Lauren Zalaznick

Lauren Zalaznick in her 30 Rockerfeller Plaza office.

From The New York Times Magazine

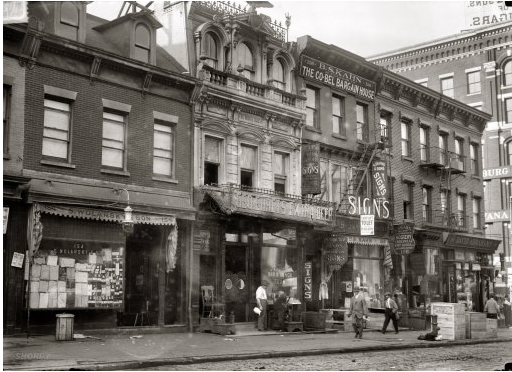

156 Canal St circa 2008 from Google Maps Streetview

In alphabetical order –

Harper C Party: I’m not ideological enough to be scared by Harper. More or less I find him uninspiring and disappointing. I think the Conservative strength is in their fiscal policy: I for one am looking forward to opening one of their registered savings accounts in January. But money matters are not inspiring matters, and when their cuts about arts created an uproar, the question shifted to not whether they were justified or not, but to the perception that the Conservatives don’t care about culture. Mr. Harper positively beamed when talking about the talents of his kids. He’s a proud father. It is striking that the question was even asked – when was the last time arts-n-culture were part of an electoral campaign?

I’ve admitted in the past that I respect Mr. Harper. I like the no-nonsense attitude, yes. But I’ll never vote conservative for as long as I live, and that has everything to do with their hard-hardheartedness. Maybe I respect Harper because he comes across as the only intelligent one of the bunch. He’s not a windbag like Jason Kenney, nor as much of an unprofessional jerk like Jim ‘don’t invest in Ontario’ Flaherty – a stinky old fish from the Harris regime (which John Ralston Saul described as ‘intentionally evil’ in his new book, writing about their attacks on the school system). At my riding’s All Candidates Meeting, Gerrard Kennedy tried to scare-monger by describing Harper as Harris. Puhlease. Harris was a typical stupid bully, whereas Harper is just the self-righteous smart kid who gets great grades and makes everyone feel bad. There’s a big difference. It is notable that they gravitated to the same political spectrum however.

Underlying conservative arguments is a not only past-oriented romanticism, but also an ignorance which feeds bigotry. They are ultimately the party of stupid patriarchs, and we’ve had quite enough of that.

The Conservatives display financial expertise. But it seems to be the only thing they can speak about with authority. Since life is about more than money, I’d appreciate more well-rounded fuck-saying people in my government.

Day – G-Party: Ms. Day was fantastic, bringing up obscure facts to educate the public on. I’m increasingly thinking I may vote Green. That’s all I need to say I think. I hope she impressed many people to do the same.

Dion L-Party: Mr. Dion spoke with authority, but what an uphill battle. He cowered for the past 18 months since becoming leader, and when the election was called brought up the fact that Harper was violating his own fixed-election date law. WTF? I mean seriously, what … the … fuck !??? You mean to tell me the reason we haven’t had his election sooner was because Dion seriously respected that silly law, which is obviously of no consequence? Does he really want to be PM? You mean, he would have contently waited out his role as leader of the Opp with the calendar marked with Harper’s fixed-election date? God I wish they’d made Ignatieff leader when they had the chance.

Besides that, Green Shift … whatever. I don’t care what it’s called or what it costs, I want to be able to breath outside when I’m 90. All parties seem to agree on this except for the stupid Conservatives.

Layton – N Party: Layton did a good job of agreeing with Day. That wasn’t a bad thing, since it reflected sensibility. Jack Layton isn’t someone I have any big problems with, and he’d make an excellent Prime Minister. The NDP tend to seem shifty because they come across as impractical (vs. the Conservative practicality). He made a good point in suggesting that if citizens want a better government, they should try electing one which doesn’t start with an L or a C (not his words, my interpretation). I would like to see the NDP appear more well-rounded and stop catering to relatively minor issues like fucking bank fees. I mean, banks suck of course, but I don’t need the leader of the minority opposition treating it like a mission more important than child care and health care and all the rest. The NDP have done a great job in keeping the Conservative budgets from being overly-crazy, and I commend them on that.

Duceppe – Q Party: Duceppe was irrelevant to English Canada.

Democracy is an open source project. You can quote me on that.

Ok, I will.

“Paying for things is our way of compensating all the people who have been inconvenienced by our consumption. (Next time you buy a cup of coffee at Starbucks, imagine yourself saying to the barista, ‘I’m sorry that you had to serve me coffee when you could have been doing other things. And please communicate my apologies to the others as well: the owner, the landlord, the shipping company, the Columbian peasants. Here’s $1.75 for all the trouble. Please divide it among yourselves.’)”

– Joseph Heath, ‘Filthy Lucre’ (2009) p. 160

I drafted the majority of this a couple of weeks ago, in light of the recent announcement of the funding cuts. In the interim weeks, Leah Sandals and Jennifer McMackon have done better jobs than I could have in assembling related links. Also, in the past week, it became increasingly clear that Harper will call an election within the next two weeks, making these controversial cuts and copyright bill null and void unless the Conservatives return to power with another minority or, god help us, a majority.

I live in a riding with an NDP candidate, and I will with good conscious vote to reelect her. Doubly, as a citizen of Toronto, I’m in an essentially Liberal area. For this reason, it has been said over the previous two and half years (since the last election) that the Conservatives have been screwing us over. It has also been said that Harper ideally wants to destroy the Liberal party. Do we really want to have such a petty and vindictive bunch of assholes deciding things for the other 33 million of us? Equally troubling is the fact that Harper grew up in Etobicoke, which is to say, Harper hates his home town. Well, fuck him too, and the scare-mongering flyers I’ve been receiving in my mailbox.

To Take Care of Oneself

As artists, it’s not a question that society owes us a living; to use that phrase is itself problematic – to say use the word owe, suggesting a debt or some other economic transaction.

For me, I go back to my early 20s, having gone through art school and having met and befriended people who in many ways weren’t really capable of taking care of themselves. They were deficient in life skills primarily, but also in terms of coping mechanisms. It wasn’t so much that they were losers or retarded in the legitimate sense of the word, but they were just different, round pegs for society’s square holes. Myself, I’d like to live in a society of difference/variety/heterogeneity. How we deal with the challenges presented by ‘un-normal’ people is one by which we can measure the state of our civilization. Since for me civilization is about the education we provide and acquire to remove ourselves as far as possible from the states of animals (who are fearful, ignorant and cruel), a civilized society is one reflective of communities of care and of elevated compassion: a state present even in animals but which we can nurture and encourage more of as self-aware beings.

In grade school, we had a class of ‘special kids’ who were the ones in wheelchairs, or were borderline blind, or whatever. One girl in particular I remember as probably having cerebral palsy. Because of the area (rural Nova Scotia) this class might have been doubling as a day care (I’m not sure what type of education was being provided) but for the most part, adapting to the needs of these children was taken for granted as the proper thing to do. It taught me that I lived in a civilized society because these people were both cared for and not to be mocked. Through this a sense of compassion was both taught and encouraged.

In my 20s, I learned that some people weren’t able to take care of themselves. And the lesson for me was just because this is so doesn’t mean people should be poor, unemployable and underemployed, nor end up homeless. It should be possible to accept these people and make sure they have homes, enough money for food and clothing and comfortable lives. There’s no need for them to suffer just because they’re different.

Like the disabled children of my community, they should to be taken care of. As a rich society not overwhelmed by the incompetent (I’d guess they’re less than 20% of the population), it should cost peanuts to make sure these people have ok lives. Considering that the real fuck-ups who end of in jail are cared for by the state, investing in keeping the annoying from becoming homeless and moochy shouldn’t be that big of a deal.

Maybe all they need is some kind of compassionate service – a councilor or a social worker. In terms of homelessness explicitly, I’ve heard it said that many are people who would be fine if they had a stable address and a social worker to help them take their medications on time. This doesn’t seem a lot to ask. If we can provide services for those who are not able-bodied, we should also accept that some people are just born different, and that they are just not ‘able-minded’ by what are thought of as society’s norms. 1

There is room for critique as to what constitutes the able-minded, but that is for another discussion. Meanwhile we’ve had plenty of critique of society’s norms, and while that has brought to light these considerations, they haven’t done much to encourage people toward compassion.

People who aren’t capable of fitting-in (to the extent that they can’t take care of themselves in the usually accepted way) just need accommodation and consideration. It isn’t a question of being owed, but of helping people within our community. Those who are physically and congenitally disadvantaged do not argue about being owed a living, but I think they rightfully feel entitled to being treated with respect and dignity.

So, send in the artists, with century old arguments about being owed a living and expecting support from government-funded organizations. What these arguments amount to is artists saying they’re retards who can’t take care of themselves and are essentially hopeless at basic economic management. Given that it was in art school that I began to think about this (as stated), that may be case. However, unlike the trolls commenting on the newspaper-site boards, who are happy with the cuts, I didn’t consider my fellow art-students and graduated artists as losers, but simply different. And so, I’m not very sympathetic to a line of argument that plays into ignorant prejudice among those completely uneducated and insensitive to the arts. The continued begging at government coffers, based on the idea that artists are incapable of surviving without it, seems self-harming and essentially untrue.

On the one hand, artists like to argue that they’re vital to society for all sorts of reasons, but on the other hand, they’re arguing that they’re incapable of functioning within that society. Over here, arguments about the intelligence of art and the superiority of the artist over the corporate clerk, and over there, whining about capitalist exploitation in the Third World while their dealers take 50% of the price of their work. Here a sense of entitlement to government financing, while there, artists who want to be above regulation and censorship while continuing to cash the government cheques.

In a sense, artists have become the ill character of a sitcom who doesn’t want to get better because everyone has become kind and giving toward them. In that manner they’ve degraded themselves and have invited disdain, which by the end of the episode is played for laughs. One of the values of Conservatives is personal responsibility, and the ability to take care of oneself. It thus follows that Conservative governments do not see much value in funding the arts because it’s representative of coddling adults who should be able to self-manage. By arguing that they’re retarded for so long, artists have willfully invited disdain.

Canada is a hard place to live

Sixty years ago, Roberston Davies’ Fortune, My Foe was first performed in Kingston. It contains a line I’ve seen much quoted in arguments reflecting on the development of arts funding in Canada.

Everybody says Canada is a hard country to govern, but nobody mentions that for some people it is also a hard country to live in. Still, if we all run away it will never be any better. So let the geniuses of easy virtue go southward; I know what they feel too well to blame them. But for some of us there is no choice; let Canada do what she will with us, we must stay.

Davies of course did not leave, but stayed and became part of the Canadian cultural legacy. (The internationalism of the film/television and music industries meant that we can still lay claim to those stars who now live elsewhere but who began with Canadian passports). In the years leading up to the 1967 Centenary, Canadians (reflecting a post-war, mid-20th Century modernist mindset as much as anything else) invested in developing a sense of nationalism. The result of this investment is people like John Ralston Saul and Adrienne Clarkson, the only two Canadians left in the media-scape praising Canada as a nation, both old enough to have been young adults at the Centenary, and both now at an age when they just seem like old fuddy-duddies.

The children of their generation is that of my own, kids born in the ’60s and ’70s and in terms of inherited legacies, pot smoking was far more successfully passed on then the spirit of Canadian nationalism. Planted in post-war soil Canadian Nationalism flowered for 1967, was worn in the lapel of Trudeau, then withered and died as is natural for flowers and all other living things. While ambitious and certainly worth the attempt, a government funded attempt at generating an artificial trans-continental consciousness in a place so geographically varied and multicultural is retrospectively absurd and perhaps deserving of it’s demise.

But the 1950s research into this attempt was that of the Massey Commission and the result was the Canada Council. We are told legends by elders of generous funding and ‘National Gallery Biennials’, where every couple of years the National Gallery would ‘define where Canadian art was at’. (src). This was part of the Nationalistic enculturation which produced the likes of Saul and Clarkson. By this early 21st Century, the children of those boomers are much more interested in city-state politics and thinking, founding the likes of Spacing magazine, not really giving a shit about McCleans while mocking Richard Florida even as he legitimizes them to the current crop of out-of-touch establishment.

In his 1993 introduction to a reprint of Fortune my Foe, Davies describes the genesis of the play; after World War II put a stop to touring plays by independent and occasionally American theatre companies, his university friend Arthur Sutherland established a theatre company in Kingston and invited Davies to write a ‘Canadian’ play to complement the repertoire of English and American comedies. In describing this background, Davies defines an artist as ‘a person who enlarges and illuminates the lives of others.’ In commissioning a young Roberston Davies, Sutherland, although aware of the risk…

“…wanted a play about Canada. It was risky because Canada has for a long time been thought a dull country, with dull people. But there was a time when Norway was thought dull, and Ireland was thought absurd, yet both of them brought forth plays which have been acclaimed as treasures by theatres around the world.”

Which reminds me of Norman Mailer’s claim that the economic recovery of Ireland in recent years can be traced to James Joyce. In other words, the capacity of a country to see itself reflected in a work of imagination can both be an ‘enlarging’ experience and also so inspiring to bind a community together. Davies is also claiming that the difference between being considered dull and ‘interesting’ (or cool, in the present sense) is in the nature of one’s self-imagining, and the messages that puts out. If painters of the United States had confined themselves to images of the American Gothic and considered that an accurate self-representation rather than satire, would we not think of the U.S. as dull?

After offering a synopsis of his play, Davies in the ’93 introduction goes on to say that his task was to make the play not too didactic. Within the structure of the play Davies had a character of a puppeteer, a European immigrant, who is sponsored to give a puppet show by the producer characters of Philpott and Tapscott. As Davies explains, the European puppet master was reflective of the recent wave of European immigrants and refugees from devastated Europe, who brought with them Old World sensibilities about art and culture, and were met with a homegrown New World audience who did not share those same ideas.

“Message,” Davies wrote, “was very much on the lips of Canadians like Philpott and Tapscott, the do-gooders who took up the puppet-show, without having any understanding of its special quality or its cultural background, but who were convinced that the task of art was to teach – to offer a Message, in fact, and to offer it in terms that the stupidest listener could understand. Canada was, and still is, full of such people. They think of art of all kinds as a sort of handmaid to education; it must have a Message and it must get across. The truth is that art does not teach; it makes you feel, and any teaching that may arise from the feeling is an extra, and must not be stressed too much. In the modern world, and in Canada as much as anywhere, we are obsessed with the notion that to think is the highest achievement of mankind, but we neglect the fact that thought untouched by feeling is thin, delusive, treacherous stuff”.

Is it not the idea that the Conservatives, in government and individually, are people not touched by feeling? Is this not reflected in Jose Verner’s comments that she would like cultural funding to be efficient? Myself, I like efficiency since it’s about doing as much as possible with the least effort – in other words, ‘being lazy is good’ as they say in computer programing, for just this reason.

It is in fact sensible for the government to want to do this. But it is also the case that the government appears to show a disdain for the arts that lie partially in a complacency engendered by funding. Canadian art is rather pathetic and remains so because the infrastructure was set up within a moment of forethought and generosity, and instead of igniting both the imagination and the culture of the country, merely created institutions staffed by people who take the funding for granted and feel entitled within their institutional titles. Instead of fostering culture, they see themselves as beyond petty and quaint nationalistic concerns and instead fly off to Venice every couple of years to hob-nob with the planet’s remaining arrogant aristocrats, shaking away the dirt of the stupid ‘unwashed masses’ of this country who usually live in the neighborhoods the galleries move to. Admittedly, that’s being overly cynical and ignoring the good that many artist-run centres and other galleries do within their neighborhoods (before raising the market-value of neighboring properties by their presence) but such ‘good’ is questionable as a repetition of a colonial mindset that sees certain groups as needing help: bring them civilization and culture; capital-c Culture having replaced Jesus in a secular society.

On July 17th I had no idea that the programs in question even existed, and I’m in the culture business. Which is to say that the gang of young adults who have turned Toronto’s gallery-area Queen West West into another nightclub district probably have never heard of the programs either. Why then should I or they have cared on August 17th? When I didn’t know they existed I didn’t care, and now that I know they exist and may not for much longer I still don’t care that much. In effect, the Conservatives have potentially legislated my mid-July mindset into existence.

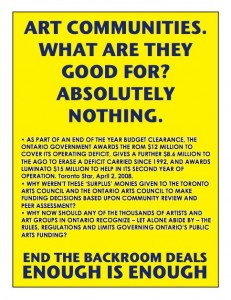

In as much as I’ve gotten emails repeating the contents of a new Facebook group, I have a suspicion this may be a lost cause. As evinced by their artist-statements, artists in this country are rarely capable of being eloquent enough to convince Conservatives or the rest of the population of their value. The Conservatives have upset an easily ignored minority, and inspired such comments as:

“when the government stops spending money on endeavours that provide next to no value to the Canadian people it is not pandering, it is good government. Am I the only person in the god forsaken country that remembers we have a fricking health care crisis? Sure, there is an element of pandering, and there is plenty of other funding that should be pulled but will not be, but the simple act of pulling funding from people who never should have received it is a good thing. End of story.” (from)

and

“I think that is what I was getting at. I’m all for supporting the arts but I feel that people of Mr. Lewis’s status and influence should not be receiving money from the government whether he is right or left wing. A friend of mine is an artist and she maintains most of the arts grants go to people who don’t need them. The real starving artists don’t have the influence to affect awards.” (from)

and

“The government is the one entity in the country that is least likely to make an intelligent decision on how to spend money. In fact, the only reasons to access government funding over private are laziness, a desire to be unaccountable for the funds you receive, and the knowledge that the general public sees no value in your product.

The government should contribute to the arts through tax credits alone. This can amount to a large amount of support, ensures there will be a respectable amount of accountability built into the system, and will bring the arts community closer to the community it supposedly serves.” (from)

yet, there is one considered argument:

“Fund the Olympics and not artists? Artists leave something behind for future generations; athletes… well, they’re fun to watch. Someone said independent producers such as Avi Lewis should pay to find their own distributors. Maybe. But then you should be consistent and argue against ALL government economic subsidies and incentives. Let’s stop subsidizing automakers, oil companies, the aerospace industry, etc. For the most part, the organizations and individuals affected here are either completely non-ideological (such as Tafelmusik) or engaging in economic development for Canadian businesses, which employ Canadians (such as the Hot Docs festival’s Toronto Documentary Forum, which among other things, brings foreign investment into Canadian productions). Finally, what’s lost here is that arts and culture have always been an important part of international diplomacy. The Tories are letting their ideology trump the national interest. Shame on them.” (from)

But in regards to Tafelmusik, a baroque orchestra playing on period instruments, they charge between $89 to $15 dollars a ticket. Surely they work a profit margin in there somewhere? Surely those wealthy egotists so eager to have their name immortalized for the a decades on a hospital wing (or listed in platinum lettering in the lobby of retarded new ‘expansions’ ignored by people waiting in line to pay $22 to see largely empty galleries) can find a mil or two to send the Bach to China?

[Cross-posted from Goodreads 08w35:2]

Between plane-living and the Internets we may be midway through the process of distilling every place on Earth down to one of a half-dozen archetypal city-states but until that happens trying to affect a person’s relationship to the history and geography of whatever piece of dirt they call home will continue to be a source of tension.

Eighteen city-states within a global Imperial political model = late 21st Century.

I first began hearing the city-state meme in the mid-1990s. An awarness of it, or a tendency to quote it as Aaron Cope has done, is almost a marker of a generation. John Ralston Saul and his wife are part of the last generation of Canadian nationalists, always ready to write books on Canada and to talk about what it means to be Canadian. Meanwhile, people my own age, in my own city, started Spacing magazine, which is very much of the city-state mentality.

I saw the image in the blog posting, positing the fate of one of the characters. Because we know that the story takes place at a post-apocalyptic time, and thinking this was a leaked shot from an upcoming episode, I imagined the wildflowers were those of British Columbia spring, depicting some time in the far-off post-catastrophe future. The camera would rotate about it, there’d be some slow motion fluttering of cloth, angelics and whatever.

Then I Google the file name and find this. Still, on yesterday’s walk, I thought about the wild flowers, the future, and the simplicity of the character’s supposed fate. And made the image my Desktop wallpaper.

Because of the context in which I first encountered it, the image has poetic resonance. But had I found it’s Photoshoped goodness in its original context, I wouldn’t have reason to think differently of wildflowers.

With the exception of the Tragically Hip, I have excluded Canadian musicians simply because they would exaggerate the list and because Canadian music for the most part is no more culturally specific than any other (accounting for its international success). The inclusion of the Hip here reflects their use of Canadian specific content throughout their songs. Leonard Cohen is included for his work as writer more than for his work as a musician.

This list merely tried to illustrate the groupings of artists by generation, to show the progression of cultural achievers over the last century. This illustrates that at the beginning of the 21st Century we have a legacy of artists to understand a heritage around, which wasn’t so much the case even fifty years ago. Also, any name not here is more of an oversight than a judgment (suggestions welcome).

Catharine Parr Traill 1802 – 1899

Susanna Moodie 1803 – 1885

Ozias Leduc 1864-1955

J.E.H. MacDonald 1873 – 1932 (G7)

Tom Thomson 1877-1917 (G7)

Fred Varley 1881-1969 (G7)

A.Y. Jackson 1882-1974 (G7)

Lawren Harris 1885-1970 (G7)

Arthus Lismer 1885-1969 (G7)

Frank Johnston 1888 – 1949 (G7)

Franklin Carmichael 1890 – 1945 (G7)

Harold Innis 1894-1952

Paul-Emile Borduas 1905-1960

Hugh MacLennan 1907-1990

Marshall McLuhan 1911 – 1980

Northrop Frye 1912-1991

Robertson Davies 1913-1995

George Grant 1918-1988

Pierre Trudeau 1919 – 2000

Jean-Paul Riopelle 1923-2002

Oscar Peterson 1925-2007

Margaret Laurence 1926-1987

Timothy Findley 1930 – 2002

Mordecai Richler 1931-2001

Alice Munro 1931 –

Glenn Gould 1932 – 1982

Robert Fulford 1932-

Leonard Cohen 1934 –

Garry Neil Kennedy 1935 –

Margaret Atwood 1939 –

Adrienne Clarkson 1939 –

Jorge Zontal 1944 – 1994 (General Idea)

Felix Partz 1945-1994

Jeff Wall 1946 –

AA Bronson 1946- (General Idea; Solo)

John Ralston Saul 1947 –

Rodney Graham 1949 –

David Gilmour 1949 –

George Elliott Clarke 1960 –

Douglas Coupland 1961 –

Gordon Downie 1964 – (Tragically Hip)

Paul Langlois (1964 – (Tragically Hip)

Rob Baker 1962 (Tragically Hip)

Gord Sinclair (Tragically Hip)

Johnny Fay 1966 – (Tragically Hip)

Mark Kingwell 1965-

Darren O’Donnell 1965 –

(From)

Alpha Beta Gamma

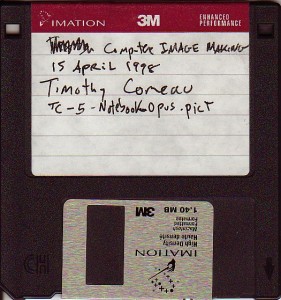

I recently decided that my current website is actually version 5.2, not 4.4. This needs some explaining.

I learned web design through books on the advice of a friend. My first book (Elizabeth Castro’s HTML 4) along with View Source cut-n-paste got me writing my first rudimentary website in 2000. It wasn’t until early 2002 (through Geocities) that I learned how to FTP. It was a proud moment when I was able for the first time to see one of my jpegs on someone else’s computer via the net.

During the summer of 2002, I built my first website. It was hosted on Geocities and later moved to Instant Coffee‘s server.

This went through a number of body-colour variations (and upper-right hand graphics) before it ended up as it remains today.

The Way-Back Machine shows me a site on the Instant Coffee server from February 2003 which I called then Version 4, meaning it was the 4th design revision I’d gone through since the above # 1, before I scrapped all this alpha-draft code later that summer.

When, in August 2003, I tried to apply what I’d learned in the previous year by building my first complicated site, using Youngpup.net‘s ypSlideOutMenus code. This page (as was proper for the time) even had a splash page.

In August 2004, I again worked on redesigning my site, to incorporate what I’d learned in the previous year. This site used CSS and my then basic understanding of PHP Switches and MySql.

I left this site for two years, until August 2006, when I began working on another redesign. However, while I began the basic layout during August, I backburnered it until December, and made it public in January 2007, when I acquired my timothycomeau.com domain name and new server space (until this time, the previous websites had been sub-directories of my host. The 2002-2003 sites had been found at tim.instantcoffee.org or instantcoffee.org/timothy and then the 2004-2006 site had been at goodreads.ca/timothy). For this reason, I sometimes refer to this design as ‘the 2006 one’ or ‘the 2007 one’. I’ve pretty much decided from here on to think of it as ‘the 2006 one’ since that’s how I’ve come to consistently remember it.

Last December I began to redesign the site, to once again update it according to my expanded know-how. Because I felt I’d simply redesigned the menu and updated the logo, I felt that it was a version of #4 (most recently 4.4) and hence, until recently, I’d considered it such. But, I’ve come to think of the present site as a different ‘2008 version’ and figured I should just consider it a #5. Since the .dot numbers come somewhat arbitrarily via whatever small improvements I make here in there, I figured it’s present state is about two modifications away from where it was at in January (when I considered 4.2) hence, version 5.2.

Sometime within the next thirty years, the area of Yonge St incorporating Sam the Record Man, Dundas Square, up to Bloor, will be preserved in all its classless glory as a heritage district of late 20th Century.

My contribution to the book Decentre: concerning artist-run culture/a propos de centres d’artistes published by YYZ Books, and which launches tonight in Toronto.

———————–

Artist-run centres developed to exhibit what at the time was unmarketable, and in so doing became the elitist arbiters of a contemporary taste, based on a reputation for taking risks and initial support of those who went on to become the academics and international art stars (and therefore the default judges of what constitutes good art). Undoubtedly without their presence we’d be culturally poorer, yet today they have become part of an economic system of which they’re in denial.

Because artists have always depended on the patronage of the rich, the artist-run centres have become essential within the overall art system, arguably the only “dealer” that really matters to patrons. To have any sense of artistic legitimacy in Canada – the type that gets you bought by institutions – one needs to somehow be affiliated with an artist-run centre.

Today’s art institution will buy based on a trendiness they equate with aesthetic and cultural merit, and their purchase perpetuates the artist’s delusion that they matter in some grander context, even while their piece lies in a crate in storage. Had they sold to a private patron, they could at least watch as this person re-sells their work to another rich person or to an institution looking for a piece of trendy action on someone once overlooked. The seller does this to a potentially large profit, a share of which the artist won’t see.

Because artist-run centres are staffed by a relatively small network of professionals, they’ve unfortunately become nests of nepotism. How many young artists new to the system send off packages bi-annually only to watch the exhibition calendar fill up with ”curated” shows featuring artists who are friends with staff and board members? This is exacerbated by allegiances to obsolete ideas and aesthetic ideologies which result in shows of boring work weakly justified with poorly written brochure essays.

The fortunate thing is that every five years an artist-run-centre is populated by a new generation of staff, exhibiting artists, and board members. This makes them highly adaptable to changing cultural conditions, and perpetually reformable.

JA: Do you want to add something about the art scene?

RR: I have this vague sense that the art world has become so isolated from everything else in the universe that you’re either in it or in the rest of the world — nobody has time to be in both.

-Josefina Ayerza interviewed Richard Rorty in the Nov/Dec 1993 issue of Flash Art

Moving parts in rubbing contact require lubrication to avoid excessive wear. Honorifics and formal politeness provide lubrication where people rub together. Often the very young, the untraveled, the naive, the unsophisticated deplore these formalities as “empty,” “meaningless,” or “dishonest,” and scorn to use them. No matter how “pure” their motives, they thereby throw sand into machinery that does not work too well at best.

-Robert Heinlein, The Notebooks of Lazarus Long, from Time Enough for Love (1973)

(From Goodreads 08w26:1)

I saw Darren O’Donnell at the Toronto Free Gallery opening last Thursday night and he told me he’d been engaged in the past week with an online debate about the validity of his work with Mammalian Diving Reflex, a debate initiated by Gabriel Moser and picked up on the Sally McKay’/Lorna Mills blog.

I’ve recently moved and had been in no rush to get the net at home set up, a situation further compounded by Rogers’ incompetence (I’m posting this from work dear reader), so this debate had escaped my attention. However, alerted by Darren, I looked up the links at work on Friday and printed off the conversation for some weekend reading. My immediate reaction (especially having converted it to page-length) was ‘wow’ – to the two documents both approximately 20 pages in length. As much as Darren was enervated by the criticism, at least this was a conversation being had.

I met Darren shortly before he began his `social acupuncture` projects, and so I’ve always felt I had an insider’s perspective on them, having participated in and been witness to some of their earlier manifestations. Further, I was at the book launch for his Social Acupuncture (meaning I read it as soon as was possible) and so I have the insight provided by his brilliant essay at the back of my mind with regard to the work.

What Moser and Sandals provide me with is the perspective of someone who doesn’t know Darren personally. Sandals is upfront in admitting she doesn’t like Darren which biases her against the work (src). Another friend of mine admitted that he didn’t quite understand what the work was about art-wise either, but at the time I countered that it was part of our culture’s move away from fiction toward non-fiction (a personal interpretation I worked out somewhat in Goodreads 07w11:1).

I do take issue with one of Moser’s interpretations, since it made me sputter in indignation. I’ve never met Ms. Moser and would like to think we could get along in the future, but I have to nominate one of her paragraphs as one of the stupidest things I’ve ever read.

Speaking of the humor of Mammalian Diving Reflex’s work with children, she wrote:

But the pessimistic part of me thinks that the humour actually lies in something far less self-aware and much more sinister. This part – let’s call it the UBC indoctrinated part – thinks that the humour actually comes from a strange and almost colonial kind of child-adult anthropomorphism. That when adults see these kids trying to play grown up, the humour comes from the fact that we think they’re ‘cute’ in a patronizing way – that their inability to successfully inhabit these [adult] roles is funny in the same way that watching a dog awkwardly dressed in a human business suit is funny.

Anthropomorphism is a completely inappropriate concept to apply to children, suggesting that they aren’t part of our species (only adults are truly human ?) but are akin to dogs dressed up. I am surprised that this thought occurred to her, and doubly surprised that she saw fit to publish it. If only UBC indoctrination had taught her to recognize foolishness when it occasionally occurs, even in the best of minds.

I find nothing humorous about the Mammalian Projects, nor does ‘cute’ really enter into it for me. I’m informed by Darren’s ideas about acupuncture – that you’re poking a dam to hopefully collapse it and return the flow – and in this case, Darren is working with our society’s totally fucked up ideas about children. These ideas are so fucked up that a writer doesn’t recognize how inappropriate it is to use the word ‘anthropomorphic’ when speaking of them.

I keep thinking of a passage from Christopher Alexander’s Pattern Language. In Pattern 57, Children in the City Alexander wrote:

If children are not able to explore the whole of the adult world round about them, they cannot become adults. But modern cities are so dangerous that children cannot be allowed to explore them freely.

The need for children to have access to the world of adults is so obvious that it goes without saying. The adults transmit their ethos and their way of life to children through their actions, not through statements. Children learn by doing and by copying. If the child’s education is limited to school and home, and all the vast undertakings of a modern city are mysterious and inaccessible, it is impossible for the child to find out what it really means to be an adult and impossible, certainly, for him to copy it by doing.

This separation between the child’s world and the adult world is unknown among animals and unknown in traditional societies. In simple villages, children spend their days side by side with farmers in the fields, side by side with people who are building houses, side by side, in fact, with all the daily actions of the men and women round about them: making pottery, counting money, curing the sick, praying to God, grinding corn, arguing about the future of the village.

But in the city, life is so enormous and so dangerous, that children can’t be left alone to roam around. There is constant danger from fast-moving cars and trucks, and dangerous machinery. There is a small but ominous danger of kidnap, or rape, or assault. And, for the smallest children, there is the simple danger of getting lost. A small child just doesn’t know enough to find his way around a city.

The problem seems nearly insoluble. But we believe it can be at least partly solved by enlarging those parts of cities where small children can be left to roam, alone, and by trying to make sure that these protected children’s belts are so widespread and so-far reaching that they touch the full variety of adult activities and ways of life.

For me, Darren’s work is about restoring the balance of incorporating young people into a community, to break them away from the segregation we enforce onto them through class-rooms and age-based learning. Writing in the 1970s, Alexander hinted that unless children interact with adults, they cannot become ‘adults’ themselves. As a child of the same decade, I recognize the effects the subsequent decades have had on my generation and those that have followed. As Lorna Mills points out in one of her comments:

…brings to mind the late Neil Postman and his wonderful book The Disappearance of Childhood where he, at one point, proposed it was actually adulthood that was disappearing.

For generations we have effectively controlled the community that our children and young adults experience so that they only really know a community of each other. In my case, it was only toward my mid-twenties that I began to make friends with people significantly older than myself.

Now, that’s what I like about the Mammalian projects; that it’s a fuck-you to a society that segregates children and treats them like precious little angels and not human beings. Having watched the 1970’s The Bad News Bears recently, I was struck by how adult those adolescents seemed: they drank, smoked, swore and said offensive things. That’s pretty much how I remember that age range for myself. And yet, in the thirty years since that movie, children are now routinely depicted as being smart-alecky technical whiz-kids, cute and precious and silly, and if Speilberg’s involved, crying for their fucking daddies.

An anti-adult Boomer ideology has infected everything and I know thirty-somethings who proclaim with pride a Peter Pan syndrome (and I’m not talking about Michael Jackson). This is to say that the only valid model of Being now acceptable is the youthful one, which by definition is immature. This indoctrination leads to the belief that it is better to be pre-formed that fully-formed, better to cut yourself off from your full potential as a being, and be happy with the state leading up to it. In art terms, it is better to be a sketch than to be fully rendered.

Yes, I understand the prejudice: that adults are humourless squares. That their spirits are dead and they’ve lost their collective imagination. But I grew up with an understanding that each decade of life offered something unique to experience, and I wasn’t going to settle for the awkwardness and patronization I’d experienced throughout my childhood and adolescence as being all I could expect from life. While adults of previous generations had given the condition a bad name, that doesn’t mean we should refuse to embrace our biological destiny. A little bit of historical awareness should mean we can chose to be a type of adult that suits us. I understand today that there are those who are choosing to be Peter Pan types – fine. I just wish it wasn’t so popular.

ART

As an anonymous commenter pointed out on the Moser post, the projects ‘should be critiqued from a performance art point of view first and foremost, just as a painting would be critiqued. I’d like to see if anyone will actually look beyond the “kids in parkdale” thing and see the thing as art, because the fact that no one has so far (as far as I know) says more about our perceptions and ideologies than Darren’s.’

As art, Darren is working self-consciously working within the Relational Aesthetics stream of contemporary practice. Relational Aesthetics emphasizes events over objects – one goes to the gallery/space to experience something rather than to just see/hear something. Relational Aesthetics as a movement has already jumped the shark according to some, but I think that type of judgment just highlights an allegiance to being trendy. It is valid exploration within our structured society, which often highlights what we take for granted about our relations with one another. For example, Mammalian’s projects highlight that we take ignoring kids and their imagination for granted.

Chuck Close is said to teach his students that ‘if it looks like art, chances are it’s somebody elses’. That is, it’s familiar, established, and probably by consequence unoriginal. Art has become a series of familiar forms, and all it took was Nicolas Bourriaud to write a 114 page book and call it ‘relational aesthetics’ for artsters to stop saying ‘what the fuck’ and be all uncomfortable with the unfamiliarity, and to start exploiting the possibilities of this form of performance and theatre.

In a comment on her post, Moser uses Diana Borsato’s use of tangoing police officers (during 2006’s Nuit Blanche) as something more obviously ‘art’ because she used adults. (Borsato herself weighs in here). MDR’s use of children puts their work (for the 2006 Nuit Blanche, ‘ballroom dancing’) in the realm of ‘community art’. This seems entirely a personal interpretation on her part, but one informed by the familiar and by our privileging childhood as something ‘special’, the same way the drooling kids in our schools were ‘special’ … i.e. not ‘normal’.

That’s not denigrate ‘specialness’ and emphasize ‘normality’. The value of living in a democratic society is the expansion of possibility. When we narrow options and narrow culture to something familiar then we’ve narrowed the possibility of our imaginations. Artists know this intuitively and it’s part of the artistic ideology. The language used often contrasts boring vs. exciting, narrow vs. unlimited, possible vs. impossible, etc. It’s why there are protests against turning studios into condos, and freak-outs seeing gym-thugs in former gallery spaces turned into magazine-layout restaurants. Because a narrow frame of possibility has been drawn around something that was once more vague and voluntarily undefined.

We are still at a point socially where we don’t know how to recognize what ‘drooling kids’ have to offer, and prefer to shape people into suits, give them Blackberries and expect them to buy a house or a condo. If they jump through the required hoops to adopt ‘the form’ then it doesn’t matter if their lives are empty of meaning. All that’s important is that they look like they have something to offer (even if what they end up offering is 40+ hours of their lives a week to make their bosses’ lives easier).

(Moser points out that Canadians don’t like to talk about class, but it’s a North American and Commonwealth phenomenon – an aspect of colonial legacy. Class is part of the human psyche, and it’s an achievement of post-colonial civilization to down-play it, and a failure to see it become resurgent. Just as taught hygiene keeps certain diseases away, it’s representative of educational failure when a type of psychological typhoid manifests itself again.)

Thus, good art should bring us unfamiliar experiences. (Although, I have to say here, I’m pissed off when artists seem to chose to bring us negative unfamiliar experiences, emphasizing the disgusting and annoying as if that is somehow worth experiencing). Good art should help make us aware of the variety of possibility.

But the definition of Art itself has become too narrow to fully incorporate the explosion of creativity that we have been made aware of through the internet. Consider that in less than two years, an entirely new dialect has been created through the captioning of funny cat pictures. Oh Hai! This wasn’t controlled or planned, but just happened … through humour and through our innate sense of how (our) language works. In as much as I’m an old fashioned humanist, I am so because human beings remain consistently surprising and creative. And the arts have remained valuable and evolved away from Van Gogh landscapes into rice-cooking because in the past century, specialization and over-rationalization have become ideological, to the point that structure is confused with form and appreciated over content. We are a civilization in love with the shape of bowls, but care little about what fills them. Thus, we have edible items without nutritional content, bodies trained to exert forces unrequired for playing video games, and photographs in closets mocking the way we looked twenty years ago. And, an artist once known for filling bowls now gets away with closing doors with walls, a form contrived to evoke content forty-years out of date.

Art schools are schizophrenically complicit in this: while they teach future artists to be critical of the shapes of society, they also expect artists to fit into these shapes, to make familiar art while attempting to make unfamiliar art as well.

Perhaps it is no wonder that so much contemporary art is as bad as it is. When I was recently graduated, I used to tell myself and others that it was impossible to suck, since the anarchism on display in galleries was impossible to judge. But we still want to judge it, we want to be able to say ‘good’ or ‘bad’, and that means we each need some personal standard. What I’ve learned in the years since graduating is that artists do indeed have personal standards, and for the most part, the cliques within the art communities come together around a shared standard … but this is unpredictable, and often dependent on who one’s teacher was at whatever particular school one went to.

This insight has discredited cultural criticism for me. It is an incompatible position to want cultural anarchy as an allowance of possibility and an expansion of potential inspiration, and at the same time to want culture narrowed to the familiar and the immediately comprehensible. Personally, I haven’t quite got that down yet, and still get pissed off in galleries when I see easy work that looks like it’s wasting my time.

But I understand this duality exists in my mind because I’m a person born into the late 20th Century and seeking an expanded open future in the 21st. I am trying to unlearn 20th Century culture and learn the 21st Century one. Which is to say, I’m trying to reject the shit of the past in order to be a type of person which I feel would fit the 21st Century world that I want to live in. The 20th Century narrowed possibilities to binary check-boxes: apocalypse or utopia; 1 vs. 0, employed vs. unemployed, male vs. female, businessman or hippy, movie vs. theatre … etc. A little bit of history shows that people didn’t always live that way.

So, all this being said, I’ll sum it up this way: the Mammalian Diving Reflex projects are awesome, they’re fun, and they’re Darren’s admitted attempts to change his world by expanding his own horizons. Some people don’t get it and they’re allowed to. Some people don’t get it because they’re trying to fit a round peg into the art-world’s square hole. I get it in an idiosyncratic way that I hope I’ve shared, and in so doing hope that I’ve helped illuminate something for others. – Timothy

Believing in Creationism conveys a reproductive advantage in attracting other Creationists.

Thus, by not breeding with those who believe in Evolution, Creationists are proving the theorem of those they oppose.

ILLUMINATIONS Art in the Age of Terror

What does it mean to be an artist in the age of terror?

In our own age, as the theatre of war intrudes into our living rooms, as war increasingly becomes a spectacular media event, has the role of art vis à vis war undergone a radical change? Neil Murray, Executive Producer of the National Theatre of Scotland and Laurie Anderson, creator of the “concert-poem” Homeland (next page) are among the panelists in this discussion. Also participating are philosopher and essayist Mark Kingwell, and Jeffrey Dvorkin, professor of journalistic ethics at Georgetown University. Moderated by John Ralston Saul.

With support from: British Council

from: Timothy Comeau

to: Peggy Nash

cc: Jim Prentice, Prime Minister of Canada, Stephene Dion, Jack Layton

date: Thu, Jun 12, 2008 at 2:10 PM

subject: Opposition to Copyright reform

While I respect the Government’s desire to update copyright

legislation to be fair to all parties within the 21st Century’s

digital environment, I do not feel that the legislation introduced

today is close to achieving that goal. Rather, it attempts to

legislate into law the 20th Century status quo, wherein the consumer

is subject to terms and conditions imposed by producers without

negotiation.

I very much object to the idea – introduced in the bill – that posting

copyrighted material online (specifically pictures) could make one a

criminal. This would have a serious effect on blogging, where it has

become normal to re-post images copied from the source. In fact, it is

often used as a mean to link to the original source. And blogging is

one of the examples of the transformative effect the net has had on

our culture … a vibrant arena for debate, discussion, and the

dissemination of new knowledge. To make any part of its culture

illegal would be equivalent to introducing limits to the freedom of

expression, or – in 20th Century language – to interfere with the

freedom of the press.

This law fails to recognize net-culture as it has developed over the

past decade. There needs to be a fair-use provision which is clear,

and which allows the posting of material within legitimate contexts,

such as those that are promotional and educational.

The Toronto Star has this breakdown

“you could copy a book, newspaper or photograph that you “legally

acquired.” But you couldn’t give away the copies. And you can’t make

copies of materials you have borrowed.”

-with regards to the photographs, this would make a site such as this

(Keil Bryant’s Flickr page, which I enjoy browsing because we share an

interest in such s-f imagery) illegal, if Bryant were Canadian. It

would also become illegal (as I understand it) for me to save a copy

of any of these images for my collection.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/kielbryant/

– “- it would be illegal to post a copyright work — picture, song,

film — on the Internet without the permission of the copyright owner.”

As written above re: blogging

As a final word, the Government of Canada would be well advised to

consult with ‘share-holders’ who are representative of the base of

potential inf ringers: those under 35, who’ve grown up with VCRs and

computers. It has so far failed to do so. For those us (such as

myself) representative of this generation, a series of social norms

have developed with regard to material on the net. Trying to

criminalize downloading would be like trying to criminalize the great

Canadian tradition of saying ‘sorry’ when someone bumps into us.

Whatever legislation is introduced, technological circumvention along

with a young person’s ingenuity would counter it within 6 months (like

the jail-broken iPhone cracked by a kid in New York State two months

after its release). Under the new law, it would be illegal for future

young men ‘who hate AT&T’ do to so. We would thus be deprived of the

right to use a device with a contract we thought was fair.

We do not want to be beholden to the one-sided contracts which limit

our freedom to access digitized cultural material. In the 21st

Century, the more liberal (no pun intended) the copyright law, the

more creative the society is allowed to be. I disagree with Richard

Florida that the path to 21st Century wealth is the enforcement of

intellectual property laws, but I do agree with him that a

society/city’s wealth is a measure of its creativity … it’s a

question of how one’s define wealth. I do not define it in terms of

money, but rather in terms of inheritable, sharable, cultural

products. We thus currently enjoy a net of cultural wealth, and this

bill would seek to impoverish us all in favor of the more narrow

definition of wealth as a measure of how much a company can squeeze

from a consumer.

Timothy Comeau

timothycomeau.com

————————–

[also posted on Goodreads]

When I learned of this late last week, I thought it would have been something awesome to go to.

Until I saw the pictures.

The deets:

Monday, May 26, 6:30 PM – 8:30 PM

Munk Debates

Be it Resolved that the world is a SAFER place with a REPUBLICAN in

the White House

Discussant: Charles Krauthammer

Discussant: Niall Ferguson

Discussant: Samantha Power

Discussant: Richard Holbrooke

Co-Sponsored by The Globe and Mail, Royal Ontario Museum, Salon

Speakers Series, Aurea Foundation, Munk Centre for

International Studies

Registration: Tickets available only at: http://www.munkdebates.com

The Royal Ontario Museum

100 Queen’s Park Crescent

Toronto, Ontario

defaults write com.apple.finder AppleShowAllFiles TRUE

killall Finder

defaults write com.apple.finder AppleShowAllFiles FALSE

killall Finder

I just found this laying around the hard-drive. It’s something I wrote at the beginning of February, meant as a reply posting on a web-forum before I abandoned it as too long and potentially off-topic. I also read it now and think it dates me as a 30-something pre-Millennial with 20th Century memories. I’m not so sure the sentiments herein expressed would resonate with early 20-somethings who hate old art as being too much Church-stuff. I’m also not sure how many 20-something artists are dealing with legacy-Marxists on a regular basis, as I have over the past decade.

One of the lessons of the 20th Century was that the world changes every ten years. Each decade compressed the changes of a mediaeval century, and yet the arts don’t seem to have clued into this. My reason for pursuing the arts came from it’s humanism, as expressed especially in the 1960s, which I now recognize as being part of the Western World’s healing process following World War II. As a teenager, the Time-Life series on artists produced at that time were an introduction to a cultural world that I was not being taught in my rural Nova Scotia school.

The humanistic aspect of the arts is still what politicians and journalists are likely to throw at us – the arts encourage ‘life’ with mystical overtones. I now understand why that was propagated in the years following the Second World War, but by the time I went to art-school (following the idea that a cultured life was the one the most worth living) I ran into bitter and disagreeable adults who hated the word `beauty`, hated the word `humanism`, and instead taught me to be angry with capitalism, patriarchy, corporations and the other suspects. Thus enraged, I was then encouraged to express my thoughts on the matter through obfuscation, conceptual trickery, (and those other usual techniques) not in writing – since I was expected to be only barely literate – but my making something to be exhibited in a plain white room.

Once out of art school, I thought of myself as a young professional trained in my field and yet found that income-via-arts-employment was rare, the already-expensive credentialing inadequate, and the grant system to be more of a nepotistic lottery, and no one was as smart as they thought they were; more or less they were merely quoters, not thinkers. Old ideas, not new. As long as they could throw a quote at you from one of those bitter French men (they who hated capitalism, humanism and the usual) then they considered themselves not only smart, but superior, and it didn’t matter if their day jobs did not coincide with their training. We were all channeled into a bohemian life of obscurity and intellectual self-deception.

My sense then is that the arts professionals of Canada have totally lost track of the game. They are very quick to adopt the thinking of foreigners while denigrating their home culture. Their greatest ambition is to leave the country. Trained to be hateful of contemporary society, they are too disagreeable to be employable by the corporations who could use them. And here it comes back to the humanistic heritage – your average person who respects the arts does so because of that humanistic heritage, and yet the too-cool-for-school artist today will quickly mock this superficial understanding.

Why then, is there little art is schools? Perhaps because ’sensible’ adults don’t want their kids around the bad influence of either hippy-dippy mystics or disgruntled communists. Those of us who understand why that is an oversimplification and an unfair stereotype are the ones who probably already have their kids involved in the arts. They’re not as rare as we may think, and highlights the political thinking against universalizing art education – politicians think parents-who-want-it find a way outside of the public system. It’s a lifestyle option, and an ethnically specific one at that.

My own, disillusioned sense, is that the arts do not have the value invested into them by 19th Century European snobs. I never use the word `disinterested` for example, except when talking Kantian aesthetics. The writings of John Ruskin I find to be mostly unreadable due to being obsolete. Clement Greenberg, nor Andy Warhol, ever heard the word ‘email’ in their lifetime, let alone ‘world-wide-web’. For that matter, Warhol never got the chance to use Photoshop.

Industrial manufacturing has given us a world of aesthetically pleasing products, and talent for image making is now found in the worlds of design and illustration. (Jutxapoz magazine). Installation art tends to amount to bad set design, and performance art to bad acting. I see better art videos on YouTube than I do in galleries, and on YouTube they don’t try to be art. If you consider the Mona Lisa to be the first viral image, it’s easy to extend the consideration to how much a viral video has passed the test of the audience, making it legitimate art.

These are examples of how our world has changed, and I feel like ‘the visual arts’ are a fossilized cultural product from at most, the 1980s. Future historians will look to illustration, design, and films to gauge our culture, and especially the YouTube archives. Like the photography of a century ago, it’s the stuff taken with Kodaks that are of interest, not the stuff trying to imitate romantic paintings.

If we want to have galleries in our towns and cities, it is important that we all understand why they are important. I still value art for it’s humanism. But our culture is so creative outside of galleries, and it is this creativity that is accessible to people who haven’t studied art. The argument shouldn’t then be to have an art for those professionals – it should be accessible to all. A life in the arts should broaden one’s possibilities, not narrow them to the life of a clique.

When people talk about `art` these days, I no longer know what they’re talking about. I suspect they are talking about some hipster club they don’t want a corporate dork to join. But that exclusion denies someone who needs art is their life from having it – and the result is Canadian culture in 2008.

I sat at the table waiting for my order to be ready. It came on the radio again, the second time I’d heard it that day. An earlier radio speaker, in the morning rain.

Hearing it this second time, I flashed forward fifteen years. One day in the early 2020s, I’ll hear it buried on a radio playlist, and think back to these days. Just as I do with these songs:

Which always reminds me of the early summer of 1990. Specifically, hearing it on the car radio in the Annapolis Valley. But of course, there are also the memories of dancing to it weekend nights in 1994.

This

reminds me of gardening in the summer of 1991.

and this

brings me back to that year, half-way down the aisle under the ‘fresh’ sign in this grocery store, looking back toward the camera’s viewpoint.

But while we’re at it, let’s keep in mind that this time next year, this:

will be twenty years ago.

Warren Wagar, A Short History of the Future, page 244:

…sharp witted, yet outgoing and cooperative, the young members of Homo Sapiens altior fashioned a new model of human behavior ideally suited for life in autonomous communities. They were less inclined than the old human type to take advantage of others and too intelligent to be taken advantage of themselves. Their extraordinary powers of mind and heart were another form of wealth, shielding them, as ample personal incomes and education helped to shield everyone, from the age-old tendency of most of Homo sapiens to fall victim to predators.

As integration deepens, the generation whose identity was created by separation can feel left behind, betrayed, and lash out … at other members of the minority.

– Andrew Sullivan, parsing Wright, Sharpton, and Obama

You’ve suggested that there might be certain functions of the mind, certain aspects of consciousness, that don’t have a material foundation.

Yes.

Advanced contemplatives in the Buddhist tradition have talked about tapping into something called the “substrate consciousness.” What is that?

Just for a clarification of terms, I’ve demarcated three whole dimensions of consciousness. There’s the psyche. It’s the human mind — the functioning of memory, attention, emotions and so forth. The psyche is contingent upon the brain, the nervous system, and our various sensory faculties. It starts sometime at or following conception, certainly during gestation, and it ends at death. So the psyche has pretty clear bookends. This is what cognitive neuroscientists and psychologists study. They don’t study anything more. And they quite reasonably assume that that’s all there is to it. But as long as you study the mind only by way of brain states and behavior, you’re never going to know whether there’s any other dimension because of the limitations of your own methodologies. So here’s a hypothesis: The psyche does not emerge from the brain. Mental phenomena do not actually emerge from neuronal configurations. Nobody’s ever seen that they do.

So your hypothesis is just the reverse from what all the neuroscientists think.

Precisely. The psyche is not emerging from the brain, conditioned by the environment. The human psyche is in fact emerging from an individual continuum of consciousness that is conjoined with the brain during the development of the fetus. It can be very hampered if the brain malfunctions or becomes damaged.

But you’re saying there are also two other aspects of consciousness?

Yeah. All I’m presenting here is the Buddhist hypothesis. There’s another dimension of consciousness, which is called the substrate consciousness. This is not mystical. It’s not transcendent in the sense of being divine. The human psyche is emerging from an ongoing continuum of consciousness — the substrate consciousness — which kind of looks like a soul. But in the Buddhist view, it is more like an ongoing vacuum state of consciousness. Or here’s a good metaphor: Just as we speak of a stem cell, which is not differentiated until it comes into the liver and becomes a liver cell, or into bone marrow and becomes a bone marrow cell, the substrate consciousness is stem consciousness. And at death, the human psyche dissolves back into this continuum.

So this consciousness is not made of any stuff. It’s not matter. Is it just unattached and floating through the universe?

Well, this raises such interesting questions about the nature of matter. In the 19th century, you could think of matter as something good and chunky out there. You could count on it as having location and specific momentum and mass and all of that. Frankly, I think the backdrop of this whole conversation has to be 21st century physics, not 19th century physics. And virtually all of neuroscience and all of psychology is based on 19th century physics, which is about as up-to-date as the horse and buggy.

(source)

John Adams: Spring 1772

Government is nothing more than the combined force of society, or the united power of the multitude, for the peace, order, safety, good, and happiness of the people … There is no king or queen bee distinguished from all others, by size or figure of beauty and variety of colors, in the human hive. No man has yet produced any revelation from heaven in his favour, any divine communication to govern his fellow men. Nature throws us al into the world equal and alike … (source)

In writing this book, I have made a host of spelling “mistakes”, but have paid them no heed. Each has been signaled clearly by a red line that my computer’s U.S. text system inserts beneath the offending word. The mistakes aren’t really mine, though; they are Macdonald’s. He had an order-in-council passed directing that the government’s papers be written in the British style, as with “labour” rather than “labor”.

(p66) In 19C Canada, the observation that all politics is local would have been treated not as insight but as a banality. With occasional exception, such as the campaign to achieve Responsible Government by Population, almost all politics was about local issues. Debates that engaged the general public were almost always those inspired by sectarianism – French vs English, Catholic vs Protestant, and sometime Protestant vs Protestant, as between Anglicans and Methodists. Just about the only non-religious exception to the rule was the issue of Anti-Americanism; it was both widespread and, as was truly rare, a political conviction that promoted national unity because it was held as strongly by the French and by the English.

Almost all politics was local for the simple reason that almost everyone in Canada was a local: at least 80% of Canadians were farmers or independent fishermen. Moreover, they were self-sufficient farmers. They built their own houses. They carved out most of their implements and equipment. They grew almost all their own food (tea and sugar excepted) or raised it on the hoof. They made most of their own clothes. They made their own candles and soap. Among the few products they sold into commercial markets were grain and potash. Few sent their children to school. They were unprotected by policemen (even in the towns in Upper Canada, police forces dates only from the 1840s). For lack of ministers and priests, marriages were often performed by the people themselves. Even the term ‘local’ conveys a false impression of community: roads were so bad and farms spaced so far apart that social contact was limited principally to ‘bees’ – barn and house raising, stump clearing and later, more fancifully, quilting.

Government’s reach in Canada was markedly more stunted than in England. While there had been a Poor Law there from 1597, the first statute of the Legislature of Upper Canada provided specifically that ‘Nothing in this Act … shall introduce any of the laws of England concerning the maintenance of the poor’. (The Maritimes, then quite separate colonies, had both Poor Laws and Poor Houses). The churches were responsible for charity, and in some areas for education (The first legislation in British North America to establish free education was in Prince Edward Island in 1852. Nova Scotia followed in 1864, and Ontario only after Confederation). It was the same for that other form of social activism, the Temperance Societies, commonly brought into being by the Methodist, Presbyterian and Baptist churches. The unemployed were ‘the idle poor,’ and no government had any notion that it should be responsible for their succor. Governments collected taxes (almost exclusively customs and excise duties) and were responsible for law and order, maintaing the militia, and running the jails, where the idea of rehabilitation as opposed to punishment was unknown. But without income tax, there was comparatively little the government could do even if it wished. Consequently, the total spending on public charities, social programs and education amounted to just 9% of any government’s revenues. To most Canadians in the middle of the 19C, government was irrelevant to their day to day lives as it is today to the Mennonites, Hutterites and Amish.

[…] In mid to late 19C Canada, conservatism was as widely held a political attitude as liberalism would become a century later. It took a long while for things to change. In one post-Confederation debated, in 1876, held during an economic depression, a Liberal MP argued that the government should assist the poor. Another MP rounded on him to declare “The moment a Government is asked to take charge and feed the poor you strike a blow to their self-respect and independence that is fatal to our existence as a people.’ The shocked intervenor was also a Liberal, as was the government of the day.

Amid this emphasis on the local, there was, nevertheless, one broad national dimension. Governments were remarkably ready to go into debt – proportionally more deeply than today – to build up the nation itself. Here, Conservatives were actually greater risk-takers than the Reformers. Bishop Joseph Strachan, a leading member of the arch-conservative Family Compact, held that ‘the existence of a national debt may be perfectly consistent with the interests and prosperity of the Country’. In the early and middle part of the century, mostly Conservative governments bankrolled major public projects – first canals, such as the Welland, the Lachine and the Rideau – and then a spiderweb of railways, nearly all of them money-losing. The Conservatives were, of course, undertaking projects that benefited their supporters, but they were also building the country. [… p 69]

p. 89 A great many Canadians have come to assume that their country began on July 1 1867, not least because we celebrate each year the anniversary of Confederation. But Confederation wasn’t the starting point of all that we no have and are. It developed from its own past, and that past, even if now far distant from us, still materially affects our present and our future.

The most explicit description of the continuity of Canadian politics across the centuries is made by historian Gordon Stewart in his book The Origins of Canadian Politics. There he writes, “The key to understanding the main features of Canadian national political culture after 1867 lies in the political world of Upper and Lower Canada between 1790s and the 1860s.” His argument, one shared fully by the author, is that all Canadian politics, even those in our postmodern, high-tech, 21st Century present, have been influenced substantively by events and attitudes in the horse-and-buggy Canada of our dim past.

[…]

The catalyst of fundamental change in pre-Confederation politics were the rebellions in 1837-38 by the Patriotes in Lower Canada led by Louis-Joseph Papineau, which was a serious uprising, and by the rebels in Upper Canada led by William Lyon Mackenzie, which was more of a tragicomedy. Both uprisings provided a warning to London that, as had gone the American colonies a half-century earlier, so the colonies of British North America might also go. To deal with the crisis, the Imperial government sent out one of its best and brightest.

John George Lambton, Earl of Durham, arrived accompanied by an orchestra, several race horses, a full complement of silver and a cluster of brainy aides, one of whom had achieved celebrity status by running off with a teenage heiress and serving time briefly in jail. Still in his early forties, ‘Radical Jack’ was cerebral, cold, acerbic and arrogant. After just five months in the colony, he left in a rage after a decision of his – to exile many of the Patriotes to Bermuda without the bother of a trial – was countermanded by the Colonial Office. Back home, he completed, in 1839, a report that was perhaps the single most important public document in all Canadian history. Lord Durham himself died of TB a year later.

Parts of Durham’s report were brilliant; parts were brutal. The effects of each were identical: they both had an extraordinarily creative effect on Canada and Canadians. The brutal parts of Durham’s diagnosis are, as almost always happens, much the better known. He had found here, he declared, “two nations warring in the bosom of a single state … a struggle, not to principles, but of races (Durham’s use of the word ‘race’ will strike contemporary [readers] as odd. It was used then to describe people now usually referred to as ‘ethnic groups’.) The French Canadians, les Canadiens, had to lose – for their own sake. They were ‘a people destitute of all that could constitute a nationality … brood[ing] in sullen silence over the memory of their fallen countrymen, of their burnt villages, of their ruined property, of their extinguished ascendancy.’

In fact, Durham was almost as hard about the English in Canada. They were ‘hardly better off than the French for their means of education for their children.’ They were almost as indolent: ‘On the American side, all is activity and hustle … On the British side of the line, except for a few favoured spots, all seems waste and desolate.’ He dismissed the powerful Family Compact as ‘these wretches’. Still, he took it for granted that Anglo-Saxons would dominate the French majority in their own Lower Canada. ‘The entire wholesale and a large portion of the retail trade of the Province, with the most profitable and flourishing farms, are now in the hands of this dominant minority.’ All French Canadians could do was ‘look upon their rivals with alarm, with jealousy, and finally with hatred.’

The only way to end this perpetual clash between the ‘races’ Durham concluded, was there to be just one race in Canada. The two separate, ethnically defined provinces of Upper Canada and Lower Canada should be combined into the United Province of Canada. As immigrants poured in from the British Isles, the French would inevitably become a minority. To quicken the pace of assimilation, the use of French should cease in the new, single legislature and government. To minimize the political weight of Lower Canada 650,000 people, compared with Upper Canada’s 450,000 each former province, now reduced to a ‘section’ should have an equal number of members in the new legislature. (Officially, Upper Canada now became Canada West, and Lower Canada became Canada East. In fact, almost everyone continued to refer to the new sections by their old titles … In fact, the legislature re-legalized the use of the old Upper and Lower Canada terms in 1849).