are two types of artist I know: those who love the council-system and those who dislike it for encouraging ‘safe’ work.

I’m of the latter sort. My feelings are that the council system is made up of juries who are into one particular type of art. So, the assumption being that if you’re a painter specializing in the type of portraits and landscapes appreciated by grandmothers, you don’t have a chance of getting a grant. The so-called ‘safe’ work is whatever’s hip, and that’s impossible to pin down from year to year: it’s a fashion, it moves through communities as people imitate one another, it’s original source unknown and unimportant. In today’s globalized culture, the determination of what’s hip is dominated by bigger players, and is probably documented and originated in magazines like Artforum rather than C Magazine. (That’s a specifically visual-arts reference. There was a blurb I saw on a TV news channel scrawl saying that hip-hop is the least well funded of the all the art genres by the Canada Council, and yet hip-hop is obviously the most relevant music genre to most young people. The evident bias there is an example of my point).

I got a couple of grants in my time, and I appreciated them. They allowed me to execute projects without having to invest my own money, of which I had none. Looking back, I’m not sure if these projects meant much to society as a whole, which is why I no longer take the ‘art is important to society’ argument too seriously. I’ve come to think of art as something more private and personal. And I feel I make more money working than I would by relying on the hand-outs of grants and prizes. I dislike the current-system of cultural funding as it exists, but I wouldn’t support scrapping it altogether.

What I don’t like about this type of ‘taxpayer bitching’ is how the ‘angry conservative’ stereotype falls into ‘I don’t want them spending my money…’. I’ve always found this reason to be nonsense. I don’t understand why we don’t teach people to think of taxes as that salary we citizens pay toward the functioning of the state. Imagine if employers started saying, ‘I don’t want you spending my money on drugs, or drunken weekends, or McDonald’s hamburgers, or home stereo systems, or …’ etc. Employers know where to draw that line in minding their own business. We in turn should trust our governments to spend their funding responsibly, and when, as often happens, it is exposed that they haven’t been doing so, there should be scandal, there should be apologies and firings, and we appreciate the reforms that follow. Corruption should never be the norm, but it should never be unexpected either. ‘Show me a completely smooth operation,’ Frank Herbet wrote in one of his Dune novels, ‘and I’ll show you a cover up. Real boats rock.’ 1 In other words, human beings are never perfect, and we shouldn’t expect that.

It should not be the case however that the citizen comes to think of culture as an irresponsible expenditure, and yet that has been allowed to happen within my lifetime. We, as a first world nation, can afford to encourage the imagination. God knows we need to in this country.

We pay taxes and we expect a functioning public service and stable infrastructure in return. We aren’t the United States with a military industrial complex, wherein the government subsidizes global violence. We could instead have a cultural-industrial complex and the most we’d have to suffer is visual pollution and bad music, but it would be preferable to a painful and ugly death. Of course, this isn’t on the table because the money is currently in War, and so when we hear talk of Canadian governments trying to attract investment in science, we should ask, science for what? The fact that the Cdn Gov blocked the sale of MDA to land-mine-manufacturing ATK this past week shows that we aren’t immune to such questions and considerations.

When we are told triumphantly that the provincial and/or federal government is running a budget surplus, it is evident that they could be doing much more for the citizens. Unfortunately, a penny-pinching mentality has taken hold, which may be useful as private citizens (I’m currently in a penny-pinching mode myself) but I’m not sure it serves the public interest. If anything, governments should be more forthcoming about their plans for a surplus. Paying off some debt – fine. But holding on to it indefinitely? Not so fine. Are you trying to accumulate interest on the monies so that it grows further? Ok, sure. But when are we going to get a day-care system, and a guaranteed income, and bigger minimum wages, and fatter old-age pension cheques, and investment in affordable housing, better and more frequent public transit, lower tuition rates, cancellation of student-loan debt, and on and on…?

The government still seems to think that its constituents are ignorant people with personal attachments to numbers on pay-stubs who can somehow magically trace those exact numbers into the pockets of the so-called welfare mom all pissy because they’ve been legislated into civilized compassion. Soupcoff echoes this argument when she says ‘Canadians are accustomed to having their money transferred from their own bank accounts to those of the nation’s broadcasters, sculptors and poets.’ Soupcoff then plays a class-card, by writing, ‘Government funding ensures that every time these affluent aesthetes sit down to hear a live piano concerto, they enjoy a nice subsidy from lower-class taxpayers, who are sitting at home reading their Harry Potter books and listening to their Nine Inch Nails CDs. It just doesn’t seem fair.’

I for one have been to a live piano concerto, and that was when I could afford it under the TSO’s program of selling $12 tickets to those under 30. Since I’m now over 30, I haven’t been to the TSO in four years. I did however buy the latest Nine Inch Nails CD this past week, to listen to when I want a change from the classical music I used to stream from CBC 2 and which I now get from alternative outlets like Classical 96.3 or icebergradio.com. My personal example here to say that there’s room in life for both Harry Potter and Tolstoy, and that Nine Inch Nails is actually pretty good.

Class-based access to culture is the result of both education and pricing. But it’s also a question of interest. So what if some people just aren’t interested? I’m not interested in Harry Potter (I haven’t read any of the books or seen any of the movies) and in this binary I’m lucky: this makes me look like I made ‘the right choice’ to people like Harold Bloom, who would be happy to see me reading Macbeth if I was interested in magic. But if millions are loving Harry Potter, clearly I’m missing out on something. It’s just a question of taste. (And while Bloom has a point in questioning it’s literary value, life needs the occasional piece of candy).

Greater funding should translate in greater accessibility. The reward of the arts should be available to all. This argument justifies libraries: publicly funded knowledge made accessible. Would Soupcoff suggest we shut down all libraries because people can buy whatever books they want at Indigo/Chapters? My understanding is that type of argument would have been made in the 19th Century, when publicly funded childhood schooling was considered controversial. But we’ve come to take democratized education and accessible knowledge for granted. We are in the process of achieving a future society where the arts will also be taken for granted and be thus ensured against this type of financial short-sightedness. But we are not there yet.

Perhaps it needs to be said that the argument for ceasing funding was allowed to take hold because the arts were allowed to become incomprehensible. (It did not have to be that way, but that is past. The mistake is allowing it to continue).

To that end, Marni Soupcoff and I agree that, “The decision about what to watch — American Idol or A Beachcombers Christmas — should be one people make for themselves,’ but we do not agree that, ‘[it is]not one the government makes for them (or at least tries to: Despite its best efforts, the government still hasn’t succeeded in getting more than a handful of us to watch CBC television, even if we do pay for it).’ The Government doesn’t make us to anything. As for the CBC, our ‘failure to watch’ is indicative of the corporation’s mismanagement and cultural stupidity. They thought we wanted to watch ‘The One‘.

The traditionally called Higher Arts are more often than not rendered distasteful by being poorly taught, and those like myself who pursue them do so either because they weren’t taught at all (as in my case; no opportunity was taken to ruin them for me) or because the person has a inexplicable passion for them (which also used to be true in my case). Soupcoff: ‘But let’s be honest — who makes up the majority of the audiences of symphonies, art galleries and ballets? It’s middle-class and rich people who can afford to pay for their own entertainment.’

I hate ballet and I don’t understand why Karen Cain is a house-hold name and Jeff Wall is not. Nor, for that matter, why Rex Harrington’s retirement made it onto the CTV news in 2003. But it doesn’t bother me that it’s funded. I went to art school because I wanted to study the arts. For that I was seen by my conventional friends as being weird. I think it’s weird that Toronto has a ballet school, but that’s just to say I sympathize with its potential students, and I’m glad I live in a society where young girls who want to destroy their feet and starve themselves for the pleasure of jumping into the arms of a gay man have a place where they can go and feel welcome. In other words, it’s nice that people have options when it comes to doing something with their lives. And whatever encourages the broadening of those options is a good thing, even if it does to some seem weird.

To that end, we have the arts: it is the realm of imagination where alternative ways to think and live one’s life are fostered. For example, we have been progressively moving toward a more peaceful and ‘civilized’ (in the mannered since of the term) soceity2, inspired by the examples offered to us in movies and novels. Consider how Star Trek‘s universally acknowledged attraction is it’s vision of a future of inclusion and peace-on-Earth. But Star Trek is an American show and offers an American vision of an American future. If the CBC were living up to its mandate, it would support a Canadian future-based program, to give us some sense of what our future might be like. History is necessary, the present is obvious, but what kind of world are we moving toward? A valid question. We have too many future scenarios that offer dystopias, and we need more utopian ones to inspire us. This is not a job that funding ‘math and science’ will do for us. If the math-n-science is to take us to the Moon and Mars, ask where the idea of going off-world came in the first place.

On the April 7th 2008 episode of TVO’s The Agenda, Steve Paikin asked former Ontario Finance minister Greg Sorbara how high the arts rated in the government’s priorities:

Steve Paikin: Honestly, honestly, how high up the ladder are cultural institutions in the Minster of Finance’s play-book?’

Greg Sorbara: During my time they were really high up.

SP: They’re not education, and they’re not health care.

GB: You know what, they are what creates a healthy city and they are the way in which we educate ourselves. But the fact is, the future of this city and of this region is in arts and creativity and the production of those arts and the dissemination of that creativity. (Mp3 at 14:50)

Sobera’s answer was wonderful, but I think it could have also been answered this way: ‘what’s the point of having health care and education if you’re going to spend your life bored?’

Daniel Richler once described Mike Harris and Ralph Klein as examples of educational failure, and since hearing him say that 3 I’ve always kept that in mind. The people who Marni Soupcoff is pandering to are educational failures. I don’t care what kind of credentials an MBA or the like amounts to if your indifference to the arts has become openly hostile, and if you’re prone to use words like ‘loser’ when thinking of them. If that’s the case, your education has been no such thing. If you managed to go to university, you paid for your job training and partially subsidized your voluntary lobotomization. An educated person can be indifferent to the arts, but they should at least recognize their value.

As I’ve written, I’m not that much of a fan of the arts-councils. But I support public funding of culture. I just think the process could use reformation. If the Canadian Council was able to fund Soupcoff to go on a self-education sabbatical during which she expose herself to what the best of human beings have been able to achieve, perhaps she might be grateful. However, you can lead the horse to water, but you can’t make them drink. Or, as I’ve heard recently, ‘you can cure ignorance but you can’t cure stupid’.

I’d like to see politicians and journalists start pandering to this societies’ educated rather than to its stupid.

__________________

1. Chapterhouse Dune, 1985, p. 119

2. My position is that the democratic deficit is to blame for increasing violence: governance is disconnected from the citizens who want more social services and less military spending.

3. On the defunct CBC Friday night program out of Vancouver; name of which I don’t remember, circa 2002

I’d rather visit here:

(From, Via)

then here:

(From)

For one, I imagine the first would have a fantastic library.

Although the second is my desktop at work,

The first is my desktop at home.

Fuck Shanghai.

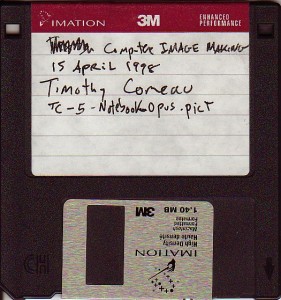

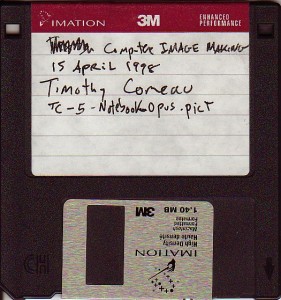

Used for my NSCAD Photoshop class.

Macintosh pre-formated.

Also on Flickr

I’ve come to realize that the CBC is obsolete, and all the fuss and bother about classical music ‘disappearing’ from CBC 2 is pointless. I listen to classical on the net all the time. I prefer it actually, since I can do without the CBC hosts. (That promo guy they have on now drives me nuts; not to mention all the other falsely enthusiastic banter).

For the past two days this is what I listened to at work:

http://www.icebergradio.com/ – classical section, baroque and renaissance.

I’ve been sympathetic to Russell Smith’s defense of CBC 2 in his Globe column over the past couple of years, even bringing up his arguments to a CBC employee I once knew.

Marc Weisblott, in reviewing this for his latest ‘Scrolling Eye’ post on the Eye website, writes

What [Russell Smith] said during a debate on CBC Radio One’s The Current on Wednesday was a bit more nuanced, though, advocating radio for “the sensitive kid bored by the beer-drinking frat culture” like he was. “There are hundreds of thousands of emo kids, and underprivileged kids, around the country who need an escape from the boredom of the bored mass culture around them.”

But, when those proverbial emo kids have never touched a terrestrial radio in their lives, the only place to turn is to the vitriolic greybeards.

…Exactly. I was one of those sensitive kids bored then & now by frat culture, and that’s why I listened to CBC 2. But I’m dismayed to find the same voices on it that were there when I was a child (Jurgen Gothe, I’m thinking of you, and wish you well in your upcoming retirement).

The internet is now there for curious and sensitive youth. With regard to classical, I tend to use Wikipedia to find a location to download it from when I want something for the iPod. The only way Smith’s argument stands up for me is to consider sensitive bored kids using dial-up on the Prairie. In that case, one should bring the protests to the likes of Bell, who’ve begun throttling bandwidth.

To remain relevant to the 21st Century, the CBC should become an ISP, and primarily focus on net streams. Radio should be so old hat to them they could afford to treat it as an afterthought. The situation at the present moment is the reverse. While they did revamp their website last fall, they are still focused on using Windows Media Player, still being stingy with MP3 downloads and podcasting, and still have a stream which is prone to buffering errors.

I get the message, and the message I have in return is

Fuck you too CBC 2.

(On Akimbo)

Well, there’s always next year’s surplus.

And consider this:

“Why weren’t these surplus monies given to the arts councils?”

perhaps to

“end the backroom deals” conducted by “the community review and peer assessment”

If you think the government is corrupted by back-room deals, what would it need to do to prove otherwise? Could such a test be passed by ‘community review and a peer assessment’ organizations? The whole point of ‘peer review’ is to build bias into the system in order to favour applicants (this is why it’s an important part of the judiciary – so that in ancient (and contemporary) times, the burden of proof for a criminal charge had to overcome the bias of a jury of peers. And why O.J. Simpson got away with murder: because a jury of his peers decided that burden of proof had not been met, a decision that had to stand because of the nature of the process).

Perhaps the gov thinks

‘enough is enough’ , ie. they perhaps think there are giving enough already.

But then again, there’s always next year. Perhaps Clive Robertson and Vera Frankel should begin a whitepaper to outline why the monies are needed, and what could be done with them. The older I get the more I become sensitive to arguments about responsibility. I ask the following rhetorically: Why should artists assume they are owed a living by society?

I recently heard something like this said by a right-wing pundit: ‘that people shouldn’t assume they are owed a living by society’. I don’t agree, but am not sure at this point what an appropriate counter-argument could be. The right-wingers would have everyone be responsible and manage their money carefully and aim to be self-sufficient. The Amish are probably an ideal here: they’re so excellent at managing money that they refuse all government assistance. They don’t need it. They’re also so self-sufficient they can afford to turn their backs on contemporary society.

I for one don’t appreciate the idea that because some people are fuck-ups and waste money on drugs or MFA degrees that means they should be condemned to poverty and social exclusion. I hate the idea of punishment in all its forms, and this attitude of letting fuck-ups suffer as homeless or whatever I don’t want to support.

That being said, it is a red flag for artists to demand more money. “Why are they not self-sufficient?” This is certainly a valid question concerning how many artists have turned they’re backs to soceity. If you want to be like the Amish, then figure out how to get by without government funds.

We’ve had year after year of being told artists are important for society, but where is the evidence for that? I see grants being used for projects that are more attuned to ‘personal development’ than that of society. This then raises the question of fairness and responsibility: why should artists get grant money to pay the rent while x & y have to work shitty/boring/whatever jobs?

Whenever I talk with artists about applying for grants, they’re always stressed about how to do their write-ups for whatever project which is just a front for them to get three months of rent and grocery money.

Let’s just be honest and ask that the Provincial Government to create a ‘creative subsidy’ so that individuals who are creative can afford regular ‘sabbaticals’. We might as well lobby Richard Florida (since everyone in a Moores suit cares what he thinks) to include a chapter in his next book (to be on indie music) on the need to have time off – weeks, months, or years, during which one is free to stay up all night, or lay around stoned for 48 hours, or spend afternoons at the library. In some of the later texts of Richard Rorty, he wrote about academics’ need to write up their own grants in order to get time off to unwind, recharge, and read. The sabbatical is cherished part of a creative life, and if you want to lobby for more funding, this is what you want to lobby for – a subsidy for the creative to take time off.

So, getting back to this poster: the Ontario Government helped out institutions who are now better positioned to support the creatives within the community. Boo-hoo. They want the backroom deals to favour them directly, not the only market for their type of art. Whan whan.

(From)

[From Goodreads 08w14:4]

Honestly, if a business can’t afford to pay all its employees a livable wage, than that business should be considered a fail. What are businesses for? (The wrong answer is to say the enrichment of the owners at the expense of the employees, because that’s like Marxism or something, and we’re supposed to be past all that).

I remember when I was working for a minimum wage in Halifax, feeling both totally exploited and humiliated into enforced poverty. Further, the business had like 6 people on the payroll when it only really needed three. That’s where I got the idea that mismanagement should never be an excuse to pay people peanuts. And why I have no sympathy for the business owners who claim raising the minimum wage would be too hard on them. They’re not paying themselves a minimum wage are they?

My greater concern for raising the minimum wage is this society’s capacity to maintain an unfair status quo. As is pointed out in this article, adjusted for inflation, today’s Ontario minimum wage is equivalent to what it was thirteen years ago. I’ve noticed in the past that whenever the minimum wage goes up, so do the prices at Tim Hortons, (which I consider to be an unofficial index of inflation). So the gains of the working poor are immediately offset to erase them. The article begins by pointing out that the Ontario minimum wage went up last week. This week Tim Hortons had signs at its counters saying the prices of some menu items would rise next week. Two weeks ago, the Go Train commuter system rose its ticket prices too.

So, in 2010, when the minimum wage rises to $10 and hour, count on 1.60 coffees (rather than the current 1.42 lg) at your national coffee chain, and corresponding ticket prices across our belle province and sun-shiny country. – Timothy

A dream of a clone of Axel Rose releasing Chinese Democracy, and starting to tour it, when the REAL Axel Rose attacks him on stage, gripping him in a headlock and harrangues the clone and the audience, saying ‘the record isn’t fucking ready yet’.

•Rainy Spring days call forth Nirvana from the playlists; angry Kurt Cobains yell through headphones to say, this was the season when my sadness and alienation and stomach condition became all too much. I’ll never have an email address and I won’t know what the fuck a google is. My songs will live forever on compact discs and cassette tapes, I don’t understand what you mean by iTunes and iPods.

By age 28 I looked out onto a world through eyes that had seen more life than the hurt voice on the playlists. By 33 I’d had beer with a fellow who followed Cobain’s example by rounding off his 29 years with a sleep, bookending my own experience with the extra two years on either end. What is life beyond a mindstream experiencing sense impressions? The gossamer thoughts between the ears, the holograms of remembered scenes beyind the eyes, and the occasional flood of music to soup it up. And for some, the movie ends quicker, the awareness peeling itself away from the inside of the skull and walking into a sunny parking lot to find the car.

Kurt Cobain passes out in with noise and a hurt head. This is beyond the temporary amnesia of a concussion, for he comes to having forgoten everything, including where he left his body. He now finds himself a baby, then a child, and now is suffering through school, aged about thirteen. Perhaps now he is a girl? This teenager’s bedroom is covered in posters of rockstars, and perhaps there is a Niravana poster there as well? This Kurt-tulku thinks Kurt Cobain rocked, complelty oblivious to the fact that he’s the same mind. But this is to speculate on something unpredicatable.

Perhaps he’s a pigeon, a dog, your gerbil, or a cat. Perhaps he became a salmon and was eaten in a resaturant.

But in my imagination, this Kurt kid is starting a high school band, discovering he has a fucking great talent for music.