Goodreads Intros

Mentioned amidst some of the commentary was that the House was meant to be closed six days later anyway. Checking Parliament’s website, we see that the sitting days were to continue to December 12th, before breaking for the holidays. So the heavy-handed tactic of shutting down the House rather than face a vote he knew he would lose had the effect of teaching Canadians a new word and giving the politicians some new propaganda to play with for Christmas.

Let us imagine the scenario, had things happened the way they could have.

All comment seems to agree that the Conservative party is being run as a Harper dictatorship. Party members dare not speak out against policy, for fear of the wrath of the dear leader. To say that the maligned Economic Update was ‘Harper’s economic update’ may not be inaccurate. Harper’s Economic Update was delivered on Thursday November 27th. It was to be voted on Monday December 1st. Already by Friday afternoon of the 28th, the talk of Coalition was underway, so that on the evening of that Friday, Harper said he’d push the vote back a week, ‘to give Canadians time to contact their MPs’ and to give everyone a cooling off period. Presumably, Harper was hoping that the extra time was all that was needed to diffuse the growing threat of a Coalition.

Monday December 1st 2008

Anticipated: The Fall of the Harper Government

Actual: The news conference presided over by the Liberals, NDP, and the Bloc.

The Coalition talk began to pick up steam. Conservatives had posted a website dictating talking-points to their supporters for call-in radio shows (a Macleans post on this). The week then is marked by mediocre commentary in the national press, and the dim witted web-comments by Conservative supporters who are typing ’separatists!!!’ and ‘the three stooges’, and other variations of belittlement. Up until the previous week, I used to enjoy checking out Bourque.com for a round-up of Canadian news. This past week, that site devolved into the worst of yellow journalism as it denigrated into an essentially Conservative position.

So, by Wednesday December 3rd, we’re going to be addressed by the Prime Minister. I don’t have a television and was out at the scheduled time at 7pm, so I watched it when I got home from a website. Harper came across as an abusive husband looking to be let back into the house. His see-through charm and television makeup did nothing to convince me that he’s trustworthy. Further, he blatantly tried to exploit the ignorance of the Canadian people, by implying that the Coalition did not have the right to take power, when in fact they do. The response by Dion I have not yet seen. I clicked on it and the video never launched. This was probably because it was late in being delivered. Further, I heard that it’s quality was awful, evident from the screencaps posted on accompanying stories.

All of this only to set the stage for the dramatic visit to the Governor General’s house, where she would either let Harper’s government fall, or suspend Parliament. By noon, the news had come that Parliament was being prorogued.

Monday December 8th 2008

Anticipated: The Fall of the Harper Government

Actual: Nothing

… well, as I’m writing this on Saturday the 6th, it may be too soon to tell. But Dec 8th was to be the day of the vote. So let us imagine it had gone ahead. The Harper government falls. Hipsters party on Monday night. But then what? The Coalition would take power only after Harper’s formal visit to the Governor General. He would have had to say to the Speaker that the loss of the vote demonstrates the loss of confidence in the government and he’s therefore be visiting her to ask her to dissolve Parliament and call an election. So, what happened on Thursday the 4th would have happened on the 9th. And then again, the question would have been, does the GG call for new elections, or does she allows the Coalition a chance?

The Coalition attempted to show through its documents and press conferences that it was positioned to lead the government for at least 18 months. This was in order to influence the GG into deciding to give them the chance. So, let’s imagine that she did. Somewhere around Tues December 9th or Wednesday the 10th, the breaking news is the establishment of a Coalition government. Because the hipsters had already partied on Monday, they don’t see the need to do it again.

And so … Parliament shuts down two days later, on Friday the 12th, as was scheduled. Christmastime is now all mixed up with the reality that the Conservatives are mighty pissed off to have been subject to ‘a coup’ and promise to make this special time of year toxic with their blue-branded hatred. Tidings of comfort and joy. Meanwhile, Dion is smiling everywhere and Layton is probably giving good speeches about how great things will be when they get back to Ottawa in January and deliver their throne speech.

All of this speculation is merely to say that the prorogation has probably kept the worst of this process from coming to pass before its time. But that’s not to say I wasn’t angry about it on Thursday.

I’m on record as supporting the attempts at a Coalition. I read somewhere yesterday that the prorogation allows us to test the validity of the coalition. If it falls apart by the end of January, than it was never meant to be in the first place. The events of the past week however suggest that given time, this strength of this grows rather then diffuses. I take comfort in the fact that regardless, Harper’s days as leader of the Conservative party are probably numbered.

Harper must go

My position as a citizen is this: I understand how our democracy usually works, and therefore am as prepared now as I was a month ago to live with a Minority Conservative Government. The only reason this is usually the case is because the Opposition parties always rule out working together. Even on Election night, it was clear that the NDP and the Liberals do not have enough seats by themselves to form a Coalition, and thus need the support of the Bloc.

As for the threat of the Bloc, this remains ridiculous. The Bloc do not scare me at all, I do not think of them as treasonous, and I find all call-outs to National Unity and the subsequent concept of the nation-state to be merely romantic delusion. Especially when they are promoted in web-comments by Conservative idiots quoting their dear leaders, apparently too ignorant not only to think for themselves, but to understand how our system functions.

This country is interesting because of its varied regional interests, not in spite of them. For that matter, the Bloc isn’t like other parties because Quebec isn’t like other provinces. As adults we should be able to live with that. And I think we have for the most part over the past fifteen years.

Let’s review the politics of the past decade and a half shall we? Throughout the 1990s, the Reform/Alliance party essentially was the Bloc’s Anglo equivelant, answering Western interests to the Bloc’s Eastern ones. This Western chauvinism swallowed the Progressive Conservative party ruined by the politics of Mulroney, bought new suits at Moore’s and called itself Conservative. It should be noted here that whatever genuine concerns and progressive ideas were to be found in the Reform/Alliance or the Progressive Conservatives were suddenly negated merely through the use of the Conservative label, as if to say that everyone west of Winnipeg who votes Conservative Party is incapable of believing in a progressive Canada and are born being against gay-marriage.

We should remember that this transformation was facilitated by Belinda Stronach who subsequently ran for them, was elected, but jumped ship when the pie of a Ministership was held under her nose by Paul Martin’s Liberal government. The Liberals then went on to lose an election, and Ms. Stronach found herself offering commentary at the Liberal convention in the fall of 2006. As we have seen, Canadian politics regularly delivers such WTF? moments. She subsequently quit politics, having been exposed as a power hungry go-getter who didn’t really care who was in charge as long as she had a place at the table. That’s not something I blame her for since why play the game just to be a back-bencher?

But it is to say that this game has been insidious, nepotistic, and opportunistic for a while now. Whatever Harper’s saying this week to demonize his opponents, they all understand the sport and their integrity as individuals and as a party is always subject to the hierarchy. If this country was being properly run, Dion wouldn’t be around. Someone would have had the balls by now to put him out to pasture so-to-speak, rather than let him linger on to discredit their position. Hurt feelings on Mr. Dion’s part aren’t supposed to a factor in the equation. That’s how power is exercised. The fact that Bob Rae is now stepping up to talk over Dion shows not only his ambition to lead the party, but also his qualification. Ignatieff’s fence-sitting is casting doubts on his measure as Prime Minister material.

The reason the Conservatives are currently dominant despite the weakness of their official numbers is because they don’t give a fuck about anyone’s feelings, and one can hope that this works out to our collective advantage when they draw the knives for Harper’s back. If not, as Adam Radwanski pointed out, we’re in even bigger trouble than we thought, writing: “If Conservatives are not at least seriously discussing the replacement of Stephen Harper before Parliament returns on Jan 26, he truly has succeeded in creating a cult of personality’. The last thing we need is a Maurice Duplessis holding this country back from the wonder of the 21st Century, as that dictator of Quebec did in the 1950s. However once he died the resulting Quiet Revolution rushed the province from the 19th into the 20th Century within a decade, and tried to follow-through by upgrading itself into a nation-state.

If Harper manages to enforce a nightmare of feel-good 20C Reagan-Thatcher bullshit on us while the US resurrects itself from its social catastrophe, and Europe continues to set an example for what a mostly enlightened society could be, the end result will probably be a dramatic national révolution tranquille in twenty years, by which time the rest of the world will be used to thinking of us as just another one of those third world countries of squandered potential ruled by an idiot. The talent of this country will continue to apply for US-work visas to escape the ignorance of this place. Eventually, Canada could come to resemble the southern United States, too ignorant and stupid to understand the hell we exemplify to others.

In the past I’ve said in conversations that I respected Harper as someone who didn’t seem all that bad. Sure, he’s always come across as a bit of dick, but that was personal rather than professional. After the borderline buffoonery of Chretien and the stammering incompetence of Paul Martin, he brought dignity back to the office on his election in 2006. He seemed genuinely humble and honored by the position. He had respect for the office and it was through that respect that he dignified it. Now, it could be said, the power has gone to his head, and he’s lost perspective. He now feels entitled to be Prime Minister, and fuck all of us who don’t see things his way. I’ll be no longer saying in conversations that he’s not all that bad. To that point, I want to state that I don’t regret defending him against the hyperbole of hipsters, and may continue to downplay their predictably alarmist rhetoric. This country is run best through sobriety, John A’s example notwithstanding.

Harper thoroughly failed at being a Prime Minister this past week. Yes, he failed politically by provoking the opposition parties to rebel. But even more importantly, he failed by exploiting the ignorance of the citizens. This is simply unforgivable. Harper is on record as saying that Canadians know nothing of their country, which isn’t something I’m that inclined to disagree with. The fact that he’s used this to suggest that the Coalition lacked validity, to play up the idea that his government ‘won’ the October election makes him despicable. It’s not scandalous to say that the Canadian population is largely ignorant of their history and of how their democracy functions. It is scandalous that the Prime Minister would seek to use that to his advantage rather than attempt to correct it.

The zeitgeist makes it impossible not to compare his performance with that President-Elect Obama. In February, his speech on race was described as a ‘teaching moment’, a description that rose from his approach to the situation, and from Obama’s background as a law professor. He saw an opportunity to educate and he seized it.

Harper’s opportunity to educate the population was squandered. It’s probably fair to say that he doesn’t care. The talking-points prepared for the minions to call into radio-stations proves that the Conservatives have a vested interest in keeping us mostly stupid. Yet, I don’t feel particularly alone in the country in my awareness that Harper’s a failure, and the talking points website referenced has mostly been presented with a humour suggesting some people can see it for what it is. (I don’t listen to talk radio anyway, so the propaganda effort is wasted on the like of me). The propagation of ignorance includes:

• This is what bothers me the most. The Conservatives won the election. The Opposition keeps saying that the Conservatives have to respect the will of the voters that this is a minority and so on.

…how about Liberals, NDP and Bloc respecting the will of the voters when they said “YOU LOSE”.

• And what’s this going to do to the economy. I’m sorry, I don’t care how desperate the Liberals are – giving socialists (Jack Layton) and separatists (Gilles Duceppe) a veto over every decision in government – that is a recipe for total economic disaster.

• No – do you know what set this off. When Flaherty said he was going to take taxpayer-funded subsidies away from the opposition. Now there is a reason to try and overturn an election– because the Conservatives the audacity to say “Hey, it’s a recession, maybe you should take your nose out of the trough.”

• I don’t want another election. But what I want even less is a surprise backroom Prime Minister whom I never even had the opportunity to vote for or against. What an insult to democracy

The true insult to our democracy is that such a website even exists.

On November 27th, Jim Flaherty (who should be balancing the books of a corner store in Whitby as far as I’m concerned, not the books of the Federal government) stood up to deliver an ‘economic update’. The Opposition parties were looking for an economic stimulus plan. Instead we were warned that he was removing funding from all parties, and in the weeks leading up to this, there were rumours he was considering selling-off Federal government assets in order to raise short-term cash. Again, Obama gives us some insight on what an economic stimulus package might look like. He’s calling for infrastructure investment and retrofitting of government buildings and schools. Things that would actually provide jobs. Our Minority Government is considering selling the CN Tower and wanting to fuck over their opponents.

There is no question why Harper has lost the confidence of the house. The question remains as to who our Prime Minister will be in February. – Timothy

[from Goodreads 08w49:2]

I drafted the majority of this a couple of weeks ago, in light of the recent announcement of the funding cuts. In the interim weeks, Leah Sandals and Jennifer McMackon have done better jobs than I could have in assembling related links. Also, in the past week, it became increasingly clear that Harper will call an election within the next two weeks, making these controversial cuts and copyright bill null and void unless the Conservatives return to power with another minority or, god help us, a majority.

I live in a riding with an NDP candidate, and I will with good conscious vote to reelect her. Doubly, as a citizen of Toronto, I’m in an essentially Liberal area. For this reason, it has been said over the previous two and half years (since the last election) that the Conservatives have been screwing us over. It has also been said that Harper ideally wants to destroy the Liberal party. Do we really want to have such a petty and vindictive bunch of assholes deciding things for the other 33 million of us? Equally troubling is the fact that Harper grew up in Etobicoke, which is to say, Harper hates his home town. Well, fuck him too, and the scare-mongering flyers I’ve been receiving in my mailbox.

To Take Care of Oneself

As artists, it’s not a question that society owes us a living; to use that phrase is itself problematic – to say use the word owe, suggesting a debt or some other economic transaction.

For me, I go back to my early 20s, having gone through art school and having met and befriended people who in many ways weren’t really capable of taking care of themselves. They were deficient in life skills primarily, but also in terms of coping mechanisms. It wasn’t so much that they were losers or retarded in the legitimate sense of the word, but they were just different, round pegs for society’s square holes. Myself, I’d like to live in a society of difference/variety/heterogeneity. How we deal with the challenges presented by ‘un-normal’ people is one by which we can measure the state of our civilization. Since for me civilization is about the education we provide and acquire to remove ourselves as far as possible from the states of animals (who are fearful, ignorant and cruel), a civilized society is one reflective of communities of care and of elevated compassion: a state present even in animals but which we can nurture and encourage more of as self-aware beings.

In grade school, we had a class of ‘special kids’ who were the ones in wheelchairs, or were borderline blind, or whatever. One girl in particular I remember as probably having cerebral palsy. Because of the area (rural Nova Scotia) this class might have been doubling as a day care (I’m not sure what type of education was being provided) but for the most part, adapting to the needs of these children was taken for granted as the proper thing to do. It taught me that I lived in a civilized society because these people were both cared for and not to be mocked. Through this a sense of compassion was both taught and encouraged.

In my 20s, I learned that some people weren’t able to take care of themselves. And the lesson for me was just because this is so doesn’t mean people should be poor, unemployable and underemployed, nor end up homeless. It should be possible to accept these people and make sure they have homes, enough money for food and clothing and comfortable lives. There’s no need for them to suffer just because they’re different.

Like the disabled children of my community, they should to be taken care of. As a rich society not overwhelmed by the incompetent (I’d guess they’re less than 20% of the population), it should cost peanuts to make sure these people have ok lives. Considering that the real fuck-ups who end of in jail are cared for by the state, investing in keeping the annoying from becoming homeless and moochy shouldn’t be that big of a deal.

Maybe all they need is some kind of compassionate service – a councilor or a social worker. In terms of homelessness explicitly, I’ve heard it said that many are people who would be fine if they had a stable address and a social worker to help them take their medications on time. This doesn’t seem a lot to ask. If we can provide services for those who are not able-bodied, we should also accept that some people are just born different, and that they are just not ‘able-minded’ by what are thought of as society’s norms. 1

There is room for critique as to what constitutes the able-minded, but that is for another discussion. Meanwhile we’ve had plenty of critique of society’s norms, and while that has brought to light these considerations, they haven’t done much to encourage people toward compassion.

People who aren’t capable of fitting-in (to the extent that they can’t take care of themselves in the usually accepted way) just need accommodation and consideration. It isn’t a question of being owed, but of helping people within our community. Those who are physically and congenitally disadvantaged do not argue about being owed a living, but I think they rightfully feel entitled to being treated with respect and dignity.

So, send in the artists, with century old arguments about being owed a living and expecting support from government-funded organizations. What these arguments amount to is artists saying they’re retards who can’t take care of themselves and are essentially hopeless at basic economic management. Given that it was in art school that I began to think about this (as stated), that may be case. However, unlike the trolls commenting on the newspaper-site boards, who are happy with the cuts, I didn’t consider my fellow art-students and graduated artists as losers, but simply different. And so, I’m not very sympathetic to a line of argument that plays into ignorant prejudice among those completely uneducated and insensitive to the arts. The continued begging at government coffers, based on the idea that artists are incapable of surviving without it, seems self-harming and essentially untrue.

On the one hand, artists like to argue that they’re vital to society for all sorts of reasons, but on the other hand, they’re arguing that they’re incapable of functioning within that society. Over here, arguments about the intelligence of art and the superiority of the artist over the corporate clerk, and over there, whining about capitalist exploitation in the Third World while their dealers take 50% of the price of their work. Here a sense of entitlement to government financing, while there, artists who want to be above regulation and censorship while continuing to cash the government cheques.

In a sense, artists have become the ill character of a sitcom who doesn’t want to get better because everyone has become kind and giving toward them. In that manner they’ve degraded themselves and have invited disdain, which by the end of the episode is played for laughs. One of the values of Conservatives is personal responsibility, and the ability to take care of oneself. It thus follows that Conservative governments do not see much value in funding the arts because it’s representative of coddling adults who should be able to self-manage. By arguing that they’re retarded for so long, artists have willfully invited disdain.

Canada is a hard place to live

Sixty years ago, Roberston Davies’ Fortune, My Foe was first performed in Kingston. It contains a line I’ve seen much quoted in arguments reflecting on the development of arts funding in Canada.

Everybody says Canada is a hard country to govern, but nobody mentions that for some people it is also a hard country to live in. Still, if we all run away it will never be any better. So let the geniuses of easy virtue go southward; I know what they feel too well to blame them. But for some of us there is no choice; let Canada do what she will with us, we must stay.

Davies of course did not leave, but stayed and became part of the Canadian cultural legacy. (The internationalism of the film/television and music industries meant that we can still lay claim to those stars who now live elsewhere but who began with Canadian passports). In the years leading up to the 1967 Centenary, Canadians (reflecting a post-war, mid-20th Century modernist mindset as much as anything else) invested in developing a sense of nationalism. The result of this investment is people like John Ralston Saul and Adrienne Clarkson, the only two Canadians left in the media-scape praising Canada as a nation, both old enough to have been young adults at the Centenary, and both now at an age when they just seem like old fuddy-duddies.

The children of their generation is that of my own, kids born in the ’60s and ’70s and in terms of inherited legacies, pot smoking was far more successfully passed on then the spirit of Canadian nationalism. Planted in post-war soil Canadian Nationalism flowered for 1967, was worn in the lapel of Trudeau, then withered and died as is natural for flowers and all other living things. While ambitious and certainly worth the attempt, a government funded attempt at generating an artificial trans-continental consciousness in a place so geographically varied and multicultural is retrospectively absurd and perhaps deserving of it’s demise.

But the 1950s research into this attempt was that of the Massey Commission and the result was the Canada Council. We are told legends by elders of generous funding and ‘National Gallery Biennials’, where every couple of years the National Gallery would ‘define where Canadian art was at’. (src). This was part of the Nationalistic enculturation which produced the likes of Saul and Clarkson. By this early 21st Century, the children of those boomers are much more interested in city-state politics and thinking, founding the likes of Spacing magazine, not really giving a shit about McCleans while mocking Richard Florida even as he legitimizes them to the current crop of out-of-touch establishment.

In his 1993 introduction to a reprint of Fortune my Foe, Davies describes the genesis of the play; after World War II put a stop to touring plays by independent and occasionally American theatre companies, his university friend Arthur Sutherland established a theatre company in Kingston and invited Davies to write a ‘Canadian’ play to complement the repertoire of English and American comedies. In describing this background, Davies defines an artist as ‘a person who enlarges and illuminates the lives of others.’ In commissioning a young Roberston Davies, Sutherland, although aware of the risk…

“…wanted a play about Canada. It was risky because Canada has for a long time been thought a dull country, with dull people. But there was a time when Norway was thought dull, and Ireland was thought absurd, yet both of them brought forth plays which have been acclaimed as treasures by theatres around the world.”

Which reminds me of Norman Mailer’s claim that the economic recovery of Ireland in recent years can be traced to James Joyce. In other words, the capacity of a country to see itself reflected in a work of imagination can both be an ‘enlarging’ experience and also so inspiring to bind a community together. Davies is also claiming that the difference between being considered dull and ‘interesting’ (or cool, in the present sense) is in the nature of one’s self-imagining, and the messages that puts out. If painters of the United States had confined themselves to images of the American Gothic and considered that an accurate self-representation rather than satire, would we not think of the U.S. as dull?

After offering a synopsis of his play, Davies in the ’93 introduction goes on to say that his task was to make the play not too didactic. Within the structure of the play Davies had a character of a puppeteer, a European immigrant, who is sponsored to give a puppet show by the producer characters of Philpott and Tapscott. As Davies explains, the European puppet master was reflective of the recent wave of European immigrants and refugees from devastated Europe, who brought with them Old World sensibilities about art and culture, and were met with a homegrown New World audience who did not share those same ideas.

“Message,” Davies wrote, “was very much on the lips of Canadians like Philpott and Tapscott, the do-gooders who took up the puppet-show, without having any understanding of its special quality or its cultural background, but who were convinced that the task of art was to teach – to offer a Message, in fact, and to offer it in terms that the stupidest listener could understand. Canada was, and still is, full of such people. They think of art of all kinds as a sort of handmaid to education; it must have a Message and it must get across. The truth is that art does not teach; it makes you feel, and any teaching that may arise from the feeling is an extra, and must not be stressed too much. In the modern world, and in Canada as much as anywhere, we are obsessed with the notion that to think is the highest achievement of mankind, but we neglect the fact that thought untouched by feeling is thin, delusive, treacherous stuff”.

Is it not the idea that the Conservatives, in government and individually, are people not touched by feeling? Is this not reflected in Jose Verner’s comments that she would like cultural funding to be efficient? Myself, I like efficiency since it’s about doing as much as possible with the least effort – in other words, ‘being lazy is good’ as they say in computer programing, for just this reason.

It is in fact sensible for the government to want to do this. But it is also the case that the government appears to show a disdain for the arts that lie partially in a complacency engendered by funding. Canadian art is rather pathetic and remains so because the infrastructure was set up within a moment of forethought and generosity, and instead of igniting both the imagination and the culture of the country, merely created institutions staffed by people who take the funding for granted and feel entitled within their institutional titles. Instead of fostering culture, they see themselves as beyond petty and quaint nationalistic concerns and instead fly off to Venice every couple of years to hob-nob with the planet’s remaining arrogant aristocrats, shaking away the dirt of the stupid ‘unwashed masses’ of this country who usually live in the neighborhoods the galleries move to. Admittedly, that’s being overly cynical and ignoring the good that many artist-run centres and other galleries do within their neighborhoods (before raising the market-value of neighboring properties by their presence) but such ‘good’ is questionable as a repetition of a colonial mindset that sees certain groups as needing help: bring them civilization and culture; capital-c Culture having replaced Jesus in a secular society.

On July 17th I had no idea that the programs in question even existed, and I’m in the culture business. Which is to say that the gang of young adults who have turned Toronto’s gallery-area Queen West West into another nightclub district probably have never heard of the programs either. Why then should I or they have cared on August 17th? When I didn’t know they existed I didn’t care, and now that I know they exist and may not for much longer I still don’t care that much. In effect, the Conservatives have potentially legislated my mid-July mindset into existence.

In as much as I’ve gotten emails repeating the contents of a new Facebook group, I have a suspicion this may be a lost cause. As evinced by their artist-statements, artists in this country are rarely capable of being eloquent enough to convince Conservatives or the rest of the population of their value. The Conservatives have upset an easily ignored minority, and inspired such comments as:

“when the government stops spending money on endeavours that provide next to no value to the Canadian people it is not pandering, it is good government. Am I the only person in the god forsaken country that remembers we have a fricking health care crisis? Sure, there is an element of pandering, and there is plenty of other funding that should be pulled but will not be, but the simple act of pulling funding from people who never should have received it is a good thing. End of story.” (from)

and

“I think that is what I was getting at. I’m all for supporting the arts but I feel that people of Mr. Lewis’s status and influence should not be receiving money from the government whether he is right or left wing. A friend of mine is an artist and she maintains most of the arts grants go to people who don’t need them. The real starving artists don’t have the influence to affect awards.” (from)

and

“The government is the one entity in the country that is least likely to make an intelligent decision on how to spend money. In fact, the only reasons to access government funding over private are laziness, a desire to be unaccountable for the funds you receive, and the knowledge that the general public sees no value in your product.

The government should contribute to the arts through tax credits alone. This can amount to a large amount of support, ensures there will be a respectable amount of accountability built into the system, and will bring the arts community closer to the community it supposedly serves.” (from)

yet, there is one considered argument:

“Fund the Olympics and not artists? Artists leave something behind for future generations; athletes… well, they’re fun to watch. Someone said independent producers such as Avi Lewis should pay to find their own distributors. Maybe. But then you should be consistent and argue against ALL government economic subsidies and incentives. Let’s stop subsidizing automakers, oil companies, the aerospace industry, etc. For the most part, the organizations and individuals affected here are either completely non-ideological (such as Tafelmusik) or engaging in economic development for Canadian businesses, which employ Canadians (such as the Hot Docs festival’s Toronto Documentary Forum, which among other things, brings foreign investment into Canadian productions). Finally, what’s lost here is that arts and culture have always been an important part of international diplomacy. The Tories are letting their ideology trump the national interest. Shame on them.” (from)

But in regards to Tafelmusik, a baroque orchestra playing on period instruments, they charge between $89 to $15 dollars a ticket. Surely they work a profit margin in there somewhere? Surely those wealthy egotists so eager to have their name immortalized for the a decades on a hospital wing (or listed in platinum lettering in the lobby of retarded new ‘expansions’ ignored by people waiting in line to pay $22 to see largely empty galleries) can find a mil or two to send the Bach to China?

[Cross-posted from Goodreads 08w35:2]

(From Goodreads 08w26:1)

I saw Darren O’Donnell at the Toronto Free Gallery opening last Thursday night and he told me he’d been engaged in the past week with an online debate about the validity of his work with Mammalian Diving Reflex, a debate initiated by Gabriel Moser and picked up on the Sally McKay’/Lorna Mills blog.

I’ve recently moved and had been in no rush to get the net at home set up, a situation further compounded by Rogers’ incompetence (I’m posting this from work dear reader), so this debate had escaped my attention. However, alerted by Darren, I looked up the links at work on Friday and printed off the conversation for some weekend reading. My immediate reaction (especially having converted it to page-length) was ‘wow’ – to the two documents both approximately 20 pages in length. As much as Darren was enervated by the criticism, at least this was a conversation being had.

I met Darren shortly before he began his `social acupuncture` projects, and so I’ve always felt I had an insider’s perspective on them, having participated in and been witness to some of their earlier manifestations. Further, I was at the book launch for his Social Acupuncture (meaning I read it as soon as was possible) and so I have the insight provided by his brilliant essay at the back of my mind with regard to the work.

What Moser and Sandals provide me with is the perspective of someone who doesn’t know Darren personally. Sandals is upfront in admitting she doesn’t like Darren which biases her against the work (src). Another friend of mine admitted that he didn’t quite understand what the work was about art-wise either, but at the time I countered that it was part of our culture’s move away from fiction toward non-fiction (a personal interpretation I worked out somewhat in Goodreads 07w11:1).

I do take issue with one of Moser’s interpretations, since it made me sputter in indignation. I’ve never met Ms. Moser and would like to think we could get along in the future, but I have to nominate one of her paragraphs as one of the stupidest things I’ve ever read.

Speaking of the humor of Mammalian Diving Reflex’s work with children, she wrote:

But the pessimistic part of me thinks that the humour actually lies in something far less self-aware and much more sinister. This part – let’s call it the UBC indoctrinated part – thinks that the humour actually comes from a strange and almost colonial kind of child-adult anthropomorphism. That when adults see these kids trying to play grown up, the humour comes from the fact that we think they’re ‘cute’ in a patronizing way – that their inability to successfully inhabit these [adult] roles is funny in the same way that watching a dog awkwardly dressed in a human business suit is funny.

Anthropomorphism is a completely inappropriate concept to apply to children, suggesting that they aren’t part of our species (only adults are truly human ?) but are akin to dogs dressed up. I am surprised that this thought occurred to her, and doubly surprised that she saw fit to publish it. If only UBC indoctrination had taught her to recognize foolishness when it occasionally occurs, even in the best of minds.

I find nothing humorous about the Mammalian Projects, nor does ‘cute’ really enter into it for me. I’m informed by Darren’s ideas about acupuncture – that you’re poking a dam to hopefully collapse it and return the flow – and in this case, Darren is working with our society’s totally fucked up ideas about children. These ideas are so fucked up that a writer doesn’t recognize how inappropriate it is to use the word ‘anthropomorphic’ when speaking of them.

I keep thinking of a passage from Christopher Alexander’s Pattern Language. In Pattern 57, Children in the City Alexander wrote:

If children are not able to explore the whole of the adult world round about them, they cannot become adults. But modern cities are so dangerous that children cannot be allowed to explore them freely.

The need for children to have access to the world of adults is so obvious that it goes without saying. The adults transmit their ethos and their way of life to children through their actions, not through statements. Children learn by doing and by copying. If the child’s education is limited to school and home, and all the vast undertakings of a modern city are mysterious and inaccessible, it is impossible for the child to find out what it really means to be an adult and impossible, certainly, for him to copy it by doing.

This separation between the child’s world and the adult world is unknown among animals and unknown in traditional societies. In simple villages, children spend their days side by side with farmers in the fields, side by side with people who are building houses, side by side, in fact, with all the daily actions of the men and women round about them: making pottery, counting money, curing the sick, praying to God, grinding corn, arguing about the future of the village.

But in the city, life is so enormous and so dangerous, that children can’t be left alone to roam around. There is constant danger from fast-moving cars and trucks, and dangerous machinery. There is a small but ominous danger of kidnap, or rape, or assault. And, for the smallest children, there is the simple danger of getting lost. A small child just doesn’t know enough to find his way around a city.

The problem seems nearly insoluble. But we believe it can be at least partly solved by enlarging those parts of cities where small children can be left to roam, alone, and by trying to make sure that these protected children’s belts are so widespread and so-far reaching that they touch the full variety of adult activities and ways of life.

For me, Darren’s work is about restoring the balance of incorporating young people into a community, to break them away from the segregation we enforce onto them through class-rooms and age-based learning. Writing in the 1970s, Alexander hinted that unless children interact with adults, they cannot become ‘adults’ themselves. As a child of the same decade, I recognize the effects the subsequent decades have had on my generation and those that have followed. As Lorna Mills points out in one of her comments:

…brings to mind the late Neil Postman and his wonderful book The Disappearance of Childhood where he, at one point, proposed it was actually adulthood that was disappearing.

For generations we have effectively controlled the community that our children and young adults experience so that they only really know a community of each other. In my case, it was only toward my mid-twenties that I began to make friends with people significantly older than myself.

Now, that’s what I like about the Mammalian projects; that it’s a fuck-you to a society that segregates children and treats them like precious little angels and not human beings. Having watched the 1970’s The Bad News Bears recently, I was struck by how adult those adolescents seemed: they drank, smoked, swore and said offensive things. That’s pretty much how I remember that age range for myself. And yet, in the thirty years since that movie, children are now routinely depicted as being smart-alecky technical whiz-kids, cute and precious and silly, and if Speilberg’s involved, crying for their fucking daddies.

An anti-adult Boomer ideology has infected everything and I know thirty-somethings who proclaim with pride a Peter Pan syndrome (and I’m not talking about Michael Jackson). This is to say that the only valid model of Being now acceptable is the youthful one, which by definition is immature. This indoctrination leads to the belief that it is better to be pre-formed that fully-formed, better to cut yourself off from your full potential as a being, and be happy with the state leading up to it. In art terms, it is better to be a sketch than to be fully rendered.

Yes, I understand the prejudice: that adults are humourless squares. That their spirits are dead and they’ve lost their collective imagination. But I grew up with an understanding that each decade of life offered something unique to experience, and I wasn’t going to settle for the awkwardness and patronization I’d experienced throughout my childhood and adolescence as being all I could expect from life. While adults of previous generations had given the condition a bad name, that doesn’t mean we should refuse to embrace our biological destiny. A little bit of historical awareness should mean we can chose to be a type of adult that suits us. I understand today that there are those who are choosing to be Peter Pan types – fine. I just wish it wasn’t so popular.

ART

As an anonymous commenter pointed out on the Moser post, the projects ‘should be critiqued from a performance art point of view first and foremost, just as a painting would be critiqued. I’d like to see if anyone will actually look beyond the “kids in parkdale” thing and see the thing as art, because the fact that no one has so far (as far as I know) says more about our perceptions and ideologies than Darren’s.’

As art, Darren is working self-consciously working within the Relational Aesthetics stream of contemporary practice. Relational Aesthetics emphasizes events over objects – one goes to the gallery/space to experience something rather than to just see/hear something. Relational Aesthetics as a movement has already jumped the shark according to some, but I think that type of judgment just highlights an allegiance to being trendy. It is valid exploration within our structured society, which often highlights what we take for granted about our relations with one another. For example, Mammalian’s projects highlight that we take ignoring kids and their imagination for granted.

Chuck Close is said to teach his students that ‘if it looks like art, chances are it’s somebody elses’. That is, it’s familiar, established, and probably by consequence unoriginal. Art has become a series of familiar forms, and all it took was Nicolas Bourriaud to write a 114 page book and call it ‘relational aesthetics’ for artsters to stop saying ‘what the fuck’ and be all uncomfortable with the unfamiliarity, and to start exploiting the possibilities of this form of performance and theatre.

In a comment on her post, Moser uses Diana Borsato’s use of tangoing police officers (during 2006’s Nuit Blanche) as something more obviously ‘art’ because she used adults. (Borsato herself weighs in here). MDR’s use of children puts their work (for the 2006 Nuit Blanche, ‘ballroom dancing’) in the realm of ‘community art’. This seems entirely a personal interpretation on her part, but one informed by the familiar and by our privileging childhood as something ‘special’, the same way the drooling kids in our schools were ‘special’ … i.e. not ‘normal’.

That’s not denigrate ‘specialness’ and emphasize ‘normality’. The value of living in a democratic society is the expansion of possibility. When we narrow options and narrow culture to something familiar then we’ve narrowed the possibility of our imaginations. Artists know this intuitively and it’s part of the artistic ideology. The language used often contrasts boring vs. exciting, narrow vs. unlimited, possible vs. impossible, etc. It’s why there are protests against turning studios into condos, and freak-outs seeing gym-thugs in former gallery spaces turned into magazine-layout restaurants. Because a narrow frame of possibility has been drawn around something that was once more vague and voluntarily undefined.

We are still at a point socially where we don’t know how to recognize what ‘drooling kids’ have to offer, and prefer to shape people into suits, give them Blackberries and expect them to buy a house or a condo. If they jump through the required hoops to adopt ‘the form’ then it doesn’t matter if their lives are empty of meaning. All that’s important is that they look like they have something to offer (even if what they end up offering is 40+ hours of their lives a week to make their bosses’ lives easier).

(Moser points out that Canadians don’t like to talk about class, but it’s a North American and Commonwealth phenomenon – an aspect of colonial legacy. Class is part of the human psyche, and it’s an achievement of post-colonial civilization to down-play it, and a failure to see it become resurgent. Just as taught hygiene keeps certain diseases away, it’s representative of educational failure when a type of psychological typhoid manifests itself again.)

Thus, good art should bring us unfamiliar experiences. (Although, I have to say here, I’m pissed off when artists seem to chose to bring us negative unfamiliar experiences, emphasizing the disgusting and annoying as if that is somehow worth experiencing). Good art should help make us aware of the variety of possibility.

But the definition of Art itself has become too narrow to fully incorporate the explosion of creativity that we have been made aware of through the internet. Consider that in less than two years, an entirely new dialect has been created through the captioning of funny cat pictures. Oh Hai! This wasn’t controlled or planned, but just happened … through humour and through our innate sense of how (our) language works. In as much as I’m an old fashioned humanist, I am so because human beings remain consistently surprising and creative. And the arts have remained valuable and evolved away from Van Gogh landscapes into rice-cooking because in the past century, specialization and over-rationalization have become ideological, to the point that structure is confused with form and appreciated over content. We are a civilization in love with the shape of bowls, but care little about what fills them. Thus, we have edible items without nutritional content, bodies trained to exert forces unrequired for playing video games, and photographs in closets mocking the way we looked twenty years ago. And, an artist once known for filling bowls now gets away with closing doors with walls, a form contrived to evoke content forty-years out of date.

Art schools are schizophrenically complicit in this: while they teach future artists to be critical of the shapes of society, they also expect artists to fit into these shapes, to make familiar art while attempting to make unfamiliar art as well.

Perhaps it is no wonder that so much contemporary art is as bad as it is. When I was recently graduated, I used to tell myself and others that it was impossible to suck, since the anarchism on display in galleries was impossible to judge. But we still want to judge it, we want to be able to say ‘good’ or ‘bad’, and that means we each need some personal standard. What I’ve learned in the years since graduating is that artists do indeed have personal standards, and for the most part, the cliques within the art communities come together around a shared standard … but this is unpredictable, and often dependent on who one’s teacher was at whatever particular school one went to.

This insight has discredited cultural criticism for me. It is an incompatible position to want cultural anarchy as an allowance of possibility and an expansion of potential inspiration, and at the same time to want culture narrowed to the familiar and the immediately comprehensible. Personally, I haven’t quite got that down yet, and still get pissed off in galleries when I see easy work that looks like it’s wasting my time.

But I understand this duality exists in my mind because I’m a person born into the late 20th Century and seeking an expanded open future in the 21st. I am trying to unlearn 20th Century culture and learn the 21st Century one. Which is to say, I’m trying to reject the shit of the past in order to be a type of person which I feel would fit the 21st Century world that I want to live in. The 20th Century narrowed possibilities to binary check-boxes: apocalypse or utopia; 1 vs. 0, employed vs. unemployed, male vs. female, businessman or hippy, movie vs. theatre … etc. A little bit of history shows that people didn’t always live that way.

So, all this being said, I’ll sum it up this way: the Mammalian Diving Reflex projects are awesome, they’re fun, and they’re Darren’s admitted attempts to change his world by expanding his own horizons. Some people don’t get it and they’re allowed to. Some people don’t get it because they’re trying to fit a round peg into the art-world’s square hole. I get it in an idiosyncratic way that I hope I’ve shared, and in so doing hope that I’ve helped illuminate something for others. – Timothy

[From Goodreads 08w14:4]

Honestly, if a business can’t afford to pay all its employees a livable wage, than that business should be considered a fail. What are businesses for? (The wrong answer is to say the enrichment of the owners at the expense of the employees, because that’s like Marxism or something, and we’re supposed to be past all that).

I remember when I was working for a minimum wage in Halifax, feeling both totally exploited and humiliated into enforced poverty. Further, the business had like 6 people on the payroll when it only really needed three. That’s where I got the idea that mismanagement should never be an excuse to pay people peanuts. And why I have no sympathy for the business owners who claim raising the minimum wage would be too hard on them. They’re not paying themselves a minimum wage are they?

My greater concern for raising the minimum wage is this society’s capacity to maintain an unfair status quo. As is pointed out in this article, adjusted for inflation, today’s Ontario minimum wage is equivalent to what it was thirteen years ago. I’ve noticed in the past that whenever the minimum wage goes up, so do the prices at Tim Hortons, (which I consider to be an unofficial index of inflation). So the gains of the working poor are immediately offset to erase them. The article begins by pointing out that the Ontario minimum wage went up last week. This week Tim Hortons had signs at its counters saying the prices of some menu items would rise next week. Two weeks ago, the Go Train commuter system rose its ticket prices too.

So, in 2010, when the minimum wage rises to $10 and hour, count on 1.60 coffees (rather than the current 1.42 lg) at your national coffee chain, and corresponding ticket prices across our belle province and sun-shiny country. – Timothy

08w08:1 Review & Preview: The Canadian Art Reel Artists Film Festival 21-24 Feb 2008

[Cross posted from Goodreads 08w08:1]

The Canadian Art Reel Artists Film Festival, 21-24 February 2008

http://www.canadianart.ca/foundation/programs/reelartists/2008/01/24/

http://www.canadianart.ca/microsites/REELARTISTS//schedule/

screening at the Al Green Theatre, Miles Nadal JCC

750 Spadina Ave (at Bloor), Toronto

In his as-yet-untranslated book Formes de Vie (1999) Nicolas Bourriaud makes the argument that Duchamp treated the gallery as a film camera, a box in which the gallery ‘recorded’ the work and in so doing made it art. Throughout the 20th Century, the dominance of film as a medium has seeped into our consciousness to such an extant that it seems that all art today works in cinematic terms. The spectacle, the grandeur, the big budgets … the gallery has become a film set and must borrow from the film-production’s capacity to make the impossible real. Take for example the open pits of crude oil shown in There Will Be Blood – accurately reflecting the lack of environmental concern of a century ago, and yet filmed in 2006 under conditions that were probably heavily controlled and legislated behind the scenes. Also consider something like Doris Salcedo’s Shibboleth, where the Tate gallery undertook intentional damage to the foundations of the building and displayed it with an aloofness which makes it seem no big deal.

But the ugliness of its construction is as hidden as that which goes into the manufacture of our consumer goods by foreign wage slaves. We are only asked to marvel at the gleam, and not think of the grime.

I raise this points as an introduction to the blending of the cinematic and locational art forms, which is annually celebrated by the Canadian Art Foundation’s film series of artist documentaries. This year’s selection have a common theme of monumentalism, and the documentaries give us insight and access to the grime behind the gleam of art-stardom. Having watched previews of most of the films in this year’s series, (I was provided with all but four of the series’ screeners) what follows are reviews and reflections on them.

Jeff Wall | Jeff Wall – Retrospective 58:42 dir. Michael Blackwood (2007)

Peter Galassi (L) and Jeff Wall (R)

This film is an hour long eavesdrop as Wall walks through his 2007 retrospective exhibition at MOMA with its co-curator Peter Galassi. The format makes it a little boring at times – but it’s worth it if you’re at all interested in his work, and Wall gives wonderful insights into what inspired his classic pieces. It can be said that he’s a painter using photography to make his images, which are so composed and choreographed to assume the one-off aspect of a painting, albeit made in a medium which ensures a maximum reproducibly. Looking at Wall’s backlit images I was reminded they are precursors of the digital photographs we are all getting used to. One imagines that many HD-flat screen panels will be used to display future photography, as luminous and well resolved as a Jeff Wall. It makes his work seem almost prescient in that regard, and makes the technology behind it seem merely primitive rather than gimmicky or even as sophisticated as it appeared ten years ago.

Philip Johnson | Philip Johnson: Diary of an Eccentric Architect 55:00 dir. Barbara Wolf (1996)

Philip Johnson and Rem Koolhaas in the rain

This film is essentially a grand tour of Johnson’s sprawling estate in New Canaan, Connecticut, which was used as a literal field of experimentation by the architect. Johnson gives tours of the projects he undertook on his land over fifty years, meanwhile the film documents the construction of one such experiment, a building inspired by Frank Stella (who comes to see the work in progress), and which when completed is visited under umbrella by Rem Koolhaas. Once painted, it looked magnificent. I appreciated the inclusion of a scene where the construction workers quarrel with the managers, who are quibbling over ten-grand. ‘Ten thousand dollars is a drop in a hat. I see your place over there, you’re not working for $25/hr with guys making $12/hr, and think you’re going to live on that’. This sentence encapsulates what’s wrong with startchitecture to begin with, and for me is the key-phrase of the film.

As we go forward, this documentary may become one of those historical curiosities in which the rich playboy gives a tour of his Versailles and the interconnected social and environmental repercussions are totally ignored. Johnson (who I’ve most often seen in a suit at the office commenting in documentaries on the work of other architects) here is seen as a full resolution person, who had lived a blessed life of success and had reached an age when he couldn’t help but take it all for granted. His personal art gallery, brilliantly designed to exhibit many large paintings in a small space, consists of work that he needs explained to him by an assistant who first appears in the film sitting in the gallery in such a way that I mistook him for a Duane Hanson. Had The Simpson’s Mr Burns been written as an architect, he would have been modeled on Philip Johnson, and this Mr Burns would return the affections of his Smithers.

Bas Jan Ader | Here is always somewhere else 70:00 dir. Rene Daalder (2006)

Bas Jan Ader died the year I was born, and yet he has the best artist website I have ever seen, the result of some benefactor buying up his estate in recent years. As a part of this media revival, Rene Daalder was asked to make this film by Ader’s widow. (The trailer can be seen on the Ader website here). This film was a little slow getting started but got more interesting near the half-way mark. One of the nice things about this feature is how Daalder revisits some of the locations Ader used for his art-films, which have been so transformed in the intervening years as to have become unrecognizable.

Featuring interviews with people inspired by Ader’s work, including Tacita Dean, we learn much about his background, and the similar background of Daalder, who attempts to tell Bas Jan’s story by giving us insight into his own. Before he too immigrated to Los Angeles, Daalder began as a film-maker in Holland (one of his early films’s stared Rem Koolhaas, thirty years before getting his rainy day tour at Philip Johnson’s) before leaving after his first ‘most-expensive Dutch film ever’ failed at the domestic box-office. The result is a story of a small group of Dutch expatriates who ended up in L.A. trying and make their fame and fortune in Hollywood. With the exception of Koolhaas, they succeeded while remaining obscure. For example, one of the actors in another early Daalder film was Carel Struycken who I was familiar with as Mr. Homn, Lexanna Troi’s butler from the Star Trek episodes I watched as a teenager, and who also starred in the Adam’s Family movie as Lurch.

Wikipedia states that Ader’s work began to be revived in the early 1990s, and I first learned about him through the Phaidon Conceptual Art book, published in 1998. Richard Rorty described genius as the coincidence of one’s personal obsession meeting a public need. Throughout the 1980s, Bas Jan Ader was to a small group of Dutch men just that friend who disappeared at sea. As one says early on in the film, ‘I didn’t know I was friends with a myth’. This myth was constructed in the early 1990s, which is to say that the public need for Ader’s obsession only began then, this public being an art-world increasingly interested in the type of work Ader produced. As a video artist, his work can be seen throughout the movie (and on his website), and on the one hand it can seem both boring and absurd (what’s up with all the falling?) but on the other it can seem interesting and profound (the sea captain who had thought about it a lot). Ader’s work is a reminder to artists that there’s an potential audience for anything, but it may take twenty years after your death for the public’s interest to coincide with your obsessions.

Richard Serra | To See is to think 44:33 dir. Maria Anna Tappeiner (2006)

In Sheila Heti’s interview with Dave Hickey, he says of Richard Serra that ‘he’s totally not hip, can’t speak without drawing’. Throughout this film Serra is seen carrying a sketchbook, and only once to we see him actually using it. I’ve often thought that Serra’s work will survive for as long as there’s no iron shortage, but give us another couple of hundred years of material squandering, and then will see if this stuff is really worth something as art. Serra’s obsession with drawing allows one to see his sculpture really as a drawing in itself – only he is marking three dimensional space with the material of steel, rather than working with graphite or charcoal on two-dimensions. This image illustrates this for me: a simple line drawing, highlighting the space of the sky, consisting of one of Serra’s steel sheets seen edge-wise. (Of course, this interpretation is aided by the framing offered by the film camera).

Serra’s work makes me question wether things like Stonehenge were really about the stars and the Equinoxes. Perhaps they too liked to mark space with massive objects? I hope that Serra’s work, if it survives future material scarcity, will never be interpreted as astrological charting. That would make our culture look unimaginative. It’s worth persevering the memory of these rusted pieces of steel as attempts to mark the landscape in a creative way, although here I’m again reminded of what bothered me about Johnson’s estate. The land was fine as it was, and along came some egotistical human set about ‘improving’ it by dumping a hunks of rusted metal in it. I don’t think we’ve (as a culture) quite figured out the balance between imagination and destruction.

Anish Kapoor | Art in Progress: Anish Kapoor 27:24 dir. John Wyver (2007)

Anish Kapoor discussing the maquette for his installation of Svayambh

This documents the Kapoor retrospective which opened three months ago (Nov 2007) in Germany. Kapoor is one of the bigger names in sculpture right now, but he’s another reminder that artists these days (when they are successful) make big work that highlights vulgar industrial excess (a block of red wax weighing 45 tons and measuring 10 x 4.5 x 3.5 meters. WTF?) and it’s all ok because there’s enough money in the world, it’s affordable to these aristocrats, and besides, what else are we going to do with 45 tons of red wax? Cover cheese with it?

Kapoor emphasizes that his work is about color. The monumentalism of its material just seems like a paradoxical cheap trick: an expensively produced contrivance. Like, this is what it takes to awe people today – not fragility, not the delicate, but the heavy metal (Serra) in your face ear-bleeding loud message. The red wax is awe-some because it’s big.

In a world where the British-American Empire is guilty of war crimes while we face environmental catastrophe, this type of work just pokes my cynicism. When the process is supposed to be an important part of the work, and when that process is fictionalized (as it appears to be in this case) than what is the work but bullshit? Asking me to imagine the process just renders such installations as the set-design for an unmade film that it so often appears to be these days. With that in mind, I’d much rather walk through the set of the now-filming Star Trek movie than look at a giant block of red wax smeared against a gallery’s wall. Then again, if I saw this is person I might disagree with what I’ve just written.

Sam Wagstaff | Black White + Grey: A Portrait of Sam Wagstaff 72:15 dir. James Crump (2007)

As Philippe Garner (Director of Photography at the London Christie’s) says near the end of this documentary, ‘It horrifies me to think that there’s a generation growing up now in photography that doesn’t know who Sam is. And yet his legacy permeates the field, there’s absolutely no doubt about that.’

Featuring an extensive appearance by Patti Smith, roommate of Maplethorpe and part of the relationship wherein Maplethorpe took advantage of his wealthy sugar-daddy Sam Wagstaff, this is also a reminiscence of the New York 1970s art-scene and gay-demi-monde. What I most appreciated learning was that Wagstaff was responsible for a vast bulk of the collection of Getty Images.

There was some structural problems with this film’s editing, near the middle it became too crowded with interviews and from that point began to seem incongruous. Nevertheless a nice history of a man who helped change the direction of art through his curation and who amassed one of the most important photo collections in the world.

Phyllis Lambert | Citizen Lambert: Joan of Architecture 52.00 dir. Teri Wehn-Damisch (2006)

One scene of this I recognized as something I’d seen on TVO’s Masterworks last year – a scene where Phyllis Lambert-neé Brofman is walking through a Mies van der Rohe building and showing disgust at the curtains put up in its lobby. If I remember correctly, that scene was originally from a Mies-centered documentary. One of the fellow-architects interviewed for this portrait of Lambert (ridiculously modeled on Citizen Kane for god-knows-what reason) stated that architecture as we know it today would not have been without Lambert, primarily because when her family wanted to build their corporate phallic symbol in New York, she reviewed the initial design and convinced them to hire Mies instead, the result being the Seagram building. This resulted in a collaboration between Mies and Phillip Johnson, reputations established and architectural history writ. Considering how devastating architecture has become (the renegade architect Christopher Alexander having declared most of it ‘insane’) Lambert’s role is either a good thing or a bad thing considering which side your on.

Rodin | Rodin: The Sculptor’s View 53:00 dir. Jake Auerbach (2006)

Interviews with contemporary sculptors on the legacy of Rodin. This is really for sculpture geeks. Featuring Antony Gormley, Marc Quinn, Rachel Whiteread, Rebecca Warren, Barry Flanagan, Tony Cragg, Anthony Carro and Richard Deacon. (I just copied that from the blurb, incase those names spark any interest on your part. Honestly, this one I found the least interesting, since I’m not a sculpture geek. It’s just sculptors talking shop, with requisite cinematic close ups of Rodin’s work).

Tickets and times for the screenings available at the links listed above.

From Goodreads 07w49:4

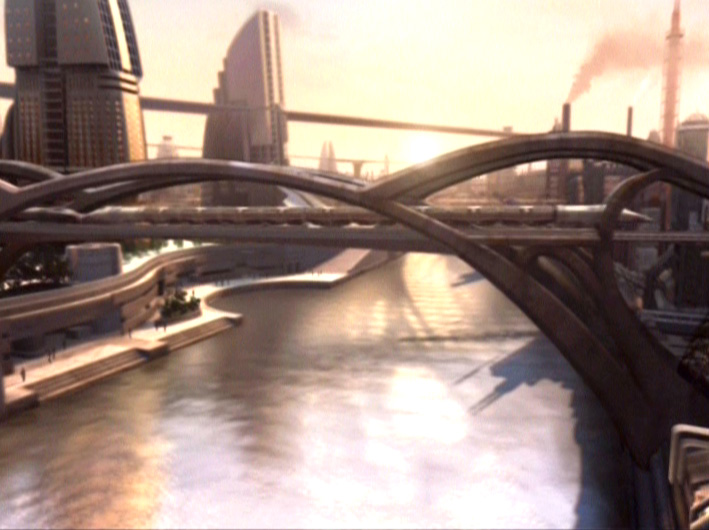

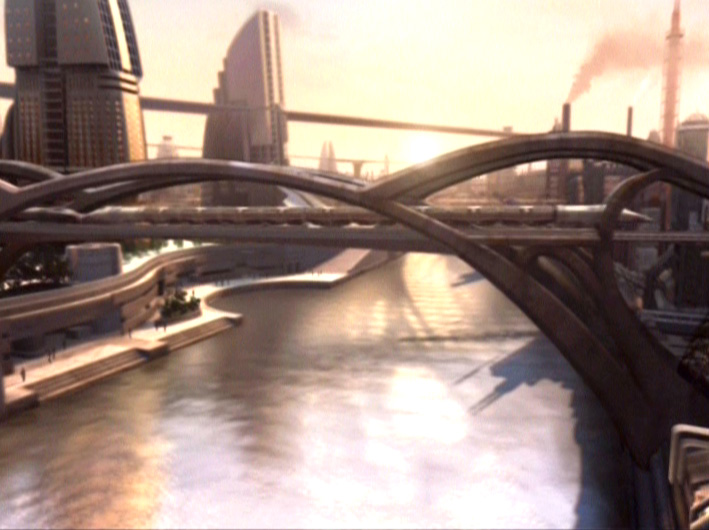

Figure 1. A 22nd Century Bridged City

The above is actually from an episode of the Star Trek series Enterprise. It came to my attention the other day through a montage depicting history in another episode of the series. As fans of the show know, one of the running plots involved time travel, and the depiction of human history ‘resetting itself’ (after plot related meddling) was done through the use of images from various sources grouped together into thematically recognizable decades. So the 1980s were depicted by images of Ronald Regan, Margaret Thatcher, and Ruhollah Khomeini, the 1990s by images of the Clintons, George H Bush shaking the hand of Mikhail Gorbachev, etc. After the depictions of the first half the present decade (scenes of 9/11, Bush & Blair) it moves on into speculation. (The images from the stream are available here). The future was represented by a car and a robot and from then onto scenes of the show’s 22nd Century, marked by the opening shot of the series, the launch of the Enterprise spaceship, in the year 2151 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cpt Archer in the Timestream

The 22nd Century is therefore marked by two cityscapes, one being that of Figure 1 the other being the following. These are meant to be Earth cities given the context of the time stream, but both shots are re-used production art from previous episodes. As I’ve mentioned, the cityscape below is from a Season 1 show (‘Dear Doctor’), while the bridge above is from an episode of Star Trek Voyager‘s last season (‘Workforce Part 1’).

Figure 3. Toronto, 2110 AD

With regard to Figure 3, because it is otherwise unlabeled and supposed to depict an Earth city in the 22nd Century, I thought it might as well be Toronto. We can imagine this stretch of waterfront as being a bit to the East, or a bit to the West, of the CN Tower thus accounting for its absence (or, I could just invite anyone to Photoshop it in). We can imagine the bridges are subway extensions to the island, and we see that a similar subway/covered LRT path runs right along the water.

This being an image originally from s-f, it reflects the current architectural trends of the beginning of the 21st Century, the postmodernist appreciation of angles, glass and concrete.

But I present this image to you thus as a reflection of what kind of city we’ll get if this century is to be one of starchitects. This is what another hundred years of Frank Gehry and Daneil Leibskinds will result in.

Does this city look like a place you’d want to live? We can spy green-space but it seems very sparse. And don’t give me the old, ‘who cares I’ll be dead’ routine, so common from the likes of the Baby Boomers. It’s precisely that type of attitude which has gotten us our present shit world, and I don’t want to encourage more of that. Given the extension of our lifespans over the past century, it’s not unreasonable to suggest that this could be the city of your elder years, so take the question seriously: is this where you want to hobble and feed pigeons? Further, are you so selfish as to be that uncaring about the type of environment our proverbial great-and-beyond-grandchildren will live in?

Figure 4. Caprica City, from the Battlestar Galactica Miniseries (2003)

A much more dramatic depiction of the type of city we could end up with it that from Battlestar Galactica. Filmed in Vancouver, perhaps one could label this ‘Vancouver 2210 AD’ since it seems a bit more harsh than the aesthetic presented above, as if one needed another century to get both the flying cars and the brutal deadness of the civic space:

Figure 5. Caprica City Detail

The real nightmare of urban development is this uniform cityscape of similar buildings, all equally unadorned, apparently utilitarian, with a neglected use of green space.

As spaces designed on computers to provide semiotic scenes meant to convey an advanced technological civilization, these reflect in turn the imagined futures of our own civilization. This is what we could end up with. But, in all likelihood, my guess is that the 22nd Century will not look like any of these images.

When Martin Rees published his book Our Final Hour in 2003, he famously gave our ‘civilization as we know it only a 50-50 chance of surviving the 21st century.’ (quote source) Now there’s some ambiguity there: others predict the potential extinction of humanity, which would certainly ruin our civilization, but it could also anticipate a sort of apocalyptic collapse into another form of Mad Max Dark Ages. But I have to point out the civilization known to the British in 1903 – and globally, that of every other nation and ethnic group on the planet (with the exception of those still living isolated tribal lifestyles) did not survive the 20th Century. The British Empire fell, the reliance on coal was replaced with that of processed crude oil, and the colonial projects of the era came to ignominious ends – the consequences of which we are still processing. Given how squanderous of natural resources our present civilization-as-we-know-it is, there’s no reason to want it to survive the 21st Century.

Which brings me to Prince Charles, who by the times spoken of here will be thought of as King Charles III. In the early 1980s, Charles was mocked by the media for his interest in organic farming, and he’s currently thought of as daft for his architectural interests, including his sponsorship of the community of Poundbury. Poundbury is the result of Charles’ interest in the work of Leon Krier and Christopher Alexander. As the Poundbury website records:

Poundbury is a mixed urban development of Town Houses, Cottages, Shops & Light Industry, designed for the Prince of Wales by Architect Leon Krier on the outskirts of the Dorset County Town of Dorchester. Prince Charles, The Duke of Cornwall, decided it was time to show how Traditional Architecture and Modern Town Planning could be used in making a thriving new community that people could live & work in close proximity. Poundbury has now become World Famous as a model of urban planning, with regular visits from Councillors and MPs. Welcome to the Poundbury Community Website!

Given how Charles has already displayed some prescience when it came to organic agriculture, anticipating both its sense and its popularity, my expectation is that he’s once again onto something with his interest in such small-scale, community oriented architecture. The end result will be cityscapes of the 22nd Century which will not reflect the imagined exaggerations of the present shown to us through easy digital mock-ups.

I return now to the city of the bridge. When I saw this in the Timestream montage, the lines of it brought to mind the position just stated: that by the 22nd Century, technological advance combined with a rejection of explicit postmodernist, angular, and Leibskind-like egotism will brings us a meld of the tradition and the technological. The bridged city seemed a place inspired by Lord of the Rings, a technological version of Rivendell.

Figure 6. Rivendell,

from The Fellowship of the Ring (2001)

Figure 7. Rivendell,

from The Fellowship of the Ring (2001)

Figure 8. A bridge in Rivendell,

from The Fellowship of the Ring (2001)

Figure 9. Rivendell,

from The Fellowship of the Ring (2001)

Given a choice between Caprica, or the Toronto of 2110 suggested here, I’d take a Rivendell of any season, of any weather condition. Of course, I expect to be able to continue to use a high speed internet connection, use a cell-phone, browse in an Apple Store, and be able to have sushi. The point here is we can take much more control over our built environment, and expect more from our architects than glass and concrete. Letting current architectural fashion guide the next several generations will only result in a Caprica like monstrosity.- Timothy

From Goodreads 07w45:3:

November in Canada is a season of two contradictory impulses. The first is the Massey Lectures, a series of five one hour lectures delivered on CBC Ideas for a work-week sometime during this month. The Massey Lectures to me represent some of the better characteristics of our species: the desire to not only grow in knowledge, but to communicate it as well. This lecture series invites the so called expert to break down the professional linguistic barriers that too often separates them from a broad audience.

The Massey Lectures used to invite scholars and writers of international habitation, but since the mid-nineties have focused on Canadian speakers, highlighting how much excellent thinking is being done by Canadians. My own excessive fondness for the work of John Ralston Saul stems from his delivery of the 1995 Massey Lectures, and my support of Michael Ignatieff’s quest for the Liberal leadership (and the subsequent eventual likelihood of Prime Ministership) comes from his 2000 Lectures (and in that case, it wasn’t so much the content of his talks, which was on human rights, but the fact that Canada deserves to have a Prime Minster who’s intelligent enough to have delivered the talks in the first place). Other past notables of the Massey Lectures include Charles Taylor (who delivered the 1991 Lectures) and Northrop Frye (in 1962; the series The Educated Imagination I consider to be essential reading).

Prior to the can-con, Noam Chomsky taught us about the media-as-propaganda model in 1988, and Dorris Lessing taught us about ‘the prisons we live inside’ in 1985. Lessing’s lectures were re-published by the House of Anansi Press last year, just in time for this year’s Nobel win to spike sales, and I picked up my copy the other day.

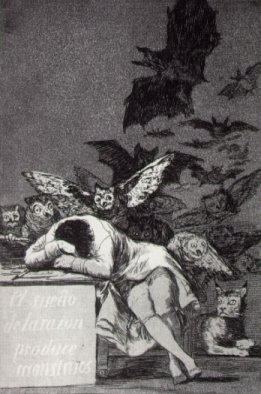

This brings me to the other side of Canadian November, and that’s the poppy. This is the impulse which contradicts our desire for knowledge (that desire to grow as individuals and as a species) and that is the desire for barbaric violence. The poppy sentimentalizes what should be considered simply shameful. How can its motto of ‘lest we forget’ still be said after 90 years of more war after that ‘war to end all wars’? It’s shame should be apparent in this embarrassment.

This year I’ve decided to boycott this emblem of remembrance, because I’m tired of war, I’ve had an ear and eyeful from the news all year and I want nothing to do with it. I don’t support the troops, I think Western governance has gone on a patriarchal war-is-glory bender and whatever threats exist are only exaggerated to promote the real agenda, which is an ancient Roman ideal of glory in death, destruction, and the vanquishing of enemies. Fuck all of that.

In her first lecture twenty-two years ago, Lessing brought up the unspoken facet of violence and war which she had witnessed in her lifetime, and that was that war was for many people fun. She opens her talks with a tale of a farmer who’s expensively imported bull had killed the boy who took care of it, and that this farmer decided to kill the bull because in his mind it had done wrong. She also tells of the post-WW II symbolic trial and ‘execution’ of a tree that had been associated with General Petain. Lessing points out that the farmer’s actions, and the villagers who destroyed a tree, were irrational, acting out of symbolism but not sense. As she says, ‘I often think about these incidents: they represent those happenings that seem to give up more meaning as time goes on. Whenever things seem to be going along quite smoothly – and I am talking about human affairs in general – then it is as if suddenly some awful primitivism surges up and people revert to barbaric behavior.’ Later, she writes: