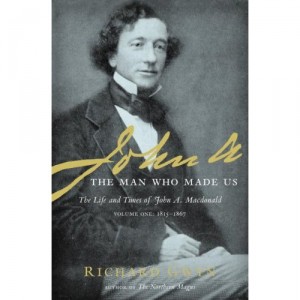

From Richard Gwyn’s John A. Macdonald

In writing this book, I have made a host of spelling “mistakes”, but have paid them no heed. Each has been signaled clearly by a red line that my computer’s U.S. text system inserts beneath the offending word. The mistakes aren’t really mine, though; they are Macdonald’s. He had an order-in-council passed directing that the government’s papers be written in the British style, as with “labour” rather than “labor”.

(p66) In 19C Canada, the observation that all politics is local would have been treated not as insight but as a banality. With occasional exception, such as the campaign to achieve Responsible Government by Population, almost all politics was about local issues. Debates that engaged the general public were almost always those inspired by sectarianism – French vs English, Catholic vs Protestant, and sometime Protestant vs Protestant, as between Anglicans and Methodists. Just about the only non-religious exception to the rule was the issue of Anti-Americanism; it was both widespread and, as was truly rare, a political conviction that promoted national unity because it was held as strongly by the French and by the English.

Almost all politics was local for the simple reason that almost everyone in Canada was a local: at least 80% of Canadians were farmers or independent fishermen. Moreover, they were self-sufficient farmers. They built their own houses. They carved out most of their implements and equipment. They grew almost all their own food (tea and sugar excepted) or raised it on the hoof. They made most of their own clothes. They made their own candles and soap. Among the few products they sold into commercial markets were grain and potash. Few sent their children to school. They were unprotected by policemen (even in the towns in Upper Canada, police forces dates only from the 1840s). For lack of ministers and priests, marriages were often performed by the people themselves. Even the term ‘local’ conveys a false impression of community: roads were so bad and farms spaced so far apart that social contact was limited principally to ‘bees’ – barn and house raising, stump clearing and later, more fancifully, quilting.

Government’s reach in Canada was markedly more stunted than in England. While there had been a Poor Law there from 1597, the first statute of the Legislature of Upper Canada provided specifically that ‘Nothing in this Act … shall introduce any of the laws of England concerning the maintenance of the poor’. (The Maritimes, then quite separate colonies, had both Poor Laws and Poor Houses). The churches were responsible for charity, and in some areas for education (The first legislation in British North America to establish free education was in Prince Edward Island in 1852. Nova Scotia followed in 1864, and Ontario only after Confederation). It was the same for that other form of social activism, the Temperance Societies, commonly brought into being by the Methodist, Presbyterian and Baptist churches. The unemployed were ‘the idle poor,’ and no government had any notion that it should be responsible for their succor. Governments collected taxes (almost exclusively customs and excise duties) and were responsible for law and order, maintaing the militia, and running the jails, where the idea of rehabilitation as opposed to punishment was unknown. But without income tax, there was comparatively little the government could do even if it wished. Consequently, the total spending on public charities, social programs and education amounted to just 9% of any government’s revenues. To most Canadians in the middle of the 19C, government was irrelevant to their day to day lives as it is today to the Mennonites, Hutterites and Amish.

[…] In mid to late 19C Canada, conservatism was as widely held a political attitude as liberalism would become a century later. It took a long while for things to change. In one post-Confederation debated, in 1876, held during an economic depression, a Liberal MP argued that the government should assist the poor. Another MP rounded on him to declare “The moment a Government is asked to take charge and feed the poor you strike a blow to their self-respect and independence that is fatal to our existence as a people.’ The shocked intervenor was also a Liberal, as was the government of the day.

Amid this emphasis on the local, there was, nevertheless, one broad national dimension. Governments were remarkably ready to go into debt – proportionally more deeply than today – to build up the nation itself. Here, Conservatives were actually greater risk-takers than the Reformers. Bishop Joseph Strachan, a leading member of the arch-conservative Family Compact, held that ‘the existence of a national debt may be perfectly consistent with the interests and prosperity of the Country’. In the early and middle part of the century, mostly Conservative governments bankrolled major public projects – first canals, such as the Welland, the Lachine and the Rideau – and then a spiderweb of railways, nearly all of them money-losing. The Conservatives were, of course, undertaking projects that benefited their supporters, but they were also building the country. [… p 69]

p. 89 A great many Canadians have come to assume that their country began on July 1 1867, not least because we celebrate each year the anniversary of Confederation. But Confederation wasn’t the starting point of all that we no have and are. It developed from its own past, and that past, even if now far distant from us, still materially affects our present and our future.

The most explicit description of the continuity of Canadian politics across the centuries is made by historian Gordon Stewart in his book The Origins of Canadian Politics. There he writes, “The key to understanding the main features of Canadian national political culture after 1867 lies in the political world of Upper and Lower Canada between 1790s and the 1860s.” His argument, one shared fully by the author, is that all Canadian politics, even those in our postmodern, high-tech, 21st Century present, have been influenced substantively by events and attitudes in the horse-and-buggy Canada of our dim past.

[…]

The catalyst of fundamental change in pre-Confederation politics were the rebellions in 1837-38 by the Patriotes in Lower Canada led by Louis-Joseph Papineau, which was a serious uprising, and by the rebels in Upper Canada led by William Lyon Mackenzie, which was more of a tragicomedy. Both uprisings provided a warning to London that, as had gone the American colonies a half-century earlier, so the colonies of British North America might also go. To deal with the crisis, the Imperial government sent out one of its best and brightest.

John George Lambton, Earl of Durham, arrived accompanied by an orchestra, several race horses, a full complement of silver and a cluster of brainy aides, one of whom had achieved celebrity status by running off with a teenage heiress and serving time briefly in jail. Still in his early forties, ‘Radical Jack’ was cerebral, cold, acerbic and arrogant. After just five months in the colony, he left in a rage after a decision of his – to exile many of the Patriotes to Bermuda without the bother of a trial – was countermanded by the Colonial Office. Back home, he completed, in 1839, a report that was perhaps the single most important public document in all Canadian history. Lord Durham himself died of TB a year later.

Parts of Durham’s report were brilliant; parts were brutal. The effects of each were identical: they both had an extraordinarily creative effect on Canada and Canadians. The brutal parts of Durham’s diagnosis are, as almost always happens, much the better known. He had found here, he declared, “two nations warring in the bosom of a single state … a struggle, not to principles, but of races (Durham’s use of the word ‘race’ will strike contemporary [readers] as odd. It was used then to describe people now usually referred to as ‘ethnic groups’.) The French Canadians, les Canadiens, had to lose – for their own sake. They were ‘a people destitute of all that could constitute a nationality … brood[ing] in sullen silence over the memory of their fallen countrymen, of their burnt villages, of their ruined property, of their extinguished ascendancy.’

In fact, Durham was almost as hard about the English in Canada. They were ‘hardly better off than the French for their means of education for their children.’ They were almost as indolent: ‘On the American side, all is activity and hustle … On the British side of the line, except for a few favoured spots, all seems waste and desolate.’ He dismissed the powerful Family Compact as ‘these wretches’. Still, he took it for granted that Anglo-Saxons would dominate the French majority in their own Lower Canada. ‘The entire wholesale and a large portion of the retail trade of the Province, with the most profitable and flourishing farms, are now in the hands of this dominant minority.’ All French Canadians could do was ‘look upon their rivals with alarm, with jealousy, and finally with hatred.’

The only way to end this perpetual clash between the ‘races’ Durham concluded, was there to be just one race in Canada. The two separate, ethnically defined provinces of Upper Canada and Lower Canada should be combined into the United Province of Canada. As immigrants poured in from the British Isles, the French would inevitably become a minority. To quicken the pace of assimilation, the use of French should cease in the new, single legislature and government. To minimize the political weight of Lower Canada 650,000 people, compared with Upper Canada’s 450,000 each former province, now reduced to a ‘section’ should have an equal number of members in the new legislature. (Officially, Upper Canada now became Canada West, and Lower Canada became Canada East. In fact, almost everyone continued to refer to the new sections by their old titles … In fact, the legislature re-legalized the use of the old Upper and Lower Canada terms in 1849).

Durham’s formula worked – but backwards. Quebec’s commitment to la survivance dates less from Wolfe’s victory over Montcalm [in 17x] (after which the Canadiens’ religions and system of low were protected by British decree) than from 1839, when Durham told French Canadians they were finished. The consequences of this collective death sentence was an incredible flowering of a national will to remain alive. (A parallel exists with the publication in 1965 of George Grant’s Lament for a Nation predicting Canada’s inevitable absorption by America. In response, English-Canadian nationalists suddenly stood on guard for their country).

[…]

Few in Upper Canada noticed [the flowering of French-Canadian self-awareness]. Their attention was focused on the other part of Durham’s report, one calling for a totally different kind of Parliament. It was to be a responsible Parliament, with a cabinet composed of member of the majority party rather than chose at the pleasure of the governor general. In a phrase of almost breathtaking boldness, Durham wrote, ‘The British people of the North American Colonies are a a people on whom we may safely rely, and to whom we must not grudge power.’

– Richard Gwyn, John A. Macdonald Vol I 2007